So we now know all about the history of duels thanks to my post earlier this week but what if we want to duel ourselves?

There is always some idiot out there who flames you on Twitter, leaves a rude comment on our blogs or a frankly nonsensical review on Amazon about our books. Conventionally we are demanded to ignore them or commence hostilities in a pointless and insulting flame war over the internet.

I say our honour has been impuned and we demand satisfaction. Now, who is with me? I’m not altogether encouraging anyone to go out and duel as that would be (sadly?) highly illegal but suppose, just suppose that it is the only way then where do we start? Let’s journey back to the days where the answer to almost every insult, perceived and real, could be solved by way of a duel.

There is no reason too big or so petty that it is not worthy of a duel. On 23 March 1829, the Duke of Wellington and Earl of Winchelsea fought a duel at Battersea Fields in South London simply because the Earl had reproached the Iron Duke for not being tough enough on Catholics.

The first thing to do is of course to

1: Choose your rules

It is 1820. You are a handsome young Northumbrian travelling through London named Robert Broadale and you want to duel somebody. But how?

The Wild West may indeed all ready by wild but a quick-draw shoot-out at High Noon is completely out of the question for a gentleman. How about the French Code? With 85 rules, it would be hard to find a more gentlemanly code to duel by, but it is hard to concentrate enough to remember everything when all you know is that you want to give that cheeky rapscallion James Pinkerton his comeuppance.

Thankfully there is no need to worry now that we can go by the Luckily, the streamlined Irish Code Duello (1777) It only has 25 rules, plus a couple of footnotes about knee-bending. Huzzah! But one of those rules is that your opponent, the challenged party, gets to choose the weapons. Damn it!

What happens if that oik Pinkerton might pick swords. You hate swords. You bunked off fencing lessons at Eton to smoke and play cards. Luckily, rule XVI says you can avoid a swordfight by swearing on your honour that you are no swordsman. Pistols it is! Huzzah!

2: Choose your provocation

James Pinkerton is a monstrous cad, and you want him dead. But you can’t duel someone just because you don’t like them. One duels to defend one’s honour – or the honour of a woman in one’s care – and to demand satisfaction after a slight, insult or violent blow.

The type of offence decides the type of duel. For example, if your foe called you a liar, he is allowed the chance to call the whole thing off with an outright apology after the second exchange of bullets, or to offer an explanation after round three (if you’re both still alive by then). If he punched you, no verbal apology can suffice, but he can offer you a stick to beat him with in lieu of a duel (rule V).

It seems half the rules in the Code Duello are there to make you change your mind. Do they want us to have a duel or not? Rule XXI (“Seconds are bound to attempt a reconciliation”) means your chum Aubrey has a duty to talk you out of it. But it’s no use: you want Pinkerton’s blood.

One night the rapscallion gives you a shove while you are drunk at a party. You can’t really tell what’s going on (as you’re also off your face on laughing-gas), but that probably constitutes a violent blow and is justification enough.

Slurring slightly, you challenge him to a duel. It’s against rule XV (“challenges are never to be delivered at night”), but that scoundrel had insulted your wife, or at least you think he did! Sometimes, rules are there to be broken.

3: Choose your meeting-place

Technically, the challenged party gets to choose. But it needs to be somewhere secluded. You don’t want any undue attention. Duelling is illegal. It’s basically just murder with waistcoats. Admittedly, it was once an acceptable alternative to a court case (a hangover from the medieval idea of trial by combat), but Queen Elizabeth outlawed all that in 1571.

In these more enlightened times, even the Americans are starting to quibble about it. There was a real palaver a few years ago when their vice-president Aaron Burr shot and killed a politician called Alexander Hamilton. Two centuries from now, that duel will inspire a popular hip-hop musical, but hip-hop hasn’t been invented yet so there is no need to let that deter you.

It’s a good idea to have your duel on a no-man’s-land between two parishes; the local law enforcement will all assume it’s somebody else’s problem.

You meet Pinkerton on a misty, swampy island, covered in dense woodland with just one small glade that happens to have an old gypsy woman living on it. Perfect. Honour will be satisfied, Huzzah!

4: Make sure everyone turns up

You’re here and Pinkerton is here. But that’s not enough people. You both need a ‘second’ (essentially a back-up duellist). And you should really have a separate adjudicator who can give the signal to begin – a dropped handkerchief is customary.

You will also need a doctor, paid in advance, who will probably turn his back during the duel so he can deny knowing exactly what happened, in case he ever needs to testify about it (Burr’s physician David Hosack did this during his duel with Hamilton). Don’t worry, you should be able to get your money back if you come through this uninjured and if you’re dead then there are bigger things to worry about.

