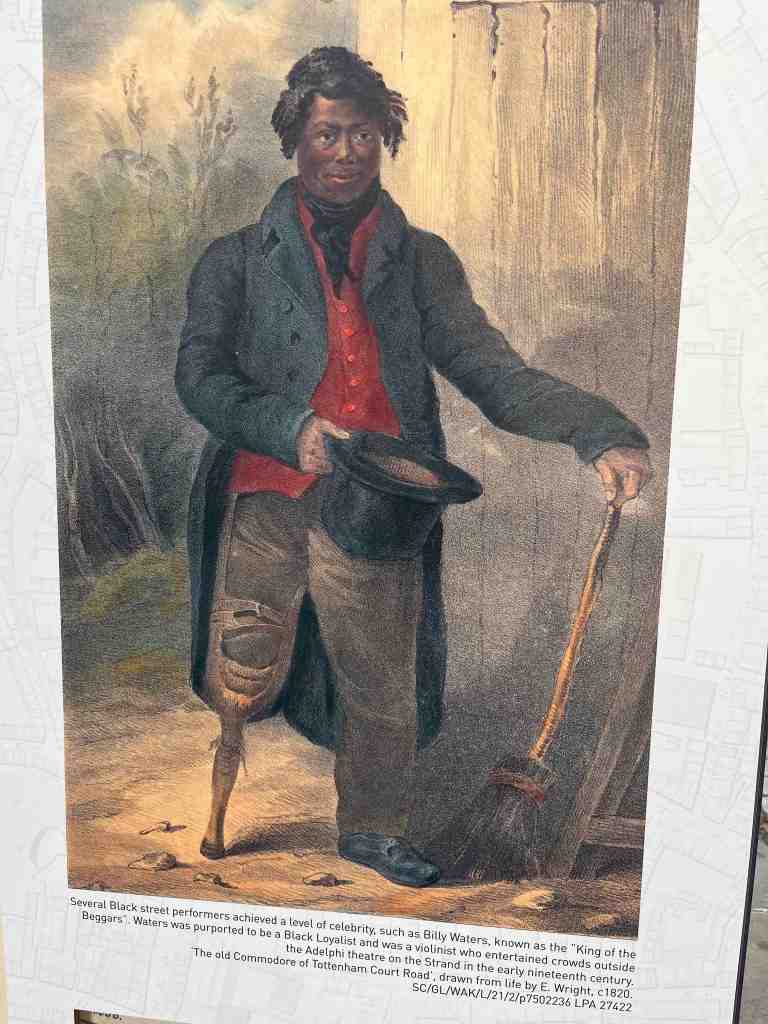

Just before I met with some tourists embarking on a London Pub Tour a few weeks ago, I caught sight of this poster near St Pauls. Part of a temporary exhibition in the yard outside. I didn’t expect to see the King of the Beggars here as he isn’t well known, obviously part of the reason he is depicted on one of the displays.

If you’re able to read the text below, the painting of the Old Commodore of Tottenham Court Road, you might see it mentioned that he is a British Loyalist. Given the time-period this would mean he was someone loyal to the Crown rather than the American Revolutionaries. Such descriptions relating to a black British person usually means though that they somehow escaped slavery and servitude.

William Waters was born in New York during the American revolution; he escaped a life of servitude by joining the Royal Navy which at that time was surprisingly to some, the largest employer of black men in the world at the time.

In 1811 he enlisted in the Royal Navy as an able seaman. At first he was on the supply-ship HMS Namur whose captain was Jane Austen’s brother Charles. Waters then joined the crew of HMS Ganymede, and was soon promoted to quarter gunner, with the rank of petty officer. The 26-gun frigate led a convoy from Portsmouth to Spain; but on the voyage home, while loosening sail aloft he slipped, and plummeted to the deck. The captain noted tersely: “Wm Waters fell from the main yard & broke both his legs, otherwise severely wounded him.” His left leg was amputated below the knee.

That might have been all but that for many people but growing up by New York’s waterfront, Billy Waters would have learned how to play fiddle and perform solo dances in dockside taverns and markets. Such agility and entertainment skills were valuable for any young sailor and they would prove vital in the years ahead.

As a wounded sailor in London he drew on them time and again to supplement a meagre pension. He’d often be spotted taking a pitch outside the Adelphi theatre on the Strand.

