For many of us, the closest we come to experiencing what Victorian poverty was like is by watching a television adaptation of a work of Charles Dickens. He would use his writing to bring about societal change in a similar way to how actors and musicians put their name to good causes today.

It can be hard for people overseas to imagine what life was like for the majority of people in the U.K. in times gone by, so used is everyone to thinking the country has always been rich and privileged when in fact it was just a tiny minority whilst most suffered every bit if not more so than those overseas.

Back then it was widely thought that poverty was as a result of a lack of a work-ethic and poor religious based morals, something that is still a popular belief in some parts of the world even today, even amongst our present government.

Of course poverty is a complicated issue and sometimes as in my own case Why has my MP and Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden left me to die? it is a result of government persecution but it could easily be due to a variety of unfortunate circumstances.

Poverty in Victorian Britain was largely seen as an impossible thing to resolve. It was too big a task, insurmountable rather like in the 1980’s it was by thought by many that people in Africa would always suffer starvation. Of course these assumptions are only the case if people won’t help and things don’t change.

More progressive people in Britain knew that things had to change and worked hard to change opinion and policy. One such person was the Rev. George Zachariah Edwards who was a vicar in Southport. He wrote ‘A Vicar As Vagrant’ which was published in 1910 and brings to us first hand his personal experience of what it was like just spending a night in one such established whilst ‘undercover in the Lancashire town of Preston..

“THE PENNY SIT UP,” PRESTON, OR, “THE HOUSE OF DESPAIR.”

The common or model lodging-house, the doss-house, or kip-house is, perhaps, the greatest source of moral contamination in our land. In the doss-house night by night, in the only living-room, the kitchen, for the whole long evening, there mix and mingle a motley throng. Honest fellows seeking work, professional beggars and thieves; prostitutes, cheap; hawkers, and gaol-birds.

They come here because, it is the only place to come to, and it is comparatively cheap— 3d, or 4d. a bed are the usual charges in the larger towns. I do not blame the doss-house keeper. He is a doss-house keeper. How can lie turn the beggar with money in his pocket away? As in every business, so in this.

Some are more honest and cleanly than others. In Preston there are at least thirty-four common lodging-houses of one description or another, twenty-three of which take in women. Some are small and need not count for much; others, with from fifty to seventy beds or more.

Preston provides, night by night, perhaps one thousand beds, not counting the casual ward in which the men and women of the road sleep. The licensed common lodging-houses are under some sort of police supervision and inspection. I do not know whether Preston is unique in one respect. I hope it is. It has a “Penny sit up.” I call it “The house of despair.” I have been there, so I speak of what I know. I went meaning to spend the night, one short night, there—short if you pass the hours of rest in refreshing sleep on a comfortable bed, but age-long if you spend it in this house of despair.

I came out with a leaden weight upon my soul that men could sink to such depths of woe, and that we, had thrust them thither. This is not a dream. This is not the wild imagination of a heated brain. It is sober, solid fact. This house of despair is to be found in Shepherd Street, Preston. Its only recommendation is its cheapness; but how dearly you buy that cheapness!

For one penny you buy the privilege of entrance—this admits you to a room about twenty-five feet long by eighteen feet broad. You enter it in the evening, when the day is done. Already there are some twenty or twenty-five men there. The room is literally bare, with nothing in it, nothing! No fireplace, no stove, no hot water pipes, no sink, no water, no beds, no chairs, no blankets, no mattresses—nothing, nothing whatever for the furnishing of the room except a small, very small oil lamp, very dimly lighted, and four long wooden kneelers about two inches off the floor sloping upwards towards the back. Two of these at either ends of the room, and the other two running right down the middle of the room back to back. What are they for? This surely is not a house of prayer? No, these are pillows, wooden pillows, and presently the floor of this room will be covered with bodies lying feet to feet in two double rows down the length of the room.

When you enter some are eating their bit of food; but remember, there is no stove, no warmth, no fire here, only a (washing) boiler in the yard, where you may get hot water. There are no cooking utensils; every man carries his own drum under his coat behind his back—just an old tin of some sort with a wire handle. When your food is eaten there is nothing to do but lie down on your length of the floor, some six feet by two feet, and then if your limbs ache with lying down on the hard boards sit up, and if you are privileged to have one of the select spots against the wall, you can lean against that if you will. If you are wet through you sit or lie in your wet rags till they dry, that is all! Think of it! Ten, twelve, fourteen hours thus. Thirty to sixty men thus, night by night, in misery, wretchedness, filth of body, and starvation. The conversation is in the dull, hopeless undertone of exhausted men, except when it flashes forth now and again. in the tone of revenge, hatred and bitterness against us who have condemned them to this. It is always heavily laden with oath or blasphemy, and is of begging, pinching, roguery, trickery, beastiality, at the best of the criminal courts, their prisoners and judges. The leaden weight of exhaustion and despair is only lifted when a man is dead drunk. And so these men try to settle themselves to sleep.

