As we near the end of the tumultuous tale, a few people have been asking me about the title of this series. It actually comes from an old Treasure Island film and is uttered by actor John Newton as Long John Silver. It is said that all our popular opinions and indeed impressions of pirates come from his portrayal. Arrgh, that be true my lad. Shiver me timbers and on with the show.

The surviving mutineers on the Speedwell had an anxious time before eventually securing passage to Rio de Janeiro on the brigantine Saint Catherine, which set sail on the 28th March 1742. Once in Rio, internal and external diplomatic wrangling continually threatened to terminally complicate either their lives, or at least their return to England. King did not help the situation, having formed a violent gang that repeatedly terrorised his former shipmates on various pretexts, causing them to move to the opposite side of the city to avoid King. After many episodes of fleeing their accommodations, Bulkley, Cummins and the cooper, John Young, eventually sought protection from Portuguese authorities.

Captain Stanley Walter Croucher Pack describes these events:”As soon as the ruffians had gone [King’s gang], the terrified occupants left their house via the back wall and fled into the country. Early the next morning they called on the consul and asked for protection. He readily understood that they were all in mortal peril from the mad designs of the boatswain [King] and placed them under protection and undertook to get them on board a ship where they could work their passage.”

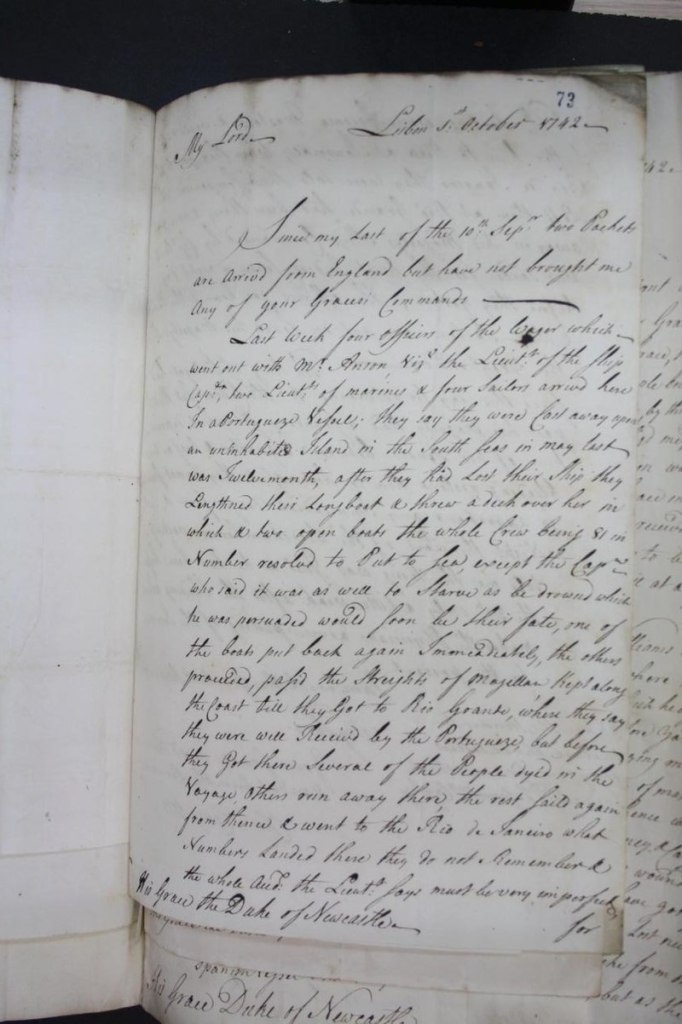

The mutineers eventually secured passage to Bahia aboard the Saint Tubes, which set sail on 20 May 1742. They gladly left King behind to continue causing criminal havoc in Rio. On 11 September 1742, Saint Tubes left Bahia bound for Lisbon, and from there they embarked in HMS Stirling Castle on 20 December bound for Spithead, England. They arrived on New Year’s Day 1743, after an absence of more than two years. Events were also reported back to London from the British consul in Lisbon, in a dispatch dated 1st October 1742.

