It’s hard to imagine a when men would fight for honour almost at the drop of a hat or indeed a white handkerchief but there was a time when this was de rigueuer. There used to be thousands of duels and this penchant for legalised violence would be what descended into the infamous cowboy shoot-outs of the American Wild West and those awkward moments in British pubs when you might be asked to pop outside.

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two individuals with matched weapons in accordance with agreed-upon rules.

Duels in this form were chiefly practiced in early modern Europe with precedents in the medieval code of chivalry, and continued into the modern period (19th to early 20th centuries) especially among military officers.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly fought with swords (the rapier, and later the smallsword). But beginning in the late 18th century in England, duels were more commonly fought using pistols. Fencing and pistol duels continued to co-exist throughout the 19th century.

The duel was based on a code of honour. Duels were fought not so much to kill the opponent as to gain “satisfaction”, that is, to restore one’s honour by demonstrating a willingness to risk one’s life for it, and as such the tradition of dueling was originally reserved for the male members of nobility; however, in the modern era it extended to those of the upper classes generally. On rare occasions, duels with pistols or swords were fought between women; these were sometimes known as petticoat duels.

Legislation against dueling goes back to the medieval period. The Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) outlawed duels. From the early 17th century, duels became illegal in the countries where they were practiced. However, there was usually a delay of centuries between the duel becoming illegal and it actually ceasing to be a common occurrence.

Dueling largely fell out of favor in England by the mid-19th century and in Continental Europe by the turn of the 20th century. Dueling declined in the Eastern United States in the 19th century and by the time the American Civil War broke out, dueling had begun to decline, even in the southern states. Public opinion, not legislation, caused the change.

It was all so much different in the centuries that followed early medieval English Knights and their codes of honour that became chivalry and what we would more broadly label good manners and gentlemanly behaviour. During the early Renaissance, dueling established the status of a respectable gentleman, and was an accepted manner to resolve disputes.

The duel arrived in the British Isles at the end of the sixteenth century with the influx of Italian honour and courtesy literature – most notably Baldassare Castiglione’s Libro del Cortegiano (Book of the Courtier), published in 1528, and Girolamo Muzio’s Il Duello, published in 1550. These stressed the need to protect one’s reputation and social mask and prescribed the circumstances under which an insulted party should issue a challenge. The word duel was introduced in the 1590s, modelled after Medieval Latin duellum (an archaic Latin form of bellum “war”, but associated by popular etymology with duo “two”, hence “one-on-one combat”).

Soon domestic literature was being produced such as Simon Robson’s The Courte of Ciuill Courtesie, published in 1577. Dueling was further propagated by the arrival of Italian fencing masters such as Rocco Bonetti and Vincento Saviolo. By the reign of James I dueling was well entrenched within a militarised peerage – one of the most important duels being that between Edward Bruce, 2nd Lord Kinloss and Edward Sackville (later the 4th Earl of Dorset) in 1613, during which Bruce was killed.

James I encouraged Francis Bacon as Solicitor-General to prosecute would-be duellists in the Court of Star Chamber, leading to about two hundred prosecutions between 1603 and 1625. He also issued an edict against dueling in 1614 and is believed to have supported production of an anti-dueling tract by the Earl of Northampton. Dueling however, continued to spread out from the court, notably into the army.

In the mid-seventeenth century, duelling was less popular for a while as it impeded by the activities of the Parliamentarians whose Articles of War specified the death penalty for would-be duellists. Nevertheless, dueling survived and increased markedly with the Restoration. Among the difficulties of anti-dueling campaigners was that although monarchs uniformly proclaimed their general hostility to dueling, they were nevertheless very reluctant to see their own favourites punished. In 1712 both the Duke of Hamilton and Charles 4th Baron Mohun were killed in a duel induced by political rivalry and squabbles over an inheritance.

By the 1780s, the values of the duel had spread into the broader and emerging society of gentlemen. Research shows that much the largest group of later duellists were military officers, followed by the young sons of the metropolitan elite (see Banks, A Polite Exchange of Bullets). Dueling was also popular for a time among doctors and, in particular, in the legal professions. Quantifying the number of duels in Britain is difficult, but there are about 1,000 attested between 1785 and 1845 with fatality rates running at at least 15% and probably somewhat higher.

