Jeremthy Bentham is a famous 18th and 19th century political philospher. Unlike many before and since, you can actually visit Jeremy today as he had himself preserved so he could be wheeled out at dinner parties in case his friends missed him.

You might never have heard of Jeremy Bentham but I guarantee you’ll find him to be a fascinating character who was centuries ahead of his time. It should be noted that the post does include a photo of his preserved head. It’s not terribly bad and at least you don’t have to smell it but it is still at the end of a day, a preserved and severed 250 year old head.

I’ve been going past the home of Jeremy for about 25 years now and never before found the time to pop in and say hi. I’ve seen a few dead people before, the most famous being Egyptian Pharoah Ramses II who famously fought with Moses and defied God. There aren’t many people from The Bible that you can meet except perhaps the head of John The Baptist but there are several heads scattered around the Middle East and Europe so it’s hard to be sure which is the authentic head.

One day I am sure I will go and see Lenin when I get round to visiting Moscow but for me, Jeremy Bentham is a lot easier to get to. Unlike Lenin and Ramses II, Jeremy Bentham isn’t responsible for many deaths and whilst he may not quite be of the stature of John The Baptist, his forward thinking liberal philosophy definitely helped a lot of people

Recently I had 15 minutes to spare and thought I would go and visit Mr. Bentham who died in 1832 insisted that his body be preserved after his death as an ‘auto-icon’ so that he could be wheeled out at parties if his friends were missing him. He also wished to encourage others to donate their bodies to medical science, believing that individuals should make themselves as useful as possible, both in life and death.

Jeremy Bentham was also staunch atheist who described church teachings as ‘nonsense on stilts’ and so was opposed to a Christian burial. For more than 150 years, his body has been kept on public display in a glass case at University College London, however after a mummification mistake, his head was deemed too distasteful to show, and is now kept in safe where it is removed just once a year to check that skin and hair are not falling off though it is about to be once again put on public display where scientists at UCL will take samples of Bentham’s DNA to test theories that he may have had Asperger’s or autism, both of which have a strong genetic component. Subhadra Das, Curator of Collections at UCL Culture, said: “I think Bentham would certainly have approved of his head going on public display. It’s what he intended.

“It has also allowed scientists to test his DNA to see if he was autistic. We have been working with the Natural History Museum who have new techniques of studying ancient DNA.

“Studying ancient DNA is like looking at the shredded pages of a book, so much information is missing. And we have found that 99 per cent of the DNA taken has come from bacteria in his mouth. So it may be tricky to come to a firm conclusion.

“We want to explore what drove Bentham to donate his body, but also to address the challenges of putting this type of material on display”

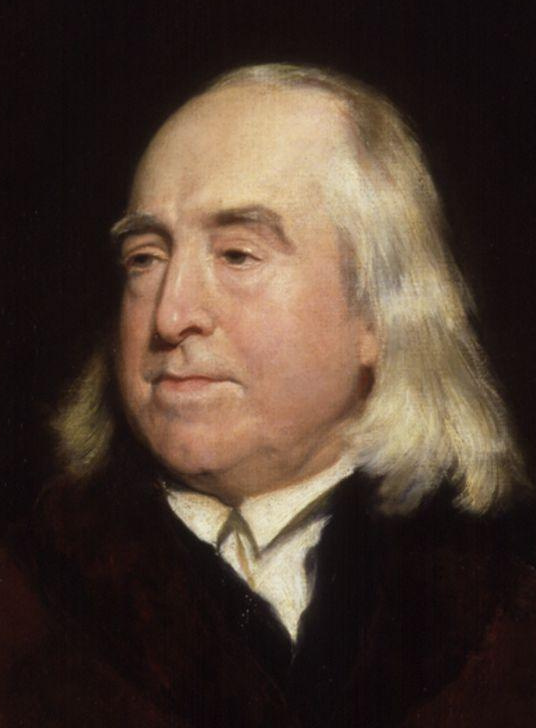

But what about Jeremy Bentham the man? Born in Spitalfields on 15th February 1748 he was a leading philosopher and social thinker of the 18th and early 19th century, establishing himself as a leading theorist in social and economic reform.

Bentham to a wealthy family that supported the Tory party. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father’s desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study Latin at the age of three. He had one surviving sibling, Samuel Bentham, with whom he was close.

