There aren’t many things I like to write about more in my blog than little known people of the past who either made a big impact on life or were very forward thinking. Perhaps Jeremy Bentham might be my favourite though I admit I may be a little biased as I kind of count him as a friend of longstanding. Dr Johnson is up there too and I’ve written about many more.

So I was delighted to learn a little more about Charles Pearson a few days ago. Obviously I knew of him for his most famous ideas but I didn’t fully appreciate the other qualities of a man who both made a big impact on life and was very forward thinking.

Charles Pearson was born on 4th October 1793 at 25 Clement’s Lane in the City of London. He was the son of Thomas Pearson, an upholsterer and feather merchant, and his wife Sarah. After studying in Eastbourne, he was apprenticed to his father but instead studied law and qualified as a solicitor in 1816.

In 1817, he was released from his indenture by the Haberdashers’ Company and married Mary Martha Dutton. The couple had one child, Mary Dutton Pearson, born in 1820.

What I like best about Charles Pearson is that despite his comfortable upbringing and his high social status, Pearson was a radical. It’s relatively easier to be radical if you’re at the bottom of the ladder if that is your inclination.

Throughout his life Charles Pearson fought a number of campaigns on progressive and reforming issues including the removal from the Monument inscription blaming the Great Fire of London on Catholics, the abolition of packed special jury lists for political trials, and the overturning of the ban on Jews becoming stock brokers in the City.

Charles Pearson was in favour of the disestablishment of the Church of England and opposed capital punishment. Politically, he supported universal suffrage and electoral reform to balance the sizes of parliamentary constituencies. He unsuccessfully attempted to break the local monopolies developed by the gas companies, calling for the distribution pipework to be owned collectively by the consumers.

Charles Pearson was a Liberal (See Dr Alfred Salter for another forward thinking Liberal politician in south London) and was elected at the 1847 general election as a Member of Parliament for Lambeth. His campaign was prompted by a desire to promote his penal reform campaign in parliament. He resigned his seat in 1850.

He campaigned against corruption in jury selection, for penal reform, for the abolition of capital punishment, and for universal suffrage.

All of which I’m sure you’ll agree is quite something for a man of his era and background but despite all of this, we haven’t got to what perhaps his greatest legacy is particularly to London but the world at large.