All present and correct? Good.

5: The duel begins – don’t panic!

Cheer up. Guns are still a bit rubbish really, people are generally merciful, and only a small number of duels end in death. Remember rule XXII: “Any wound sufficient to agitate the nerves, and necessarily make the hand shake, must end the business for that day.” Besides, it’s not uncommon for gentlemen to deliberately waste their first shot.

Unfortunately, you’re fighting by the Irish Code Duello, which explicitly forbids ‘deloping’, or shooting elsewhere (the sky, the ground, etc.) out of pity for your opponent.

You have agreed to shoot “at pleasure”, which means you don’t need to fire as soon as the handkerchief falls. A thought strikes you: if you shoot first and miss, Pinkerton cannot simply shoot at a passing pigeon. According to the Irish rules – and you’re beginning to wish you’d learnt the French version – he must aim for a living human being. He will have all the time he needs to line up a fatal shot.

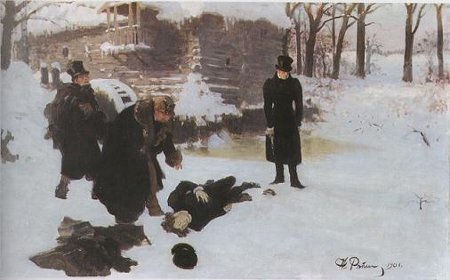

You glance at the handkerchief. It fall… good luck!

But why was duelling such an integral part of society? In our modern age, solving a problem by asking a chap to step outside is generally considered an immature, low-class thing to do.

The following text is taken from a 2010 edition of The Art Of Manliness

But for many centuries, challenging another man to a duel was not only considered a pinnacle of honour, but was a practice reserved for the upper-classes, those deemed by society to be true gentlemen.

“A man may shoot the man who invades his character, as he may shoot him who attempts to break into his house.” -Samuel Johnson

While dueling may seem barbaric to modern men, it was a ritual that made sense in a society in which the preservation of male honor was absolutely paramount. A man’s honor was the most central aspect of his identity, and thus its reputation had to be kept untarnished by any means necessary. Duels, which were sometimes attended by hundreds of people, were a way for men to publicly prove their courage and manliness. In such a society, the courts could offer a gentleman no real justice; the matter had to be resolved with the shedding of blood.

How did this violent way to prove one’s manhood evolve? Let’s take a look at the history of the affair of honor and the code duello which governed it.

Origins in Single Combat

In the ancient tradition of single combat, each side would send out their “champion” as the representative of their respective armies, and the two men would fight to the death. This contest would sometimes settle the matter, or would serve only as a prelude to the ensuing battle, a sign to which side the gods favored. Prominent single combat battles have made their way into the records of history and legend, such as the battle between David and Goliath in the Valley of Elah and Achilles’ clashes with both Ajax and Hector in Homer’s Iliad. As warfare evolved, single combat became increasingly less prevalent, but the ethos of the contest would lend inspiration to the gentlemen’s duel.

Dueling in Europe

“A coward, a man incapable either of defending or of revenging himself, wants one of the most essential parts of the character of a man.” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

Dueling began in ancient Europe as “trial by combat,” a form of “justice” in which two disputants battled it out; whoever lost was assumed to be the guilty party. In the Middle Ages, these contests left the judicial sphere and became spectator sports with chivalrous knights squaring off in tournaments for bragging rights and honor.

But dueling really became mainstream when two monarchs got into the act. When the treaty between France and Spain broke down in 1526, Frances I challenged Charles V to a duel. After a lot of back and forth arguing about the arrangements of the duel, their determination to go toe to toe dissipated. But the kings did succeed in making dueling all the rage across Europe. It was especially popular in France; 10,000 Frenchmen are thought to have died during a ten year period under Henry IV. The king issued an edict against the practice, and asked the nobles to submit their grievances to a tribunal of honor for redress instead. But dueling still continued, with 4,000 nobles losing their lives to the practice during the reign of Louis XIV.

Dueling in America

“Certainly dueling is bad, and has been put down, but not quite so bad as its substitute — revolvers, bowie knives, blackguarding, and street assassinations under the pretext of self-defense.” -Colonel Benton

Dueling came to American shores right along with her first settlers. The first American duel took place in 1621 at Plymouth Rock.

Dueling enjoyed far more importance and prevalence in the South than the North. Antebellum society placed the highest premium on class and honor, and the duel was a way for gentlemen to prove both.