He attended Westminster School and, in 1760, at age 12, was sent by his father to The Queen’s College, Oxford, where he completed his bachelor’s degree in 1763 and his master’s degree in 1766. He trained as a lawyer and, though he never practised, was called to the bar in 1769. He became deeply frustrated with the complexity of the English legal code, which he termed the “Demon of Chicane”.

When the American colonies published their Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the British government did not issue any official response but instead secretly commissioned London lawyer and pamphleteer John Lind to publish a rebuttal. His 130-page tract was distributed in the colonies and contained an essay titled “Short Review of the Declaration” written by Bentham, a friend of Lind, which attacked and mocked the Americans’ political philosophy.

He was pivotal in the establishment of Britain’s first police force, the Thames River Police in 1800 which was the precedent for Robert Peel’s reforms 30 years later. Amongst other things, he also developed plans for a more humane prison system which went on to influece later generations. He also argued for the rights of women, and for homosexuality to be legalised which puts him over 250 years in advance of much of the world.

For those who are interested on learning about Bentham’s ideas about crime and punishment then it can be found in his work ‘An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation’ which focuses on the principle of utility and how this view of morality ties into legislative practices. His principle of utility regards “good” as that which produces the greatest amount of pleasure and the minimum amount of pain and “evil” as that which produces the most pain without the pleasure. This concept of pleasure and pain is defined by Bentham as physical as well as spiritual. Bentham writes about this principle as it manifests itself within the legislation of a society. He lays down a set of criteria for measuring the extent of pain or pleasure that a certain decision will create.

The criteria are divided into the categories of intensity, duration, certainty, proximity, productiveness, purity, and extent. Using these measurements, he reviews the concept of punishment and when it should be used as far as whether a punishment will create more pleasure or more pain for a society. He calls for legislators to determine whether punishment creates an even more evil offence. Instead of suppressing the evil acts, Bentham argues that certain unnecessary laws and punishments could ultimately lead to new and more dangerous vices than those being punished to begin with, and calls upon legislators to measure the pleasures and pains associated with any legislation and to form laws in order to create the greatest good for the greatest number. He argues that the concept of the individual pursuing his or her own happiness cannot be necessarily declared “right”, because often these individual pursuits can lead to greater pain and less pleasure for a society as a whole. Therefore, the legislation of a society is vital to maintain the maximum pleasure and the minimum degree of pain for the greatest number of people.

However he was notably eccentric, reclusive and difficult to get hold of. He called his walking stick Dapple, his teapot Dickey, and kept an elderly cat named The Reverend Sir John Langbourne.

Bentham’s philosophy was baded around the principle that “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong”. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He advocated for individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and the decriminalising of homosexual acts. He called for the abolition of slavery, the death penalty, and physical punishment, including that of children. He has also become known in recent years as an early advocate of animal rights. Though strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law and natural rights both of which are considered “divine” or “God-given” in origin.

Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think …

These are just some of the incredible strands of belief that he developed and propogated and no doubt why he became a mentor to some of the biggest names in philopsophy including Robert Owen and John Stuart Mill. I remember spending some weeks in my first term at University becoming familiar with the writings of Bentham and John Stuart Mill as well as others from Aristotle, Jean Jacques Rousseau and Marx.

He became friends with leading figures in the French Revolution as well as figures in Independence movements in South and Central America.

In 1823, he co-founded the Westminster Review with James Mill as a journal for the “Philosophical Radicals” – a group of younger disciples through whom Bentham exerted considerable influence in British public life.[22] One was John Bowring, to whom Bentham became devoted, describing their relationship as “son and father”: he appointed Bowring political editor of the Westminster Review and eventually his literary executor. Another was Edwin Chadwick, who wrote on hygiene, sanitation and policing and was a major contributor to the Poor Law Amendment Act: Bentham employed Chadwick as a secretary and bequeathed him a large legacy.

For Bentham, transparency had moral value. For example, journalism puts power-holders under moral scrutiny. However, Bentham wanted such transparency to apply to everyone. This he describes by picturing the world as a gymnasium in which each “gesture, every turn of limb or feature, in those whose motions have a visible impact on the general happiness, will be noticed and marked down”. He considered both surveillance and transparency to be useful ways of generating understanding and improvements for people’s lives.

