A few weeks ago I was fortunate enough to get to visit an incredible new exhibition at the British Library all about the Anglo-Saxons. Despite going past the building almost every day for 25 years, I’ve never been in it before (I avidly visited the old building) and it is one of if not the largest book repository in the world with over 150 million books and manuscripts in English, Latin and related languages. It even holds some of my books too!

Much more interesting than these though are the treasures that I went to see. The period after the Romans has long been characterised as the Dark Ages and though I personally knew this was not the case, even I was shocked at just what an educated, cultured and sophisticated lot my ancestors were.

This exhibition is here until February 2019 and houses 200 of the finest books and book-related treasures from Anglo-Saxon England. It’s not often that I get overwhelmed by history. I can only remember it happening twice, once in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo where years of pent-up enthusiasm gradually waned, hour after hour of looking at Egyptian treasures. Any one of which would be a work of such fantastic standing it would demand to be studied for hours but as part of a huge museum, eventually came just another treasure.

Similarly when visiting the WW1 cemeteries in France and Belgium and seeing hundreds of thousands of graves. All incredibly special and important and in many ways unique but when taken together, incredibly powerful and overwhelming.

This exhibition wisely restricted itself to 180 treasures covering the broad period of Anglo-Saxon England which culminated with the Norman Conquest of 1066 which was dreadful in so many ways.

Nevertheless the feeling when visiting the exhibition was one of being incredibly taken-aback, of outright wonder and amazement as well as increasingly a feeling of incredulity that anyone might have thought the Anglo-Saxons to be anything other than amongst the most enlightened of people. Obviously the Norman propaganda machine has a lot to answer for but the fight back starts here!

Photos aren’t allowed in the exhibition so here are just some of the treasures which you can see and whose photos are available in the public domain.

In the photo above you have The Alfred Jewel. It is an æstel which is inlaid enamel with gold and depicts King Alfred The Great. Alfred is the only king denoted as being ‘Great’ and was a great believer in ‘books’ and education for the common people. An æstel is a long rod with which you might point at the text of a book such as The Holy Bible to avoid touching the script. Similar to a Yad which Jewish people use when reading The Torah.

The piece dates to about 880AD and was found in a Somerset field in 1693. As well as being a great man of words, King Alfred was a man of action and was pivotal in finally freeing our lands from the Vikings.

This item also gives me an unexpected chance to link to my post on the letter æ

This ceramic item is known as The Spong Man. It was found in Norfolk in the largest Anglo-Saxon cemetery yet unearthed and dates from the 6th Century. It is 14cm in height (about 5.5 inches) and is actually the top of a large ceramic urn. One can spend forever contemplating what it is the character is thinking about. These days we have simple corks or screw lids but those wrongly labelled as being in the Dark Ages had these instead.

What makes it even more interesting is that it highlights how people of the time were happy to cremate their dead which earlier Roman Christians clearly were against and demonstrates the new ideas of our Jute, Angles and Saxons forebears; originally brought in by the Romans in the 3rd century to strengthen defences and yet like many other places, gradually took over their new homes… one way or the other.

The incredible item above is a gold belt-buckle, found in the famous Sutton Hoo hoard in Suffolk in the 1930s. Its beautiful and ornate decorations can’t be truly appreciated unless seen in person.