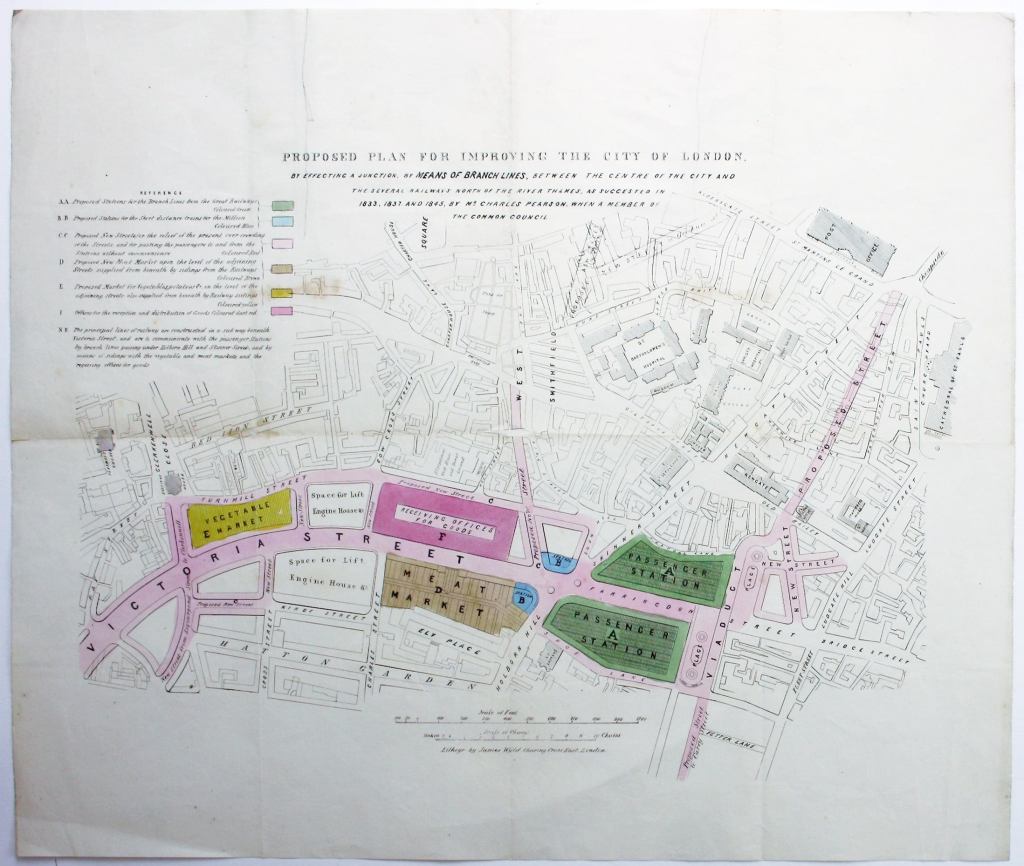

Hard as it might be to believe, congestion on the roads of London was perhaps even worse in the early to mid 19th century than two hundred years earlier. Charles recognised the increasing congestion in the City and its rapidly growing suburbs and so published a pamphlet in 1845 calling for the construction of an underground railway through the Fleet valley to Farringdon.

The proposed railway would have been an atmospheric railway with trains pushed through tunnels by compressed air. Although the proposal was ridiculed and came to nothing (and would almost certainly have failed if it had been built, due to the shortcomings of the technology proposed), Pearson continued to lobby for a variety of railway schemes throughout the 1840s and 1850s.