Economics

Bentham’s opinions about monetary economics were completely different from those of David Ricardo; however, they had some similarities to those of Henry Thornton. He focused on monetary expansion as a means of helping to create full employment. He was also aware of the relevance of forced saving, propensity to consume, the saving-investment relationship, and other matters that form the content of modern income and employment analysis. His monetary view was close to the fundamental concepts employed in his model of utilitarian decision making. His work is considered to be an early precursor of modern welfare economics.

Bentham stated that pleasures and pains can be ranked according to their value or “dimension” such as intensity, duration, certainty of a pleasure or a pain. He was concerned with maxima and minima of pleasures and pains; and they set a precedent for the future employment of the maximisation principle in the economics of the consumer, the firm and the search for an optimum in welfare economics.

Law reform

Bentham was the first person to aggressively advocate for the codification of all of the common law into a coherent set of statutes; he was actually the person who coined the verb “to codify” to refer to the process of drafting a legal code.[46] He lobbied hard for the formation of codification commissions in both England and the United States, and went so far as to write to President James Madison in 1811 to volunteer to write a complete legal code for the young country. After he learned more about American law and realized that most of it was state-based, he promptly wrote to the governors of every single state with the same offer.

During his lifetime, Bentham’s codification efforts were completely unsuccessful. Even today, they have been completely rejected by almost every common law jurisdiction, including England. However, his writings on the subject laid the foundation for the moderately successful codification work of David Dudley Field II in the United States a generation later.

Animal rights

Bentham is widely regarded as one of the earliest proponents of animal rights, and has even been hailed as “the first patron saint of animal rights”. He argued that the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, should be the benchmark, or what he called the “insuperable line”. If reason alone were the criterion by which we judge who ought to have rights, human infants and adults with certain forms of disability might fall short, too. In 1789, alluding to the limited degree of legal protection afforded to slaves in the French West Indies by the Code Noir, he wrote:

The day has been, I am sad to say in many places it is not yet past, in which the greater part of the species, under the denomination of slaves, have been treated by the law exactly upon the same footing, as, in England for example, the inferior races of animals are still. The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been witholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may one day come to be recognised that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?

Earlier in that paragraph, Bentham makes clear that he accepted that animals could be killed for food, or in defence of human life, provided that the animal was not made to suffer unnecessarily. Bentham did not object to medical experiments on animals, providing that the experiments had in mind a particular goal of benefit to humanity, and had a reasonable chance of achieving that goal. He wrote that otherwise he had a “decided and insuperable objection” to causing pain to animals, in part because of the harmful effects such practices might have on human beings. In a letter to the editor of the Morning Chronicle in March 1825, he wrote:

I never have seen, nor ever can see, any objection to the putting of dogs and other inferior animals to pain, in the way of medical experiment, when that experiment has a determinate object, beneficial to mankind, accompanied with a fair prospect of the accomplishment of it. But I have a decided and insuperable objection to the putting of them to pain without any such view. To my apprehension, every act by which, without prospect of preponderant good, pain is knowingly and willingly produced in any being whatsoever, is an act of cruelty; and, like other bad habits, the more the correspondent habit is indulged in, the stronger it grows, and the more frequently productive of its bad fruit. I am unable to comprehend how it should be, that to him to whom it is a matter of amusement to see a dog or a horse suffer, it should not be matter of like amusement to see a man suffer; seeing, as I do, how much more morality as well as intelligence, an adult quadruped of those and many other species has in him, than any biped has for some months after he has been brought into existence; nor does it appear to me how it should be, that a person to whom the production of pain, either in the one or in the other instance, is a source of amusement, would scruple to give himself that amusement when he could do so under an assurance of impunity.[50]

Gender and sexuality

Bentham said that it was the placing of women in a legally inferior position that made him choose, at the age of eleven, the career of a reformist. Bentham spoke for a complete equality between sexes.

The essay Offences Against One’s Self, argued for the liberalisation of laws prohibiting homosexual sex. The essay remained unpublished during his lifetime for fear of offending public morality. It was published for the first time in 1931.[54] Bentham does not believe homosexual acts to be unnatural, describing them merely as “irregularities of the venereal appetite”. The essay chastises the society of the time for making a disproportionate response to what Bentham appears to consider a largely private offence – public displays or forced acts being dealt with rightly by other laws. When the essay was published in the Journal of Homosexuality in 1978, the “Abstract” stated that Bentham’s essay was the “first known argument for homosexual law reform in England”.

