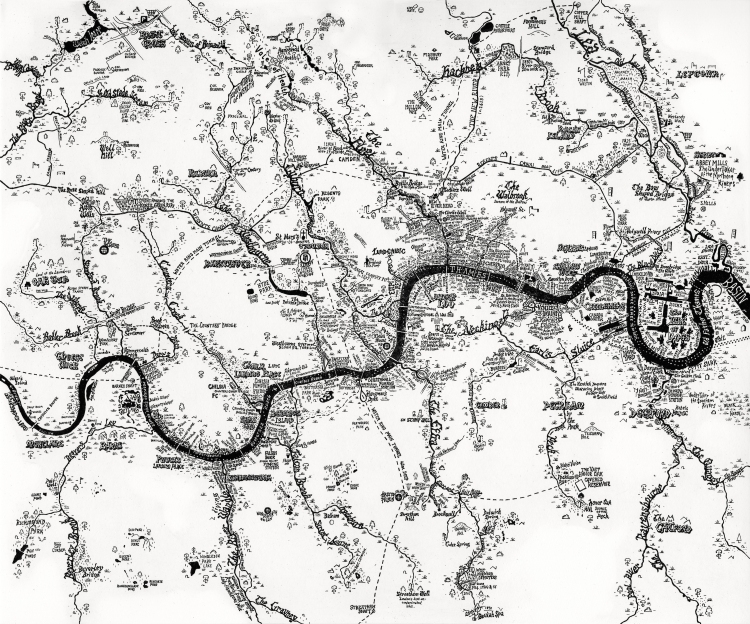

It’s easy to see London as one big mega city with just one river, what Londoners fondly call old Father Thames. When the tide of the river rises and falls it is almost as if you can see the city itself breathe. The Thames has always been the centre for life in the city even if these days it is more usually posing patiently for tourist drawings, etchings and photos. What is less known however is that London is full of other rivers. It makes sense doesn’t it? London is in a big natural bowl, hence the predilection for foggy winter days and hot and humid summers.

In fact there are at least 21 tributaries that flow into the Thames within the spread of Greater London itself, and that is just counting the main branches. Once tributaries, and tributaries of tributaries, are included the total becomes almost countless.

Many of these rivers flow quietly above ground, in plain sight but generally unnoticed beyond their neighbourhoods. Their enticing names echo London’s rural past – the Crane, the Darent, the Mutton Brook, the Pool River – or carry a whiff of the exotic – the Ching, the Moselle, the Quaggy, the Silk Stream. These rivers go about their business forgotten in the background and their banks so built up that they can be easily mistaken for canals or drains but many more inner London waterways have been deliberately hidden. London’s landscape was shaped by the hills and valleys these rivers created, but as the city grew they began to get in the way and were buried, bit by bit, under layers of streets and houses.

In the old days London needed all the rivers it could get. Rivers provided for almost everything for drinking water, for harbours and wharves, for mills, for tanneries, and for sluicing away the waste from both the people and the industries that they created. Long before the Victorians created the modern wonder that are the London sewers, the rivers were London acted as a natural sewage system.

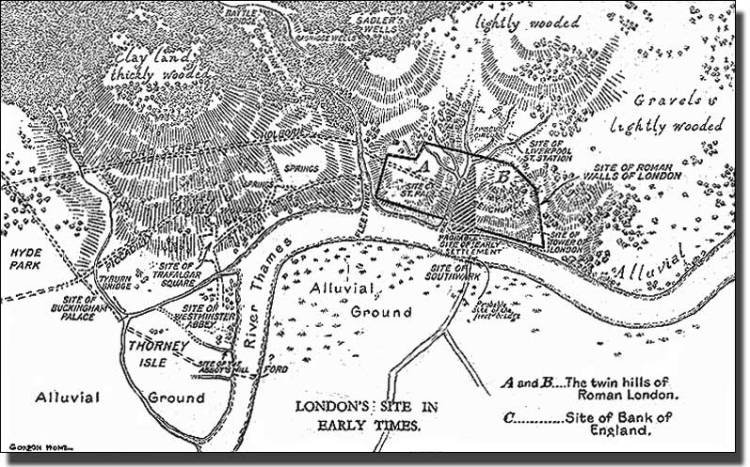

One of if not the first river to be buried over was the Walbrook. Not many people know of the Walbrook but it was the cornerstone on which London was founded. Whatever London was when the Romans arrive was centred around the junction of the Walbrook and the Thames. By the 1460’s though it was paved over and forgotten though archeologists working on the London Cross Rail project have found grisly evidence of some of the first inhabitants of London around Liverpool Street Station. The debris dug from the river – hoes and ploughshares, chisels and saws, scalpels and spatulas, the heads of forgotten gods and a collection of 48 human skulls tell the earliest London tales.

As London began to grow at the end of the 18th century, and then to mushroom beyond human comprehension during the 19th century, the rivers became a big problem. Floods, filth, stench and disease put off Georgian and Victorian house-buyers. In Mayfair, the Tyburn was tucked away under mews. In West Norwood, the Effra was buried deep under grids of new Victorian villas.

