There is so much to see when I go into Parliament and whilst naturally what takes the breath of many away are the grand historical chambers of the House of Lords and the House of Commons or perhaps some of the royal areas where kings and queens visit; what I always enjoy is detail of the furnishings and the art.

One of my favourite rooms is dominated by themes of war both paintings of war and old monarchs who were very successful in battle. There are two works that dominate proceedings above all else and one of these is the tremendous “THE MEETING OF WELLINGTON AND BLÜCHER AFTER THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO”

Following the destruction of the old London Houses of Parliament in a fire in 1834, much of the “Mother of Parliaments” was rebuilt and decorated in the 1850s. For the Royal Gallery, the Fine Arts Commission (led by Prince Albert) decided on a decorative scheme of 18 monumental frescos illustrating British military history. One of them “The Meeting of Wellington and Blücher after the Battle of Waterloo”, was commissioned in 1858 and the painter chosen wast Daniel Maclise (25 January 1806 – 25 April 1870).

Maclise met with difficulties when he began to reproduce the composition in its definitive form as a “fresco” in the Royal Gallery. Painting onto wet plaster, which dries quickly, he found he was unable to realise the work with as much detail as he wanted. As Maclise proposed to abandon the commission, Prince Albert persuaded him to travel to Berlin to learn a new technique called “waterglass”, which involves fixing pigments painted onto dry, porous plaster with ‘liquid glass’ (potassium silicate). After studying the technique also in Munich and Dresden, Maclise returned to London and would complete the painting in under two years.

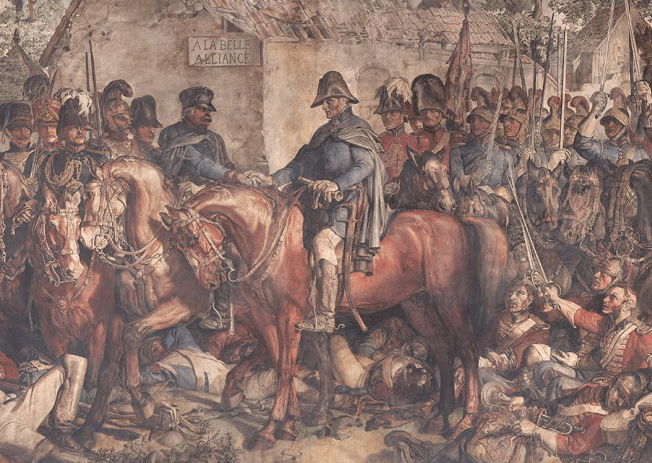

This huge painting, just over 12 feet high and 46ft 8ins long shows the Duke of Wellington meeting the Prussian Marshal Blücher in the final moments of the Battle of Waterloo, at 9.15 pm on 18 June 1815. The two heroes of the day met at the ruins of an inn called ‘La Belle Alliance’, which had been Napoleon’s headquarters during the battle. Wellington is mounted on his famous horse Copenhagen, and immediately beside him to the right are Lord Arthur Hill, General Somerset and the Hon Henry Percy, with various Life Guards and Horse Guards. Blücher is accompanied by Gneisenau, Nostitz, Blülow, and Ziethen.

On the white horse, with drawn sword at his shoulder, is an Englishman, Sir Hussey Vivian, who was attached to Blücher’s staff. All the details of this historical event were most carefully researched. It had indeed been claimed that the two generals met elsewhere in the field of battle, and rode together to the inn. The matter was settled by Queen Victoria, who wrote to her daughter Victoria in Germany, asking her to question the aged Nostitz. This old soldier, who had been Blücher’s aide-de-camp, confirmed the details of the meeting. One of the details he corrected was the question of what Blücher had worn on his head. Nostitz insisted that he wore a forage cap instead of the hat and feathers with which Maclise had provided him. The artist made the change.