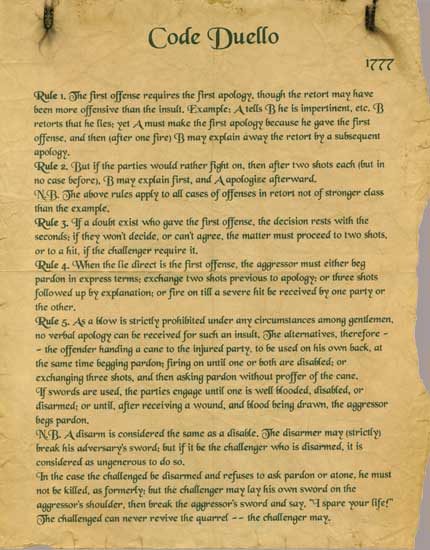

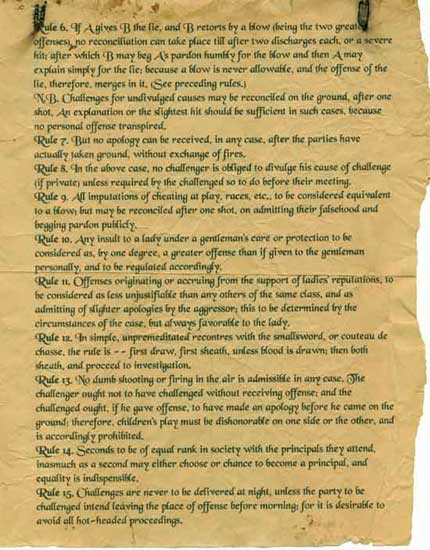

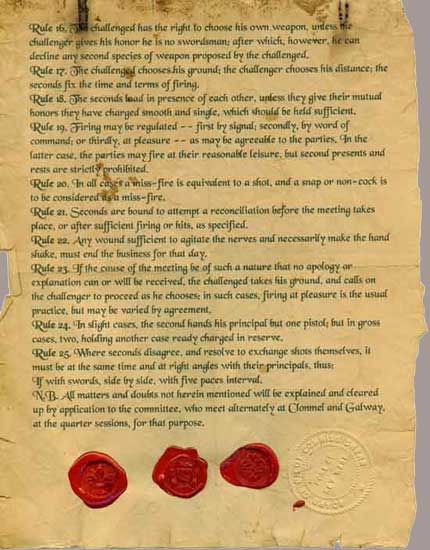

In 1777, at the Summer assizes in the town of Clonmel, County Tipperary, a code of practice was drawn up for the regulation of duels that would soon be adopted throughout the British Isles and much of the USA.

Rule 1.—The first offence requires the apology, although the retort may have been more offensive than the insult.

—Example: A. tells B. he is impertinent, &C.; B. retorts, that he lies; yet A. must make the first apology, because he gave the first offence, and then, (after one fire,) B. may explain away the retort by subsequent apology .

Dueling remained highly popular in European society, despite various attempts at banning the practice.

According to Ariel Roth, during the reign of Henry IV, over 4,000 French aristocrats were killed in duels “in an eighteen-year period” while a twenty-year period of Louis XIII’s reign saw some eight thousand pardons for “murders associated with duels”. Roth also notes that thousands of men in the Southern United States “died protecting what they believed to be their honor.”

The first published code duello, or “code of dueling”, appeared in Renaissance Italy. The first formalised national code was France’s, during the Renaissance. In 1777, a code of practice was drawn up for the regulation of duels, at the Summer assizes in the town of Clonmel, County Tipperary, Ireland. A copy of the code, known as ‘The twenty-six commandments’, was to be kept in a gentleman’s pistol case for reference should a dispute arise regarding procedure. During the Early Modern period, there were also various attempts by secular legislators to curb the practice. Queen Elizabeth I in England officially condemned and outlawed dueling in 1571, shortly after the practice had been introduced to our country.

However, the tradition had become deeply rooted in European culture as a prerogative of the aristocracy, and these attempts largely failed. For example, King Louis XIII of France outlawed dueling in 1626, a law which remained in force for ever afterwards, and his successor Louis XIV intensified efforts to wipe out the duel. Despite these efforts, dueling continued unabated, and it is estimated that between 1685 and 1716, French officers fought 10,000 duels, leading to over 400 deaths.By the late 18th century, Enlightenment era values began to influence society with new self-conscious ideas about politeness, civil behaviour and new attitudes towards violence. The cultivated art of politeness demanded that there should be no outward displays of anger or violence, and the concept of honour became more personalized.

By the late 18th century, Enlightenment era values began to influence society with new self-conscious ideas about politeness, civil behaviour and new attitudes towards violence. The cultivated art of politeness demanded that there should be no outward displays of anger or violence, and the concept of honour became more personalized.