Sleep? Were human beings, God indwelt, ever meant thus to rest, in dirt, in degradation, in depression indescribable? No clean horse-box with freshly-strewn straw, this! No well-drained pig-stye with abundance of bedding, warmth and food, this! No rat-hole, this, where father, mother, and baby rats may live together and seek their meat from God! But a vermin-infested room, bare of aught but men’s bodies clad in rags—bodies which are not washed or groomed or cleaned from one twelvemonth to another, except when forced to go to casual ward or gaol. Bodies which are half-starved, emaciated, lean. Bodies which carry the germs. of horrible disease, yet which are untended, uncared for. Bodies which, because they are so poor, so poor in rich life blood, are thereby fit and proper food for the tramp’s, the dirty beggar’s worst enemy, lice. Little crawling, clinging, biting lice, which breed in twenty-four hours in the scams of your clothes next your skin, and live upon you—biting, biting, feeding, feeding, like the gnawing worm of hell. The atmosphere!

Figuratively speaking, you could cut it with a knife! You yourself sleep next to an old decrepit man, who cannot always control his bodily actions; his trousers stink, stink; you will carry the stench in your nostrils for a week. Sixty thus, and if not quite thus, all unwashed, all with the smell of the unwashed. Add to this, rank tobacco smoke of all blends, some unknown even to connoisseurs, such as “kerb-stone twist” (old chews), old cigar ends, “o.p.s.” (other people’s stumps), and old dried tea leaves. Add to this foul breath, some very foul, add also the stale atmosphere of the room itself when empty, and remember scarce any ventilation during the night except the occasional opening of the door into the yard, and you may think you imagine what you never will, till you experience it. Thus the poorest of the poor live by night in Preston, thus the local authorities allow them to live, thus we Christian men through our ignorance, our party strife, and our fear of businesslike reform suffer it, and shame on us all.

It is the cause of this great national evil of needless degradation I wish to fight; not any one result, disgusting though it be. Yet be it known in Preston that the “Penny sit up” is a Lancashire disgrace—a disgrace to the soul and spirit of man, and not a cause for pious rejoicing. My mate when stranded has gone to beg for bread to many a house in Preston, at which instead of being helped he has been told, ” Take this ticket to the Shelter in Shepherd Street; we’ve nothing to give you; we send all our broken meat to the Shelter.” Do these people know what the Shelter or the “Penny sit, up” is like? Have they ever been there? Do they know that this broken food is placed in a basket on the floor of the room and scrambled for, in a wild mad rush of angry blaspheming men?

These are facts, indisputable—and one further,—do they know that these poor men, because they have slept the night in Shepherd Street Mission Shelter, and thereby, I suppose, touched the fringe of Christian sympathy, are refused admittance in the morning to a neighbouring doss-house of no great refinement, lest their living freight gathered the night before in Shepherd Street Shelter should fall off them! This Shelter has, I believe, been open now for some few years. Doubtless the owners and instigators feel they are doing a good work for the very poor, and this makes me hesitate in saying anything; but I am convinced such a place only brings men down permanently to a lower level than the doss-house, and encourages them to stay there.

If in those years it has not been possible to put a fire in the room, to put in American cloth covered bunks like the Salvation Army have, to put forms round the room, to provide some rugs, to humanise and put a touch of home into the place, to light the place up with real Christian hope and effort—I say deliberately it would have been much better for everyone, to have closed the shelter long ago.

If Christian people can do no better than this, in God’s name let them stand back; they put to shame the living Christ; and let the children of this world, who are often wiser than the children of light, be our guides.