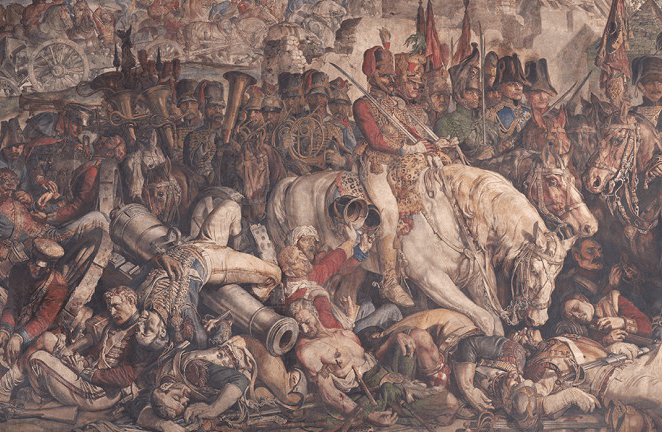

In fact the artist went to great length to speak with those who had fought and survived the battle and perhaps because of this, the prevailing mood is grim and tragic: there is no glorying in a military triumph. In the left foreground a French artillery officer lies dead across his gun, while beside him an English soldier has his leg bound and another is carried off.

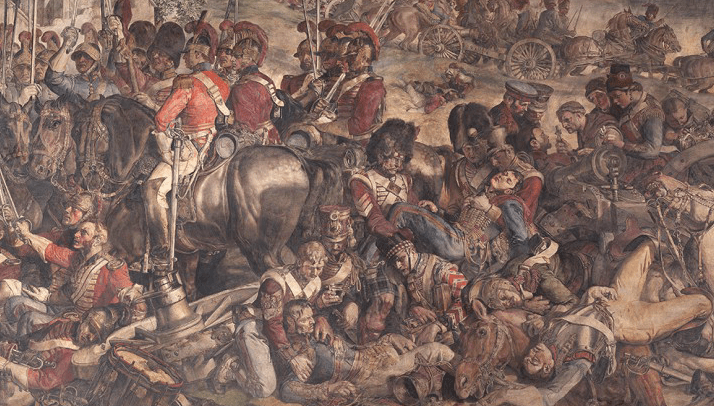

On the right foreground, a group of wounded Life Guards, whose officer lies dead against the broken-off wheel of a gun. To the right of the wheel, a wounded officer of the Lancers is tended by a doctor. Further back, a young soldier is carried away. Such is Maclise’s attention to detail that we can tell not only that this is young gallant Howard, celebrated by Byron in the poem ‘Childe Harold’, but also that the soldiers bearing him away are a Highlander, an Irish fusilier and an English Foot Guard. To the right of this group, a young Flemish officer is given the last rites by a priest.

Meanwhile in the background, the routed French flee, pursued by the Prussians, in accordance with a plan agreed between Wellington and Blücher. Pushing on through the night, they drove the French out of seven successive bivouacs, and at length drove them over the River Sambre.

The Campaign was over: the French had lost 40,000 men and almost all their artillery, while the Prussians lost 7000 and Wellington over 15,000 men. So desperate was the fighting that 45,000 killed and wounded lay on an area of about 3 square miles. At one point the 27th Inniskillens were all lying dead, still in their square, and the position of the British infantry was clear to see from the red line of their dead and wounded. It was this sombre aftermath which Maclise painted with the whole work dominated by the dead and wounded, men and horses from all regiments, emphasising the tragedy of war rather than glorifying it.

I never fail to enjoy looking at this massive, almost life-size painting. At a time when most paintings around the world were full of pomp and jubilation (indeed it’s hard to imagine even today a country like Russia or China taking such a tone) and London had every reason to do the same having beaten Napoleon, instead the grim realities of war are shown in a way that very much appeal to those in the modern day.

The Duke of Wellington was quite the ladies’ man, from what I’ve read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure there must have been no-one his equal in someways. I always like an account of when he attended some grand banquet in Paris and the hostess apologised because all the French Generals and leading figures turned their backs against him when he entered. Wellington replied to the lady not to worry as he had seen their backs before!! (on the field of battle).

LikeLike