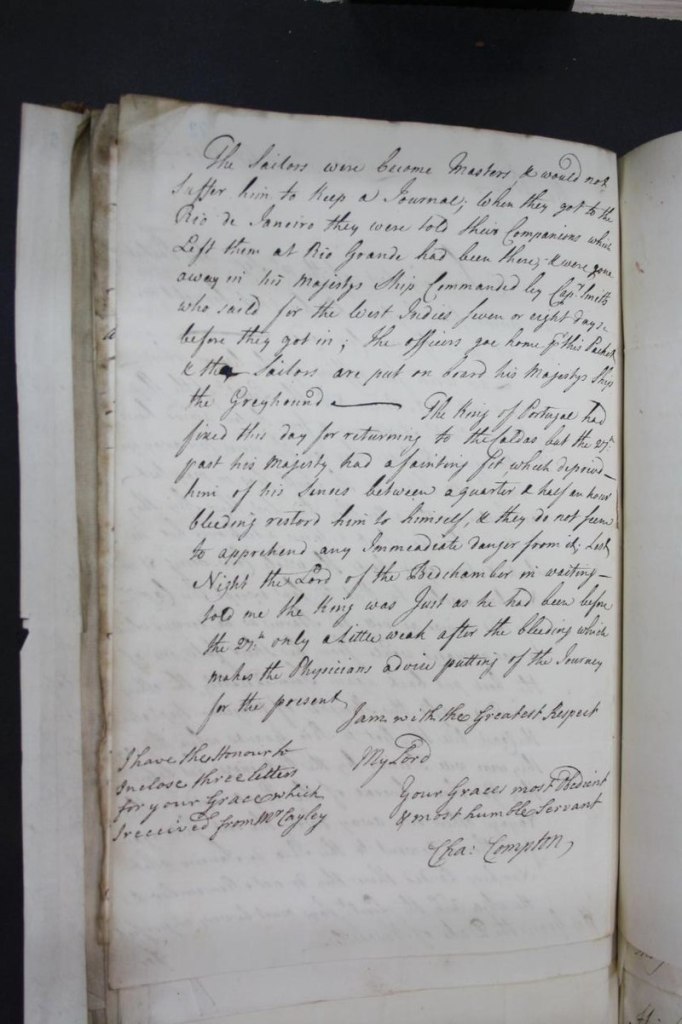

“Last week four officers of the Wager which went out with Mr Anson, viz the Lieutenant of the ship [illegible, Bulkley?], two lieutenants of marines and four sailors arrived here in a Portuguese vessel; they say they were cast away upon an uninhabited island in the South Seas in May last twelvemonth, after they had lost their ship they lengthened their longboat and threw a deck over her in which & two open boats the whole crew being 81 in number resorted to put to sea, except their Captain who said it was as well to starve as be drowned which he was persuaded would be their fate [this is a lie]. One of the boats put back again immediately [the barge], the others proceeded, sailed the Straights of Magellan, kept along the coast ’till they got to Rio Grande, where they say they were well received by the Portuguese. But before they got there several of the people died in the voyage, others ran away there [meaning Isaac Morris and others, this is also a lie]. The rest sailed again from thence and went to Rio de Janeiro, what numbers landed there they do not remember. The whole event the Lieutenant [Baynes] says must be very important for the sailors were become masters and would not suffer him to keep a journal. When they got to the Rio de Janeiro there were lots of their companions who left them at Rio Grande had been there & were gone away in His Majesty’s ship commanded by Captain Smith who sailed for the West Indies seven or eight days before they got in. The officers gone home of this Packet [HMS Stirling Castle] & the sailors are put on board His Majesty’s ship the Greyhound.”

Stanley Walter Croucher Pack’s book describes a similar report:”Arrival of some of the castaways from the loss of H.M.S. Wager in the South Pacific. Were well treated by Portuguese at Rio de Janeiro, but sailors were mutinous against their officers. King of Portugal has had another seizure and his departure for Caldas is postponed… etc.”[

Lieutenant Baynes rushed ahead of Bulkley and Cummins to the Admiralty and gave an account of what happened to Wager, which reflected badly on Bulkley and Cummins but not himself. Baynes was a weak man and an incompetent officer, as was recorded by all those who provided a narrative of the shipwreck and mutiny. As a result of Baynes’ report, Bulkley and Cummins were detained aboard Stirling Castle for two weeks whilst the Admiralty decided how to act. It was eventually decided to release them and defer any formal court martial proceedings until the return of either Anson or Cheap. When Anson did return in 1744, it was decided that no trial would proceed until Cheap returned. Bulkley asked the Admiralty for permission to publish his journal; it responded that it was his business and he could do as he liked. Bulkley released a book containing his journal, but the initial reaction from some was that he should be hanged as a mutineer.