The majority of Southern duels were fought by lawyers and politicians. The law profession was (as it is now) completely saturated, and the competition for positions and cases was acute. In this dog-eat-dog society, jostling for position and maintaining an honorable reputation meant everything. Every perceived slight or insult had to be answered swiftly and strongly to save face and one’s position on the ladder to respect and success.

And while we tend to paint modern politics as uncivil and romanticize the past, politicians of the day slung bullets in addition to mud. Legislators, judges, and governors settled their differences with the duel, and candidates for office debated their issues on the “field of honor.” Political showmanship of the day involved timing a duel for right before an election and splashing the results in the papers.

Dueling and Violence

“The views of the Earl are those of a Christian, but unless some mode is adopted to frown down by society the slanderer, who is worse than a murderer, all attempts to put down dueling will be in vain.” -Andrew Jackson

Despite putting on a courageous front, no gentleman relished having to fight a duel and risk both killing and being killed (well, perhaps with the exception of Andrew “I fought at least 14 duels” Jackson). Thus duels were often not intended to be fights to the death, but to first blood. A duel fought with swords might end after one man simply scratched the arm of the other. In pistol duels, it was often the case that a single volley was fired, and assuming both men had survived unscathed, satisfaction was deemed to be achieved through their mutual willingness to risk death. Men sometimes aimed for their opponent’s leg or even deliberately missed, desiring only to satisfy the demands of honor. Only about 20% of duels ended in a fatality.

Duels founded on greater insults to a man’s honor, however, were often designated to go well beyond first blood. Some were carried out under the understanding that satisfaction was not gained until one man was incapacitated, while the gravest insults required a mortal blow.

To us, duels seem like a pointlessly barbaric way to settle disputes; going into a duel the odds were nearly 100% that one man or both would be wounded or killed. And, adding insult to injury, it could very well be the innocent party who was slain.

Even at the time, there were many critics that argued that dueling was unnecessarily violent and contrary to morality, religion, common sense, and indeed, antithetical to the very concept of honor itself. But there were also those who argued that dueling actually prevented violence.

The idea was that single combat warriors averted endless bloody feuds between groups and families ala the Hatfields and McCoys. The duels nipped these potential feuds in the bud as insults were given immediate redress, with satisfaction given to both parties.

The practice was also thought to increase civility throughout society. To avoid being challenged to the duel, gentlemen were careful not to insult or slight others. The courtly, formal manners this time period is famous for-the stately dress, the bowing, toasting, and flowery language-were designed to convey honorable intentions and avoid giving offense. Jealousies and resentments had to be repressed and covered with politeness.

In the 1836 manual, The Art of Duelling, the author summarizes the pro-dueling perspective of the time with comments that seem remarkable to the modern ear:

“The practice is severely censured by all religious and thinking people; yet it has very justly been remarked, that ‘the great gentleness and complacency of modern manners, and those respectful attentions of one man to another, that at present render the social discourses of life far more agreeable and decent, than among the most civilized nations of antiquity; must be ascribed, in some degree to this absurd custom.’ It is certainly both awful and distressing to see a young person cut off suddenly in a duel, particularly if he be the father of a family; but the loss of a few lives is a mere trifle, when compared with the benefits resulting to Society at large.

I should consider it very unwise in the members of government, to adopt any measures that would enforce the prohibition of duelling…the man who falls in a duel, and the individual who is killed by the overturn of a stage-coach, are both unfortunate victims to a practice from which we derive great advantage. It would be absurd to prohibit stage-travelling-because, occasionally, a few lives are lost by an overturn.”

Dueling Necessities

The components of the gentleman’s duel were often quite varied. The challenged party was usually given the choice of weapons, and the possibilities were endless. Duels have been fought with everything from sabers to billiard balls. A duel was once even fought over the skies of Paris, with the participants utilizing blunderbusses in an attempt to rupture each other’s hot air balloons. One succeeded, sending the opposing man and his comrade plummeting to their death, while the winner floated triumphantly away.

Swords were the weapon of choice until the 18th century, when the transition to pistols made dueling more democratic (fencing took skill-a man might challenge another to a duel, spend a year learning swordsmanship, and then return to fight the duel. But nearly anyone could pull a trigger). As the practice of using guns grew in prominence, arms makers began to create sets of pistols specifically built for dueling. The idea behind this practice was simple. If two men were going to engage in a duel, their “equipment” needed to be as similar as possible so as not to give one man an unfair advantage over the other. Thus, by the latter 18th century, sets of dueling pistols were being produced by fine arms makers throughout Europe. Dueling pistols were often smooth bored pistols, and usually fired quite large rounds. Calibers of .45, .50, or even .65 (caliber = inches of diameter) were in common usage. The pistols were made to exact specifications and were tested to ensure that they were as equal in performance and appearance as possible. A man’s dueling pistols were a prized possession, an heirloom passed down from father to son.