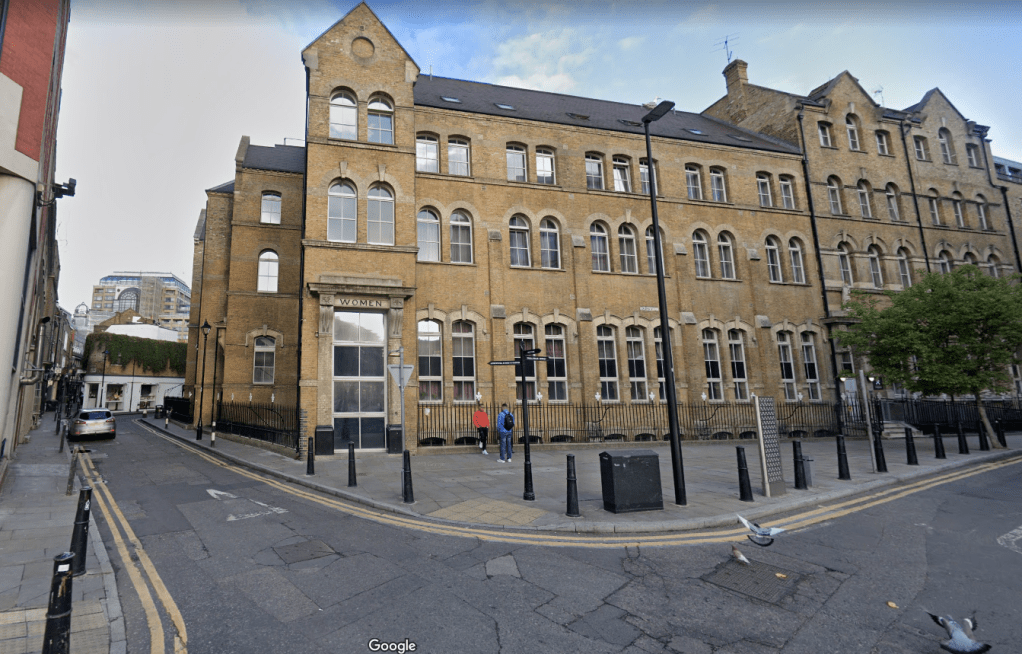

I spend quite a lot of time touching on Victorian poverty to various degrees depending on the tour I am doing on any particular day. One old doss house I go past quite often is this one in Spitalfields. As well as its own dedicated Spitalfields tour, it features on Jack The Ripper and another similar nearby is on my Great Crimes and Punishments Tour.

You can see on the photo above a throng of men and women desperately crowding round their different respective entrances in the hope of somewhere nominally safe and warm to spend a night.

The building is still going strong today and eminently recognisable from the old photo. It continued to serve the community in the social care field right up until a decade or so ago. Now it is a a Hall of Residence for students on their first year at Middlesex University.

I go past it so often and it seems like you can touch the history of the poor people who once sought refuge here, separated by just a century or so of time.

What would be the role of the rulers of the time?

LikeLike

Many of the politicians didn’t care as such destitute people were almost seen as subhuman and Queen Victoria herself was largely kept away from knowing the realities for her most poor subjects. Remarkably it was events such as Jack the Ripper and Charles Dickens that led to shock and reforms that made things change. I was wondering about your question yesterday as Britain could be said to be about the first country to properly reform and help ‘everyone’ but then in someways the poverty and hopelessness was likely the worst too. Would the first free compulsory schools or payments to older people have happened without the slums? And have countries that still don’t have true universal care not now got them because 100-150 years ago they weren’t in such a bad condition when ideas of reform spread?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always wonder when these old buildings with murky pasts are converted, if any of the energy lingers. Do present occupants ever have a sense of anything left of the past? I visited a flat at the weekend in a former asylum and fanciful me would say there was a chill in the atmosphere, but maybe that’s just because I knew of it’s former use!

And strictly tongue in cheek- a doss house to student digs. Not such a leap then? Although I know from visiting my eldest in her uni lodgings that halls of residence can be quite swish now!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes it is hard not to make a connection with student digs! I was quite shocked 2 or 3 years ago as I went to take someone one a tour meeting them at their student hall and it was more luxurious than many hotels I meet people at. 3 or 4 years of beans on toast and threadbare clothing doesn’t seem en vogue anymore! I used to live near Leavesden asylum (there are some posts on my blog) and I do remember an Arsenal footballer frequently complained about strange goings on that took place in his very fancy refurbished home in the old hospital. In the end he moved out due to the bad energy.

LikeLike

I was reading about this happening in part of the East End of London, recently, although I forget where I read it. There were three levels of ‘accommodation’ in this place: 3d got you a night in a box bunk – uncomfortable, but sleep was possible. 2d got a place at a rope strung across the room – the night could be spent leaning against this rope with your arms hanging over to keep you in place; it seems amazing that anyone might sleep for more than a few minutes at a time. 1d got you a ‘sit-up’. It was just that – some sort of wooden seat with no back and you couldn’t sleep. Anyone seen to drop off was immediately woken again. Happy days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely shocking to wake people up because in effect they hadn’t paid enough money to sleep uncomfortably leaning against a rope!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think it was a good time to be poor (when is it?).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I can say from my 2 years of being Excluded during covid that life hasn’t improved that much for the poor. Lets hope things improve in 2023.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely.

LikeLiked by 1 person