John Bulkley found employment when he assumed command of a forty-gun privateer Saphire. It was not long before his competence and nerve found him success as he tricked his way around a superior force of French frigates which his vessel encountered when cruising. As a result, Bulkley’s exploits were reported in popular London papers and gained him some celebrity. He began thinking that it would not be long before the Admiralty would offer him the coveted command of a Royal Navy ship. However there was one last twist in a terrible tale for him as on the 9th April 1745, Captain David Cheap arrived back in England.

How Captain Cheap returned home with his other surviving stragglers is an epic tale in itself.

By January 1742 (January 1743 in modern calendar, the year changed on 25 March in those days), as Bulkley was returning to Spithead, the four survivors of Cheap’s group had spent seven months in Chacao. Nominal prisoners of the local governor, they were allowed to live with local hosts and were left unmolested. John Byron faced an additional hurdle in his efforts to return to England began with the old lady who initially looked after him (and her two daughters) in the countryside before his move to the town itself. All of the ladies were fond of Byron and became extremely reluctant to let him leave, successfully getting the governor to agree to Byron staying with her for a few extra weeks. He finally left, amidst many tears. Once in Chacao, Byron was also offered the hand in marriage of the richest heiress in the town. Her beau said, although “her person was good, she could not be called a regular beauty”, and this seems to have sealed her fate. On 2 January 1743, the group left on a ship bound for Valparaíso. Cheap and Hamilton removed to Santiago, as they were officers who had preserved their commissions; Byron and Campbell were unceremoniously jailed.

Byron and Campbell were confined in a single cell infested with insects and placed on a starvation diet. Many locals visited their cell, paying officials for the privilege of looking at the ‘terrible Englishmen’, people they had heard much about, but never seen before. However, the harsh conditions moved not only their curious visitors but also the sentry at their cell door, who allowed food and money to be taken to them. Eventually Cheap’s whole group made it to Santiago, where things were much better. They stayed there on parole for the rest of 1743 and 1744. Exactly why becomes clearer in Campbell’s account:”The Spaniards are very proud, and dress extremely gay; particularly the women, who spend a great deal of money upon their persons and houses. They are a good sort of people, and very courteous to strangers. Their women are also fond of gentlemen from other countries, and of other nations.”

After two years, the group were offered passage on a ship to Spain; all agreed, except Campbell. He chose to travel overland with some Spanish naval officers to Buenos Aires and from there to connect to a different ship also bound for Spain. Campbell deeply resented Cheap’s giving him less money in a cash allowance than he gave to Hamilton and Byron.[ Campbell was suspected to be edging toward marrying a Spanish colonial woman, which was against the rules of the Royal Navy at that time. Campbell was furious at this treatment. He wrote:”…the misunderstanding between me and the Captain, as already related, and since which we had not conversed together, induced me not to go home in the same ship with a man who had used me so ill; but rather to embark in a Spanish man-of-war then lying at Buenos Aires.”

On the 20th December 1744, Cheap, Hamilton and Byron embarked on the French ship Lys] which had to return to Valparaiso after springing a leak. On 1st March 1744 (which 1745 in the modern calendar) Lys set out for Europe, and after a good passage round the Horn she dropped anchor in Tobago in late June 1745. After managing to get lost and sail obliviously by night through the very dangerous island chain between Grenada and St Vincent, the ship headed for Puerto Rico. The crew was alarmed at seeing abandoned barrels from British warships, as Britain was now at war with France. After narrowly avoiding being captured off San Domingo, the ship made her way to Brest, arriving on 31st October 1744. After six months in Brest being virtually abandoned with no money, shelter, food or clothing, the destitute group embarked for England on a Dutch ship. Finally on the 9th April 1745 they landed at Dover, three men of the twenty who had left in the barge with Cheap on 15th December 1741.

News of their arrival quickly reached the Admiralty, and John Bulkley. Cheap went directly to London with his version of events. A court martial was organised, with John Bulkley being at risk of execution.

There was one other group of hardy survivors who made there way back home against the odds.

Left by Bulkley at Freshwater Bay, in the place where today stands the resort city of Mar del Plata,were eight men who were alone, starving, sickly and in a hostile and remote country. After a month of living on sea lions killed with stones to preserve ball and powder, the group began the 300-mile trek north to Buenos Aires. Their greatest fear were the Tehuelche nomads, who were known to transit through the region. After a 60-mile trek north in two days, they were forced to return to Freshwater Bay because of the lack of water resources. Once back they decided to wait for the wet season before making another attempt. They became more settled at the bay, built a hut, tamed some puppies they took from a wild dog, and began raising pigs. One of the party spotted what they described as a ‘tiger’ reconnoitering their hut one night. Another sighting of a ‘lion’ shortly after this had the men hastily planning another attempt to walk to Buenos Aires (they actually saw a jaguar and a cougar).