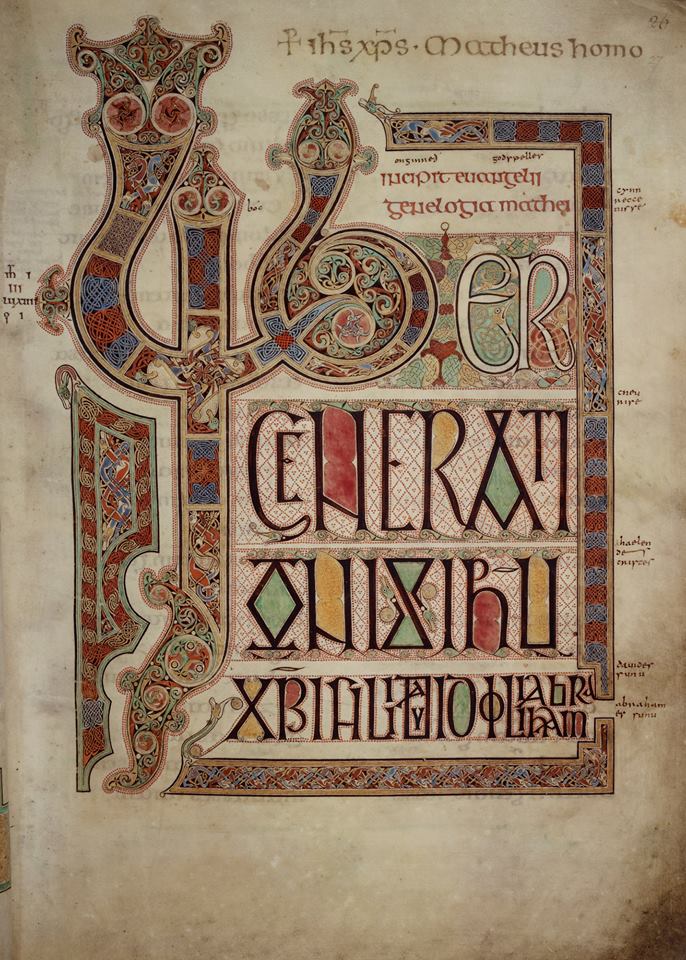

The Illuminated Manuscripts were the one thing I was hoping to see. They are from the island of Lindisfarne or Hply Island, just off the coast of Northumberland near the Scottish border and were a long-time hotbed for early Christians until famously being the scene of the very first Viking attack.

The manuscript is breathtakingly beautiful and I could have spent all day looking at it. Apart from its intrinsic value as a remarkable survival of an ancient and astonishingly beautiful work of art, the manuscript displays a unique combination of artistic styles that reflects a crucial period in England’s history.

Christianity first came to Britain under the Romans, but subsequent waves of invasion by non-Christian Saxons, Angles, and Vikings drove the faith to the fringes of the British Isles. The country was gradually re-converted from 597, after St Augustine arrived from Rome to convert the pagan ‘Angles into angels’.

Religious differences between the indigenous ‘Celtic’ Church and the new ‘Roman’ Church were settled at the Synod of Whitby in 664. In the manuscript, native Celtic and Anglo-Saxon elements blend with Roman, Coptic and Eastern traditions to create a sublimely unified artistic vision of the cultural melting pot of Northumbria in the seventh and eighth centuries.

The Lindisfarne Gospels, and others like it, helped define the growing sense of ‘Englishness’ which was strong enough to survive the Norman Conquest of 1066 and forge the nation that exists today.

The Domesday Book, often known as the Doomsday Book is one of the most famous books in the world. It is a complete record from 1086 that William The Conqueror used to catalogue everything the two-thirds of England that he had firm control over. Of course it is a Norman book but the reason it is here is that England was the only country sophisticated enough to have an administration to keep such incredible details and the administration was an aspect Anglo-Saxon civilisation, again showing how wrong it is to label these people as somehow backwards or ignorant. There are still countries in the world today that don’t have such accurate records and this book is 950 years old.

The Domesday book is a treasure for historians but also gives some insight as to why England was such a desirable target for invasion for more than a millennia as well as indicating that as our reputation today still says, we are sticklers for doing things properly and by the book!

Written in the monastic scriptorium in the 7th Century, the Codex Amiatinus was one of three single volume Bibles made at Wearmouth-Jarrow.

Made by monks under the direction of Abbot Ceolfrith, they started the project in AD692.

The oldest complete Latin Bible in existence, it was rare to make a single volume Bible as they usually contained a small number of books like the four gospels.

“It is one of the most important copies of the Bible in the world and one of the most important manuscripts made in the British Isles and associated with Venerable Bede and Wearmouth-Jarrow.

“Bible means library and the Codex Amiatinus was making a statement. Three copies of the Codex Amiatinus were produced in Latin calligraphy at the monastery.

Two stayed at Wearmouth and Jarrow and in AD716, the third left for Rome with Abbot Ceolfrith and his followers where it was intended to be given to Pope Gregory II as a gift.

Abbot Ceolfrith died on route in France, but his dream was fulfilled and the book was taken by some of his followers on to Rome.

Some years later, it was rediscovered in the monastery of San Salvatore in Italy before being moved to the Laurential Library in Florence where it can be found today.

The other two copies have been lost and for a millennia it was assumed that due to the fabulous sophistication and beauty of the book that it had to be Italian. Then in the 19th century it was found out the dedication page had been altered and it was in fact from Northumbria. It was a conscious effort to show the world that whatever Rome could do, Northumbria could do it bigger and better.

The Codex Amiatinus weighs more than 34kg (75lbs) and each page is made from vellum which would have came from hundreds of calf hides.

You might remember in July when I went to walk Hadrians Wall that I visited the wonderful St Pauls Monastery in Jarrow, home of the oldest stained glass window in the world and home of amongst many other people, the famous Venerable Bede. Bede is no doubt behind the Codex Amiatinus and I never dreamed that I would ever see not just one but several of his great and ancient works.

Well, I’ve gone 6 years with this blog and only mentioned the Venerable Bede sparingly and here I am mentioning him twice in the same post. I’m sure that someone, somewhere has a whole blog on Bede. This book is another incredibly valuable treasure and was completed in 731 AD. The work tells the story of the conversion of the English people to Christianity.