Code Duello: The Dueling Code

“A duel was indeed considered a necessary part of a young man’s education…When men had a glowing ambition to excel in all manner of feats and exercises they naturally conceived that manslaughter, in an honest way (that is, not knowing which would be slaughtered), was the most chivalrous and gentlemanly of all their accomplishments. No young fellow could finish his education till he had exchanged shots with some of his acquaintances. The first two qualifications always asked as to a young man’s respectability and qualifications, particularly when he proposed for a lady wife, were ‘What family is he of? And ‘Did he ever blaze?” -19th century Irish duelist

Dueling code evolved over the centuries as weapons and notions of honor changed. Proper dueling protocol in the 17th and 18th centuries was recorded in such works as The Dueling Handbook by Joseph Hamilton and The Code of Honor by John Lyde Wilson. While the dueling code varied by time period and country, many aspects of the code were similar.

Despite our romanticized notion of duels as being fought only over the most grievous of disputes, duels could often arise from matters most trivial-telling another man he smelled like a goat or spilling ink on a chap’s new vest. But they were not spontaneous affairs in which an insult was given and the parties marched immediately outside to do battle (in fact, striking another gentleman made you a social pariah). A duel had to be conducted calmly and coolly to be dignified, and the preliminaries could take weeks or months; a letter requesting an apology would be sent, more letters would be exchanged, and if peaceful resolution could not be reached, plans for the duel would commence.

The first rule of dueling was that a challenge to duel between two gentleman could not generally be refused without the loss of face and honor. If a gentleman invited a man to duel and he refused, he might place a notice in the paper denouncing the man as a poltroon for refusing to give satisfaction in the dispute.

But one could honorably refuse a duel if challenged by a man he did not consider a true gentleman. This rejection was the ultimate insult to the challenger.

The most common characteristic of a duel between gentlemen was the presence of a “second” for both parties. The seconds were gentlemen chosen by the principal participants whose job it was to ensure that the duel was carried out under honorable conditions, on a proper field of honor and with equally deadly weapons. More importantly, it was the seconds (usually good friends of the participating parties) who sought a peaceful resolution to the matter at hand in hopes of preventing bloodshed.

Once the challenge to duel was given, several issues had to be settled before the matter could be resolved. The challenger would first allow his foe the choice of weapons and conditions of the combat, and a time would be set for the event. Seconds were responsible for locating a proper dueling ground, usually a remote area away from witnesses and law enforcement, since dueling remained technically illegal in most states, though rarely prosecuted. Duels were sometimes even fought on sandbars in rivers where the legal jurisdiction of the time was hazy at best.

Honor was not only given for showing up for the duel-proper coolness and courage under fire was also required to uphold one’s reputation. A gentleman was not to show his fear. If he stepped off the mark, his opponent’s second had the right to shoot him on the spot.

The End of the Dueling Age

Many modern men mistakenly believe that dueling was a rare occurrence in history; a last resort only appealed to in the case of serious matters or by two overly hot-headed men. In fact, from America to Italy, tens of thousands of duels took place and the practice was quite common among the upper classes.

But dueling’s popularity eventually waned at the end of the 19th century, lingering longer in Europe than America. Stricter anti-dueling laws were passed, and sometimes even enforced.

The bloodshed of the Civil War on this continent, and the Great War on the other, also dampened enthusiasm for the duel. Despite our modern romanticism for dueling, it was a practice that hewed down young men in the prime of their life. Having lost millions of their promising youth in battle, felling those who remained became distasteful.

Additionally, Southern society was vastly transformed in the aftermath of the Civil War. The aristocracy was shattered; busy with Reconstruction and rebuilding, there was less time and inclination to duel. A man’s prestige and position in society became less about his family, reputation, and most of all, honor, than it did about cash. Disputes were taken not to the field of honor but to the courts, with vindication given by “pale dry money instead of wet red blood.”

Duels of the seventeenth and eighteenth century were conducted primarily with swords, although by the late eighteenth century they were fought with pistols. Fortunately, pistol dueling fell out of fashion by the mid-nineteenth century. However, prior to its demise a “Royal Code of Honor” existed and was adhered to by dueling Principals and Seconds. The code stated, “No duel can be considered justifiable, which can be declined with honor, therefore, an appeal to arms should always be the last resource.”