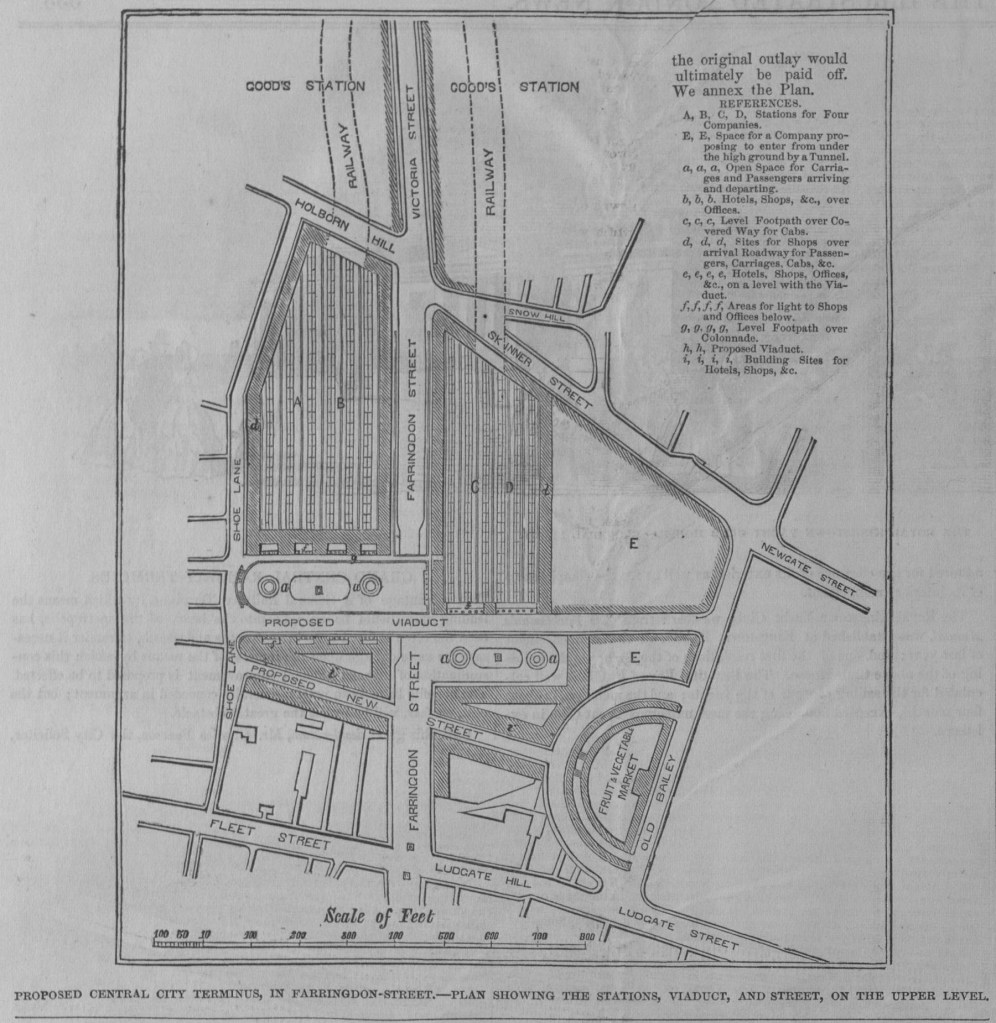

In 1846, Pearson proposed with the support of the City Corporation a central railway station for London located in Farringdon that was estimated to cost £1 million (approximately £103 million today). The station, to be shared by multiple railway companies, was to be approached from the north in a covered cutting 80 feet (24 m) wide.

Pearson’s aim in promoting this plan was to facilitate the improvement of the social conditions of City workers by enabling them to commute into London on cheap trains from new residential developments of good quality, cheap homes built outside the capital.

The 1846 Royal Commission on Metropolitan Railway Termini rejected the proposal, preferring to confirm a limit around the centre of the capital into which no new railway lines could be extended which is why even today all the biggest stations are not really in the very middle of London.

In 1854, a Select committee was set up to examine a number of new proposals for railways in London. Pearson made a proposal for a railway connecting the London Termini and presented as evidence the first survey of traffic coming into London which demonstrated the high level of congestion caused by the huge number of carts, cabs and omnibuses filling the roads. Pearson’s commentary on this was that:

the overcrowding of the city is caused, first by the natural increase in the population and area of the surrounding district; secondly, by the influx of provincial passengers by the great railways North of London, and the obstruction experienced in the streets by omnibuses and cabs coming from their distant stations, to bring the provincial travellers to and from the heart of the city. I point next to the vast increase of what I may term the migratory population, the population of the city who now oscillate between the country and the city, who leave the City of London every afternoon and return every morning.

Many of the proposed schemes were rejected, but the Commission did recommend that a railway be constructed linking the termini with the docks and the General Post Office at St. Martin’s Le Grand. A private bill for the Metropolitan Railway between Praed Street in Paddington and Farringdon received assent on 7 August 1854.

Although not a director or significant shareholder of the new company, Pearson continued to promote the project over the next few years and use his influence to help the company raise the £1 million of capital needed for the construction of the line.

He issued a pamphlet, A twenty minutes letter to the citizens of London, in favour of the Metropolitan Railway and City Station, encouraging investment and he even persuaded the City of London to invest on the basis that the railway would alleviate the City’s congestion problems.