The Fleet was legendarily filthy but it was also hundreds of yards wide towards its discharge into the Thames and a major waterway. It was redesigned as a Venetian-style canal by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London but its refurbishment didn’t last too long before being overtaken by the then grim reality of urban life. Jonathan Swift, in 1710, wrote about the Fleet filled with:

“Sweepings from Butchers Stalls, Dung, Guts and Blood,

Drown’d Puppies, stinking Sprats, all drench’d in Mud,

Dead Cats and Turnip-Tops come tumbling down the Flood”

This awful environment led to many of the worst and poorest parts of London. Few wanted to live there but the prisoners of Newgate, Clerkenwell, Ludgate, Fleet & Bridewell prisons had little choice. So bad was the river that the locals took to digging wells for fresh water and many were proclaimed as having healing properties, though many now, like the rivers themselves can only be found in name only such as the famous Sadlers Wells theatre.

Everything from Welsh cheese to coals from Newcastle arrived at the Fleet wharves, and even the stones for Old St. Paul’s Cathedral were unloaded here. It is no surprise though that the lower Fleet was culverted in huge storm sewer tunnels where it has remained ever since. In effect the grand old River Fleet is one massive drain.

So many of the rivers may be hidden but they remain none the less, a hidden reminder of that London is a city that runs on many axis both on, above and below the ground. It is very hard to stop a river from flowing, so they have merely been diverted into the sewer system, often as part of Joseph Bazalgette’s monumental tunnelling programme during the 1860s and 1870s.

Even the hidden rivers can still be seen if you know where to look, flowing through culverts and under gratings. Sometimes they are hidden in plain sight. The Hampstead and Highgate Ponds are former reservoirs created by damming two streams that form the Fleet. Regent’s Park Lake was originally fed by the Tyburn, while the Serpentine was landscaped from the Westbourne in 1731 for the benefit of George II’s consort, Queen Caroline. Unfortunately the sewage problem eventually rendered both rivers unsuitable for ornamental ponds, and they were diverted away.

They also shaped London’s hills and valleys, a landscape layered over but still visible. Mysteriously steep roads, such as Pentonville Rise, make sense when seen as the sides of the Fleet Valley. The sharp dip as Piccadilly passes Green Park shows us where the Tyburn once crossed the road. The Oval cricket ground is oval because it was built into a bend in the Effra. Holborn Viaduct is a bridge with no river built on the site of an ancient Fleet crossing. From the viaduct the valley of the Fleet stretches away below, wide and deep, now occupied by Farringdon Street.

Names also contain clues obvious only in retrospect. Kilburn is named after the upper reaches of the Westbourne, also responsible for Bayswater, and once crossed by the Knight’s Bridge. Wandsworth has its very own river, the Wandle. Peckham Rye means “village by the River Peck”. Streets retain the river names: Effra Road and Westbourne Green, or just simply Neckinger and Walbrook.

Even Westminster Abbey itself once sat upon Thorney Island, now almost impossible to distinguish and unknown to but a handful, including the street planner who gave us Thorney Street. It was a low lying marshy island, perhaps suitably mystical being surrounded by rivers to build such a magnificent monument to God. Whilst all but the Thames has gone, the island would still flood more regularly if not for the Embankment.

Lost rivers really are everywhere, even in the places Londoners think they know intimately. The Tyburn runs directly beneath Buckingham Palace. The Walbrook is probably the most direct route into the Bank of England, running in a tunnel under its vaults. The Earl’s Sluice curves its way past Millwall football ground. The lost rivers link the familiar – the Royal Parks, Mayfair, the City, the South Bank – to places few visit – the back streets of Camberwell, Croydon, Earlsfield, Elephant and Castle, Gospel Oak, Kentish Town, Mitcham, Swiss Cottage, and West Norwood for example.

In a way London’s rivers are invisible threads which still bind London together even if we don’t know how or why. And if all of these lost rivers are simply to hard to find then I direct you to one of my favourite secret spots in London. Right in the middle of upmarket Sloane Square and it’s well-heeled tube station, there is a large green bridge or conduit that spans across the tracks and the platforms alike. Few believe me when I tell them it isn’t a passenger tunnel or full of cabling but is actually the River Westbourne, the same river that ran through Hyde Park and Hamsptead and which also lends its name to Kilburn. All in plain view of a generally very unknowing public.

More and more people are becoming aware of the hidden rivers of London and there is a government study going on to see about bringing some of them back to life above ground. It was understandable at the time that Georgians and Victorians would want to hide them away but now with technology and a sewer system, bringing these waterways back to life could enhance the landscape and quality of life immeasurably.

I hoped you liked this look at some of the secret and lost rivers of London. If you liked this post this you might be interested in the excellent London’s Lost Rivers book by Paul Talling.

That was an interesting article! I wish We had had more time to see more of London when we were there. I really liked it. We spent more time in the Cotswolds. I did get to go to Herrod’s…had a funny thing happen there…walked in and told my husband this is the store that Dodie Fayad’s father owns…I turned around and there he was walking towards me with his security guards…I said to my husband..”and there he is”! I had my arm stretched out pointing at him…he was about 5 feet from me and looking right at me….walked right past me and never blinked!! 😂 It was funny, because I said it real loud. We had another interesting thing happen in the Cotswolds….backed into a street light accidentally and had to pay $800 for it!😩 Guess it is good we didn’t stay there too long??!! Ha!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve met the Queen when I was 11 and seen William and Philip but not Diana or Dodie. I am meaning to write back properly to your other message 🙂 Wow you did well in the Cotswolds… street lights are quite hard to find there in places 🙂

LikeLike

Great story! If you guys ever have another frost fair I’m coming and I’m bringing the ginger!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Count me in too!

LikeLike

Great post

My favorite river is the Ravensbourne

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on sed30's Blog and commented:

Hard to believe given London modern day

LikeLiked by 1 person