This meant that great lengths were taken to avoid duels. For instance, if a gentleman experienced violence or abusive treatment, he was to seek redress for the abuse or assault through the Courts of Law. Or if a the challenged party refused to provide satisfaction, then a notification in a public journal was to be considered more “creditable” than personal violence. Additionally, every apology proposed was to be dignified and every attempt made to avoid further or unnecessary degradation of an adversary was to occur.

Even when a pistol duel was undertaken, it was expected that after each discharge of the pistols there would be attempts to resolve the issue. However, when a duel did occur, duelers were expected to behavior appropriately. The were to use the utmost delicacy and politeness at every stage because as one author noted, “the first essential of a duel is a perfect correctness of behaviour.” Rules for pistol dueling were so important, the Royal Code of Honor noted that “should any individual attempt to deviate from [the] rules … his adversary will be justified in refusing to recognize him as a gentleman.”

Etiquette and rules for dueling included the following:

- No duels were to be fought on Sunday, on a day of a Festival, or near a place of public worship.

- A gentleman, who valued his own reputation, would not fight a duel with, nor act as a Second to, a person who aggravated and increased discord or violence by striking someone with his fist, a stick, or a glove or called the person a liar, coward, or any other irritating name.

- The Second was to be “a ‘man who [was] not passion’s slave,’” and no gentleman was to accept the position of a Second, “without first receiving from his friend, a written statement of the case upon his honor.”

- When “bosom friends, fathers of large, or unprovided families, or very inexperienced youths … [were] to fight, the Seconds [were to] … be doubly justified in their solicitude for reconciliation.”

- A Principal was not to “wear light coloured clothing, ruffles, military decorations, or any other … attractive object, upon which the eye of his antagonist [could] … rest,” as it could affect the outcome of the duel.

- The time and place were to be as convenient as possible to surgical assistance and to the combatants. The Royal Code of Honor noted that “special precaution should invariable be used, to prevent … carrying wounded gentlemen over walls, ditches, gates, stiles, or hedges; or too great a distance to a dwelling.”

- The parties were to salute each other upon meeting “offering this evidence of civilization.”

- As there were always unexpected advantages — the terrain or light — advantages were to be “decided by the toss of three, five, or seven coins … carefully shaken in a hat,” and the challenged party was entitled to the first toss, the challenger to the second, and so on until the advantages were decided.

- No gentleman was allowed to wear spectacles unless they used them on public streets.

- There was to be at least 10 yards distance between the combatants.

- The Seconds were to present pistols to Principals and the pistols were not to be cocked before delivery.

- The combatants were to present and fire together without resting on their aim at the agreed upon signal.

- After each discharge the Seconds were to “mutually and zealously attempt a reconciliation.”

- Each combatant would fire one shot and if neither was hit but the challenger satisfied, the duel was declared over. However, if the challenger was unsatisfied, the duel continued. But no more than three exchanges of fire were allowed, as to exchange more shots was considered barbaric.

- The offended party determined what conclusion was acceptable and there were three possible outcomes: 1) first blood (the duel ended when one combatant was wounded); 2) the duel continued until one combatant was physically unable to proceed; or 3) death, a combatant was fatally wounded.

- Neither the Principal nor the Second were to abandon an injured gentlemen “without … securing for him a proper conveyance from the field.”

- After the duel was over, the Seconds were to remind friends and relatives of the combatants, that the slightest indiscretion could renew the breach and Principals were also to abstain from conversation upon the subject so as not to reopen closed wounds.

Would trolling someone and counter trolling be considered duelling?

While folks may not resort to physical violence, might we not duel or spar trough words you think?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think so and probably like how society generally was against duelling and looked down on them, we often feel similarly to twitter trolls.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed!

LikeLike

Excellent. Just curious, how do you find your subject matter?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is an interesting question. I never imagined that after 530+ posts, this blog would still be going strong. For the first year or two I would have a backlog of topics to write on. These days if I am lucky then I know what I will write for the coming week whilst at other times, it is almost a last minute decision. So really it is whatever comes to mind. Occasionally when I am out and about or reading and I come across something interesting then I put a reminder on my list as a backup for those times when I have no inspiration. I hope the quality is keeping as high as ever!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly is! Always interesting. 🙂

LikeLike

Very good post, but you left one thing out… did I hit that cad Pinkerton? Or did he kill me?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad that you enjoyed it. You’ll be glad to know that cad Pinkerton fired first but barely missed, ripping a hole through your dandy white shirt sleeve. You finished him off good a proper and what’s more won the heart of young Lady Mablethorpe who is the brother of your second. As things stand you’re set to marry into the family and strike it rich as she is the heiress to an international shipping company. Well done you, do remember me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m happy everything is working out so well, but that cad Pinkerton ruined my best white shirt!

LikeLiked by 1 person