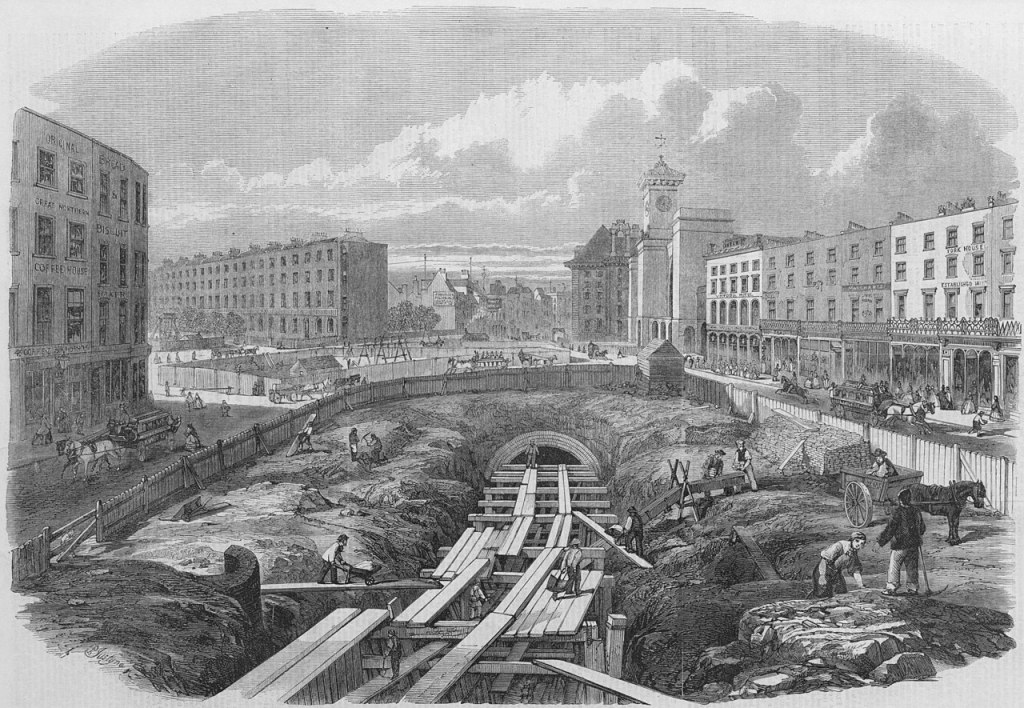

Once the railway was in operation, the City sold its shares at a profit. By 1860, the funds had been collected and the final route decided. Work on the railway started; taking less than three years to excavate through some of the worst slums of Victorian London and under some of the busiest streets.

Pearson died of dropsy on 14 September 1862 at his home at West Hill, Wandsworth, and did not live to see the opening of the Metropolitan Railway on 10 January 1863. Pearson had refused the offer of a reward from the grateful railway company, but, shortly after the railway’s opening, his widow was granted an annuity of £250 per year.

The Metropolitan Railway was a huge success and in its first year 9 million journeys were made on it. Another of Charles Pearson proposals was created to in the form of the Holborn Viaduct which could be said to be the worlds first modern flyover or overpass.

The Metropolitan Railway and the network of underground lines that grew from it was the first in the world and the idea was not adopted elsewhere until 1896 when the Budapest Metro and the Glasgow Subway were both opened.

Without Pearson’s promotion of the idea of an underground railway when he did it is possible that transport developments at the end of the 19th century developments, such as electric trams and vehicles powered by internal combustion engines, might have meant the underground solution was ignored.

The expansion of the capital that the underground network and its suburban surface extensions enabled was considerable and rapid. It helped the population of what is now Greater London to increase from 3,094,391 in 1861 to 6,226,494 in 1901 and helped fulfil the dream that Charles Pearson held that ordinary people should be able to live a better life in better conditions.

You might also like my old post 140 Facts about London Underground.

“…a better life in better conditions.” Strangely, it is still a goal.

Again, love these snippets about relatively ordinary people who punched above their weight but may not find a mention in history books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do too, someone who clearly set out to help others. It’s so rare these days. Politicians don’t even pretend to say they want people to have a better life (at least no in the U.K.) in fact my Excluded experience demonstrates they don’t. I think people like him deserve to be remembered more than many others who are. What more can you do for people then say you want the poor to have a better life in better conditions and then actually make it happen.?

LikeLiked by 1 person