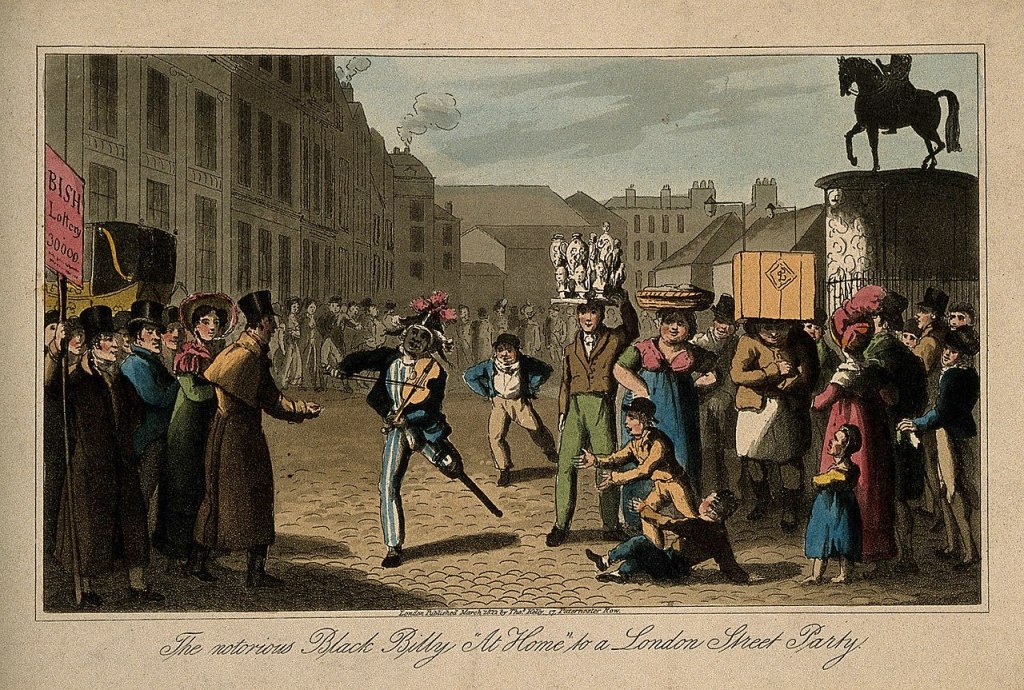

Thousands of people of all ages saw and heard Waters busking. His hallmark attire – large military-style headgear with feathers, judge’s “cauliflower” wig, tattered naval jacket – was a carnivalesque send-up of British authority at the time.

He sang and danced while fiddling and made use of his wooden leg to perform “peculiar antics” – pivoting on it, kicking it out. An engraving, “The Notorious Black Billy at Home to a London Street Party”, shows him in action flanked on one side by well-to-do citizens, on the other by children and tradespeople. A white youth mimics his steps.

Waters played for dancing, without accompaniment, and – since he needed to grab attention and be heard above street-cries and noise – his voice would be loud and penetrating, his bowing was probably rhythmic and vigorous, his touch well-accented and syncopated, his tone droning and scratchy. You can hear something similar in Sid Hemphill’s fiddling, with an echo too in Joe Thompson (1918–2012), the last traditional Black fiddler in North Carolina.

Waters embodied a spirit of lively defiance in dark times. In impoverished St Giles, nicknamed “The Holy Land” for its large Irish-Catholic population, he was a well-loved community musician. Waters and family lived in the notorious St Giles Rookery – a maze of narrow streets and courtyards with damp, dilapidated and horribly overcrowded houses, concealed passages and open sewers just a short distance from the British Museum. At night he played in a public house known as The Beggar’s Opera, the gathering-place of “cadgers”, vagrants, petty thieves, sex workers and street people.

The pub also attracted a few Regency bucks, or swells, who took delight in slumming – among them writer Pierce Egan and caricaturists George and Robert Cruikshank. In Egan’s hugely successful book Life in London, its three swell protagonists – said to be the author and the Cruikshank brothers – pay a visit to a barely disguised Beggar’s Opera. Though not named, Waters is described; and in a key illustration his profile is unmistakable. He became a famous lowlife character, ripe for further exploitation.

Life in London was swiftly adapted for the stage by William Moncrieff as Tom and Jerry, the names of the two principal swells, opening in late 1821 at the Adelphi – Waters’ pitch. In the celebrated Back Slums in the Holy Land scene, former clown Signor Paulo played the role of “Billy Waters” as a disdainful, bullying and ludicrous rogue, the leader of a group of hypocritical beggars. Tom and Jerry ran for a record-breaking 16 months.

This unearned reputation was a far cry from the real Billy Waters, who we know through only two fragments of reported speech. One comes from TL Busby, the artist who created the portrait of Billy. He wrote circa 1820: “[Billy] has a wife, and, to use his own words, ‘one fine girl, five years old’, and is not a little proud to perceive a resemblance in the child to himself.”

The other fragment is from a newspaper account of his appearance at the Sheriff’s Court of Enquiry in Hatton Garden in 1822 – the same courthouse at which the young Oliver Twist would later appear in Charles Dickens’ novel. The magistrate told Waters sternly that he should take up the offer of a room at the navy’s Greenwich hospital, and his wife would be put “in a way to provide for herself” since she wasn’t allowed to join him, adding that if he was caught begging again he would be committed. Waters, however, declared “he would live and die constant to Poll”; and that nothing but force should separate him from her.

The real Waters suffered greatly from Tom and Jerry’s defamation, losing his good name and with it his income as a busker. In later life a remorseful Moncrieff wrote that Billy attended a performance and denounced Paulo, only for the audience to turn on Waters and violently eject him. The authorities also turned on him. Two weeks after Tom and Jerry’s opening he was arrested twice on the same day, charged with “begging and collecting crowds in the streets” and “singing immodest songs”.

Even though the stage production where Waters was immortalised reaped the fruits of success, the real person behind the character continued to experience hardship. Running into further financial troubles, he was forced to carry his fiddle to the pawnbroker’s.

Given his long-lasting relationship to the musical instrument, the moment of parting with it defined the scarcity of his circumstances, rendering it impossible to continue his career as an entertainer in a last attempt to feed his family. The peg leg, which had previously saved him from arduous debtor punishments, would have met the same fate had it not been too worn out to sell.

In the end, Waters resorted to entering St Giles’s workhouse. Due to illness, he was no longer capable of undertaking any sort of employment, nor did he participate in regular workhouse duties — often entailing long hours of work as ‘payment’ for lodgings to the able-bodied. After ten days spent completely bed-bound, Waters lost the battle for his life at the age of 45.

He wasn’t forgotten however and he was commemorated in a range of pottery figures by some of the great ceramic producers of the day. Like many performers of his day, he may have been largely forgotten but those of us who are into such things will talk passionately about him. Another of the great every-day people in the history of London.

In April 2023, Billy Waters was honoured by an official blue plaque by Camden Council in Bucknell Street, in the old St Giles Rookery.

Excellent article… very interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thankyou!

LikeLiked by 1 person