Bentham is widely associated with the foundation in 1826 of London University (the institution that, in 1836, became University College London), though he was 78 years old when the University opened and played only an indirect role in its establishment. His direct involvement was limited to his buying a single £100 share in the new University, making him just one of over a thousand shareholders.

Bentham and his ideas can nonetheless be seen as having inspired several of the actual founders of the University. He strongly believed that education should be more widely available, particularly to those who were not wealthy or who did not belong to the established church; in Bentham’s time, membership of the Church of England and the capacity to bear considerable expenses were required of students entering the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. As the University of London was the first in England to admit all, regardless of race, creed or political belief, it was largely consistent with Bentham’s vision. There is some evidence that, from the sidelines, he played a “more than passive part” in the planning discussions for the new institution, although it is also apparent that “his interest was greater than his influence”.[60] He failed in his efforts to see his disciple John Bowring appointed professor of English or History, but he did oversee the appointment of another pupil, John Austin, as the first professor of Jurisprudence in 1829.

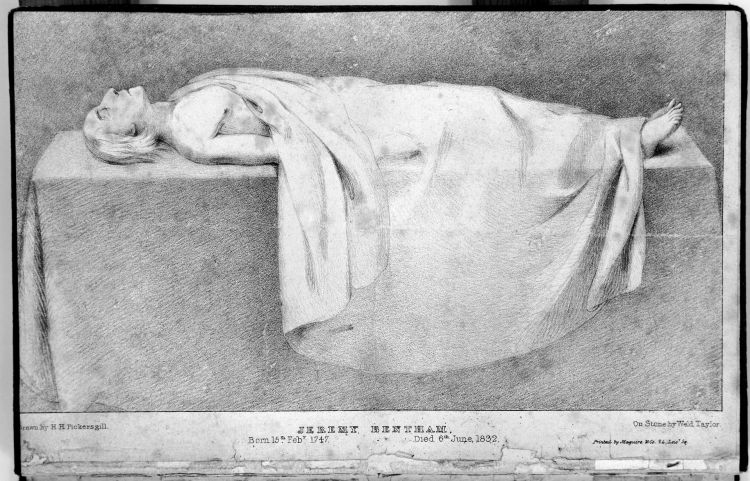

On his death in 1832, Bentham left instructions for his body to be first dissected, and then to be permanently preserved as an “auto-icon” (or self-image), which would be his memorial. This was done, and the auto-icon is now on public display at University College London (UCL). Because of his arguments in favour of the general availability of education, he has been described as the “spiritual founder” of UCL.

Bentham died on 6 June 1832 aged 84 at his residence in Queen Square Place in Westminster, London. He had continued to write up to a month before his death, and had made careful preparations for the dissection of his body after death and its preservation as an auto-icon.

On 8 June 1832, two days after his death, invitations were distributed to a select group of friends, and on the following day at 3 p.m., Southwood Smith delivered a lengthy oration over Bentham’s remains in the Webb Street School of Anatomy & Medicine in Southwark, London. The printed oration contains a frontispiece with an engraving of Bentham’s body partly covered by a sheet.

Bentham had intended the Auto-icon to incorporate his actual head, mummified to resemble its appearance in life. Southwood Smith’s experimental efforts at mummification, based on practices of the indigenous people of New Zealand and involving placing the head under an air pump over sulfuric acid and drawing off the fluids, although technically successful, left the head looking distastefully macabre, with dried and darkened skin stretched tautly over the skull. The auto-icon was therefore given a wax head, fitted with some of Bentham’s own hair. The real head was displayed in the same case as the auto-icon for many years, but became the target of repeated student pranks until it was locked away.

Amazing! I knew about him as the founder of utilitarianism and even the mummification of his head, but I have never read his views on animal rights or sexuality. Thank you for this fascinating post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, isn’t he the most amazingly forward thinking man ever? A man born in 1748 with views that are still more progressive than much of the world today. I must say, I didn’t remember his views on animal rights either. He must have been quite incredible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

far more revolutionary than most of the timid souls of today’s self policed social media generation!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That just made it to #1 on my list of “most interesting reads” for 2017!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank-you, that’s such an honour. He seems to be one of the most remarkable people in history. Even his 18th century views would still be too radical for many in the world today.

LikeLike