One day, when most of the men were out hunting, the group returned to find the two left behind to mind the camp had been murdered, the hut torn down, and all their possessions taken. Two other men who were hunting in another area disappeared, and their dogs made their way back to the devastated camp. The four remaining men left Freshwater Bay for Buenos Aires, accompanied by sixteen dogs and two pigs.

The party eventually reached the mouth of the River Plate, but, unable to negotiate the marshes on the shores of Samborombon Bay, they were forced to make their way back to Freshwater Bay. Shortly afterwards a large group of Tehuelches on horseback surrounded them, took them all prisoner, and enslaved them. After being bought and sold four times, they were eventually taken before Cangapol, a chieftain who led a loose confederation of nomad tribes dwelling between the rivers Negro and Lujan. When he learned they were English and at war with the Spanish, he treated them better. By the end of 1743, after eight months as slaves, they eventually told the chief that they wanted to return to Buenos Aires. Cangapol agreed but refused to give up John Duck, who was of mixed race origin or a mulatto as the term was then. An English trader in Montevideo, upon hearing of their plight, put up the ransom of $270 for the other three and they were released.

If all of this wasn’t bad enough, upon their arrival in Buenos Aires, the Spanish governor put the party in jail after they refused to convert to Catholicism. I n early 1745 they were moved to the ship Asia, where they were to work as prisoners of war. After this they were thrown in prison again, chained, and placed on a bread and water diet for fourteen weeks, before a judge eventually ordered their release. Then Alexander Campbell, another of Wager‘s crew, arrived in town.

On the 20th January 1745 Campbell and four Spanish naval officers set out across South America from Valparaiso to Buenos Aires. Using mules, the party trekked into the high Andes, where they faced precipitous mountains, severe cold and, at times, serious altitude sickness. First a mule slipped on an exposed path and was dashed onto rocks far below, then two mules froze to death on a particularly horrendous night of blizzards, and an additional twenty died of thirst or starvation on the remaining journey. After seven weeks travelling, the party eventually arrived in Buenos Aires.

It took five months for Campbell to get out of Buenos Aires, where he was twice confined in a fort for periods of several weeks. Eventually the governor sent him to Montevideo, which was just 100 miles across the River Plate. It was here that the three Freshwater Bay survivors, Midshipman Isaac Morris, Seaman Samuel Cooper and John Andrews were languishing as prisoners of war aboard Asia, along with sixteen other English sailors from another ship. While his fellow shipmates were treated harshly and confined aboard Asia, Campbell, who had voluntarily converted to Catholicism, wined and dined with various captains on the social circuit of Montevideo.

All four Wager survivors departed for Spain aboard Asia at the end of October 1745, but the passage was not without incident as I’m sure no-one who has read all of this would have expected anything less. Having been at sea three days, eleven Indian crew on board mutinied against their barbaric treatment by the Spanish officers. They killed twenty Spaniards and wounded another twenty before briefly taking control of the ship (which had a total crew of over five hundred). Eventually the Spaniards worked to reassert control and through a ‘lucky shot’, according to Morris, they killed the Indian chief Orellana. His followers all jumped overboard rather than submit to Spanish retribution.

Asia dropped anchor at the port Corcubion, near Cape Finisterre, on 20 January 1746. The authorities chained together Morris, Cooper and Andrews and put them in jail. Campbell went to Madrid for questioning. After four months held captive in awful conditions, the three Freshwater Bay survivors were eventually released to Portugal, from where they sailed for England, arriving in London on 5 July 1746. Bulkley had to confront men he assumed had died on a desolate coastline thousands of miles away.

Campbell’s insistence that he had not entered the service of the Spanish Navy, as Cheap and Byron had believed, was apparently confirmed when he arrived in London during early May 1746, shortly after Cheap. Campbell went straight to the Admiralty, where he was promptly dismissed from the service for his change in religion. His hatred for Cheap had, if anything, intensified. After all he had been through, he completes his account of this incredible story thus:”Most of the hardships I suffered in following the fortunes of Captain Cheap were the consequence of my voluntary attachment to that gentleman. In reward for this the Captain has approved himself the greatest Enemy I have in the world. His ungenerous Usage of me forced me to quit his Company, and embark for Europe in a Spanish ship rather than a French one.

There is one last post to go on this seemingly unparalleled tale and in that we will see what happened with the Court Martial hearing and the aftermath of the Wager Mutiny.