Bede’s account is the chief source of information about English history from the arrival of St Augustine in Kent in 597 until 731. But Bede begins his history much earlier, with Julius Caesar’s invasion of England in 55 BCE. Bede used several other sources in compiling his own account, each of which he acknowledged.

After briefly summarising Christianity in Roman Britain, Bede describes St Augustine’s mission, which brought Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons. The work describes the subsequent attempts to convert the different kingdoms of Britain, including Mercia, Sussex and Northumbria.

Bede (b. c. 672, d. 735) was born in Northumbria, and at the age of seven entered the monastery of Wearmouth and Jarrow near Newcastle, where he spent all of his adult life. He was also famous for the works he wrote on the interpretation of Scripture, on the natural world and on how to calculate the date of Easter.

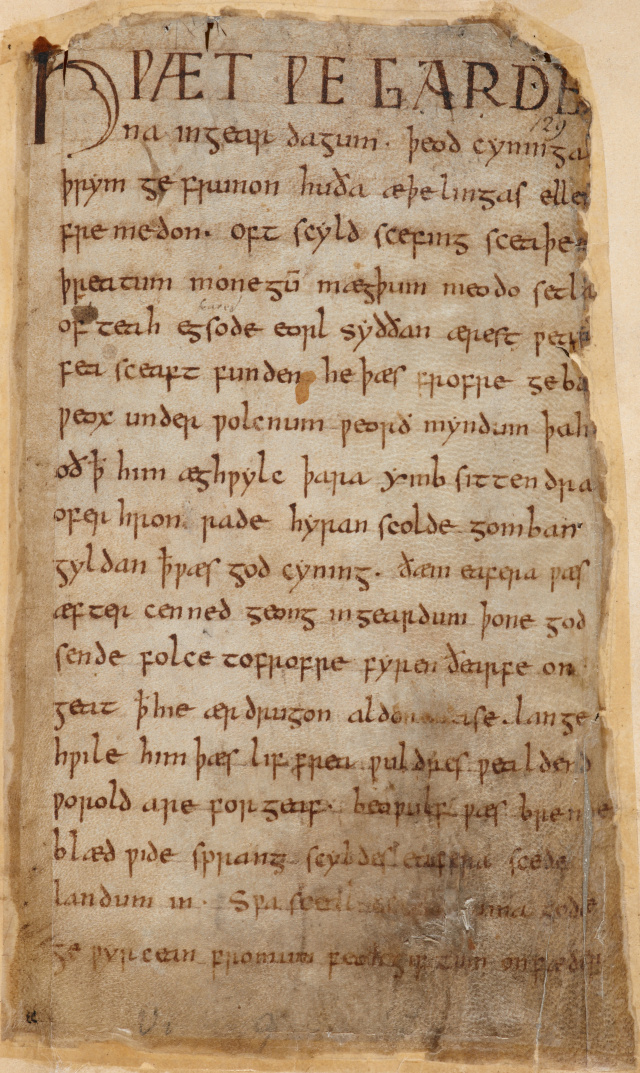

Before I end up writing a guide to the entire collection, I will finish with the epic of Beowulf. It is said by many to be the oldest story in the English language. It is certainly the longest epic poem in Old English, the language spoken in Anglo-Saxon England before the Norman Conquest. More than 3,000 lines long, Beowulf relates the exploits of its eponymous hero, and his successive battles with a monster named Grendel, with Grendel’s revengeful mother, and with a dragon which was guarding a hoard of treasure.

Beowulf survives in a single medieval manuscript. The manuscript bears no date, and so its age has to be calculated by analysing the scribes’ handwriting. Some scholars have suggested that the manuscript was made at the end of the 10th century, others in the early decades of the 11th, perhaps as late as the reign of King Cnut, who ruled England from 1016 until 1035.

Nobody knows for certain when the poem was first composed but it seems this copy is at least 1,000 years old.

One of the wonderful things about this exhibition was being able to see the incredible books on which our civilisation is based upon and spend time reading, if not usually comprehending the texts upon the pages. Certainly even if you can’t read Latin (which I can’t) or aren’t very good at working out Old English (which I am if I can read the writing), then you can still appreciate the beauty and magnificence of the books and the other treasures.

I will definitely have to revisit the exhibition again before it closes in February for it was too much to take in and appreciate. I’m ever so glad and surprised to have the opportunity to have seen these great objects once but I don’t think to see them twice in a life-time would be overkill.

I hope you enjoyed this rather special blog-post and might encourage people to see the Anglo-Saxons lived in anything but the Dark Ages.

What a excellent post! The Codex Aminatius is so huge and your photo gives it real scale.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it must have been an incredible achievement to create such a book. It also helps you appreciate how special books really are and the next stage of development with the printing press that allowed us all to own smaller books!

LikeLiked by 1 person

When we are in the presence of such books history is compressed to our own eye blink. How wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person