Nellie Duncan was born in Callander, near Stirling, in 1897, and as a child claimed the magical ability called “second sight”. She dallied with the supernatural from a young age and upon becoming an unmarried mother at 17, she was disowned by her parents, and found unpleasant work in a jute mill.

In 1916 she married a cabinetmaker, Henry Duncan – but, trapped by poverty and overwork, the couple fell chronically ill. Soon they had eight children – contraception was considered sinful – and a mountain of debt.

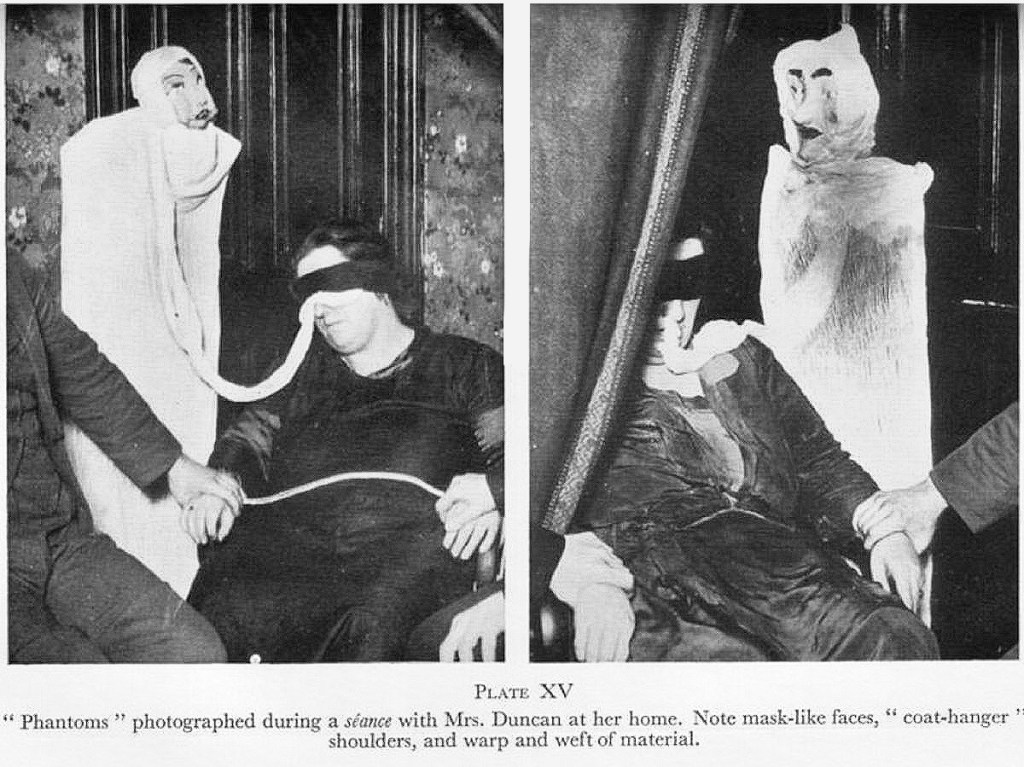

Nellie Duncan took in washing as well as labouring in a bleaching plant, and in spite of all their troubles, she claimed joyful contact with God and the afterlife. As she fell into apparent trances, ghostly spirits would speak through her lips. She and Henry set up a darkened séance room where white gloop – “ectoplasm” – appeared before paying visitors, flowing out of Nellie’s mouth and nose to manifest spirits’ bodies. Cynics might have believed the ectoplasm looked rather like muslin cloth, but her customers loved it.

In 1930, Duncan went to Edinburgh and London for appointments with psychic investigators. They tested her mediumship, strip-searching, photographing and X-raying her. Some observers confirmed her claims, although celebrity investigator Harry Price accused her of regurgitating muslin to fake materialisations. Nonetheless, her efforts paid off. Being accepted by the London Spiritualists’ Alliance meant the opportunity to go on séance tours of Britain, bringing fame and wealth.

Jumping forward to the Second World War and it’s the 25th November 1941. Off the Egyptian coast, HMS Barham explodes after a U-boat torpedo strike and sinks within minutes; sadly over 800 Navy men are killed almost simultaneously. All news of the sinking is censored. Yet, in Barham’s home port, Portsmouth, the sailors’ families soon hear rumours; and visitors to the séances of Helen Duncan, a spiritualist medium, apparently witness a miracle. Nellie spoke with the ghost of a Barham sailor, and revealed the ship’s loss. Nellie in effect makes the news of the sinking public long before the official announcement of the sinking.

In January 1944, Nellie Duncan was booked for a repeat visit to Portsmouth, to give materialisation séances. In this blacked-out, bombed naval city, many had lost loved ones, and Duncan offered news from the beyond, or even hope that those missing in action had survived. At one séance, the mother of missing RAF navigator Freddie Nuttall was told that he had been shot. Yet an enquiry at a further séance produced contradictory news: while his aircraft’s pilot, Robert Pinkerton, had died, Freddie was “living round about France, and someone is caring for him”.

Today we know that Nuttall and Pinkerton had both been killed when their plane exploded on the 23rd June 1943.

Following complaints of distasteful speculation about war casualties, the police raided Duncan’s séance. She and the organisers were initially charged under the Vagrancy Act, used to prosecute travelling fortunetellers, but on 8th February , prosecutors substituted more serious allegations under the Witchcraft Act 1735. “Through the agency of the said Duncan, spirits of deceased persons appeared to be present,” the charges stated, “communicating with living persons.”

That made Nellie Duncan potentially guilty of conspiracy with séance organisers to “pretend to exercise or use a kind of conjuration” (“conjuration” meaning the summoning of spirits). The 1735 Act was aimed at people who charged fees for fraudulent divination, healing or treasure-hunting, not at the supposed practice of those magical acts – but because it was titled the “Witchcraft Act”, journalists labelled Nellie Duncan a witch.

Her defence was led by Charles Loseby, a passionate spiritualist. To keep Duncan and her co-defendants out of jail, another barrister might have argued that his client’s beliefs were unusual but sincere. Besides, Duncan’s séances contained nothing like “conjuration”: no spells or rites were chanted, no demons were being raised. But instead Charles Loseby chose a disastrous strategy: he claimed that everything spiritualists believed was literally true. There was no death, he claimed: spirits – human and animal souls – lived on into another world, and could speak with the living through the bodies of mediums. He produced over 40 witnesses who agreed.

Yet although he believed that Duncan possessed near-messianic abilities, Charles treated her with disrespect: “a kind of conduit-pipe” for ghosts, “a big fat woman”, “uninspired”, “a nobody”, unable to “speak in cultured English”. The jury should reject evidence of fraud, he argued, because “it involves deep thinking on the part of Mrs Duncan, which you may think is totally and absolutely ridiculous”. In fact her legal team ensure that Nellie Duncan was not allowed to speak in her own defence.

The case for the defence got even worse with Charles Loseby accidentally revealing that his client was a repeat offender. In 1933, she had been convicted of fraud in Edinburgh for representing spirits with a stuffed vest masquerading as ectoplasm, and attacking her critics with a chair, shouting “foul and blasphemous language”.

The trial ended on the 31st March 1944 when the prosecution and defence concluded their cases, the jury took just 25 minutes to find Duncan and her co-defendants guilty. Sobbing “I have done nothing… it’s all lies”, she was sent to prison for nine months; she would serve six.

Nellie Duncan was the final person to receive a prison sentence in Britain under the Witchcraft Act. Campaigning for her release, even her spiritualist backers labelled her Britain’s “last witch”, because they thought her the victim of a witch trial, a travesty of justice. Certainly, the magical language used to describe her – “conjuration”, “blasphemous”, “curses” – recalled the witch hunts of another era.

Released in 1945, Nellie Duncan continued to conduct séances until her death at the age of 59 in 1956.

Historians today know not only the truth about Freddie Nuttall and Robert Pinkerton, but also that HMS Barham’s loss took two months to be announced officially to the public, giving Duncan plenty of time to hear rumours of the sinking. Winston Churchill, then prime minister, described the choice to hold a Witchcraft Act trial in 1944 as “obsolete tomfoolery”. Yet framing Duncan’s court appearance as a witch trial worked for prosecutors, defenders and journalists, because it made a great story. The ancient date of the Witchcraft Act presented mediumship as a historical throwback, with Duncan as “a ridiculous person, a kind of witch – we all dislike witches” (in Charles Loseby’s words).

Nellie was the final person to receive a prison sentence in Britain under the Witchcraft Act. Campaigning for her release, even her spiritualist backers labelled her Britain’s “last witch”, because they thought her the victim of a witch trial, a travesty of justice. Certainly, the magical language used to describe her – “conjuration”, “blasphemous”, “curses” – recalled the witch hunts of another era and one that hopefully in the U.K. at least, is firmly in our past.

The Witchcraft Act was repealed in 1951 by the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951 and despite a number of attempts, Nellie Duncan has not been post-hostumously pardoned of her conviction.