By the 1770s the practice of dueling was increasingly coming under attack from many sections of enlightened society, as a violent relic of Europe’s medieval past unsuited for modern life. As England began to industrialise and benefit from urban planning and more effective police forces, the culture of street violence in general began to slowly wane. The growing middle class maintained their reputation with recourse to either bringing charges of libel, or to the fast-growing print media of the early nineteenth century, where they could defend their honour and resolve conflicts through correspondence in newspapers.

Influential new intellectual trends at the turn of the nineteenth century bolstered the anti-dueling campaign; the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham stressed that praiseworthy actions were exclusively restricted to those that maximize human welfare and happiness, and the Evangelical notion of the “Christian conscience” began to actively promote social activism. Individuals in the Clapham Sect and similar societies, who had successfully campaigned for the abolition of slavery, condemned dueling as ungodly violence and as an egocentric culture of honour.

Dueling became popular in the United States – the former United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton was killed in a duel against the sitting Vice President Aaron Burr in 1804. Between 1798 and the Civil War, the US Navy lost two-thirds as many officers to dueling as it did in combat at sea, including naval hero Stephen Decatur. Many of those killed or wounded were midshipmen or junior officers. Despite prominent deaths, dueling persisted because of contemporary ideals of chivalry, particularly in the South, and because of the threat of ridicule if a challenge was rejected.

By about 1770, the duel underwent a number of important changes in England. Firstly, unlike their counterparts in many continental nations, English duelists enthusiastically adopted the pistol, and sword duels dwindled. Special sets of dueling pistols were crafted for the wealthiest of noblemen for this purpose. Also, the office of ‘second’ developed into ‘seconds’ or ‘friends’ being chosen by the aggrieved parties to conduct their honour dispute. These friends would attempt to resolve a dispute upon terms acceptable to both parties and, should this fail, they would arrange and oversee the mechanics of the encounter.

In the United Kingdom, to kill in the course of a duel was formally judged as murder, but generally the courts were very lax in applying the law, as they were sympathetic to the culture of honour. This attitude lingered on – Queen Victoria even expressed a hope that Lord Cardigan, prosecuted for wounding another in a duel, “would get off easily”. The Anglican Church was generally hostile to dueling, but non-conformist sects in particular began to actively campaign against it.

By 1840, dueling had declined dramatically; when the 7th Earl of Cardigan was acquitted on a legal technicality for homicide in connection with a duel with one of his former officers, outrage was expressed in the media, with The Times alleging that there was deliberate, high level complicity to leave the loop-hole in the prosecution case and reporting the view that “in England there is one law for the rich and another for the poor” and The Examiner describing the verdict as “a defeat of justice”.The last fatal duel between Englishmen in England occurred in 1845, when James Alexander Seton had an altercation with Henry Hawkey over the affections of his wife, leading to a duel at Southsea. However, the last fatal duel to occur in England was between two French political refugees, Frederic Cournet and Emmanuel Barthélemy near Englefield Green in 1852; the former was killed. In both cases, the winners of the duels, Hawkey and Barthélemy, were tried for murder. But Hawkey was acquitted and Barthélemy was convicted only of manslaughter; he served seven months in prison. However, in 1855, Barthélemy was hanged after shooting and killing his employer and another man

The last fatal duel between Englishmen in England occurred in 1845, when James Alexander Seton had an altercation with Henry Hawkey over the affections of his wife, leading to a duel at Southsea. However, the last fatal duel to occur in England was between two French political refugees, Frederic Cournet and Emmanuel Barthélemy near Englefield Green in 1852; the former was killed. In both cases, the winners of the duels, Hawkey and Barthélemy, were tried for murder. But Hawkey was acquitted and Barthélemy was convicted only of manslaughter; he served seven months in prison. However, in 1855, Barthélemy was hanged after shooting and killing his employer and another man.

For those of us who like our romanticism, do no fret for it was only in 1994 that the most recent real duel occurred in Britain. At the appropriately named Battle in East Sussex, lutenist Ben Salfield reportedly fought against an unknown adversary with cavalry swords, over an insult allegedly made to a lady. The musician apparently won, and neither party suffered serious injury. He later recalled the incident as happening “on a hillside at dawn, dressed in 17th century clothes”, and described it as “a brutal but fair way to decide a matter of honour.

We could have a more recent duel still in the Brexit referendum when Polish businessman and aristocrat Prince Jan Zylinsky challenged Nigel Farage of the UK Independence Party to a duel. Showing uncharacteristic leanings towards modernity, Mr. Farage declined, preferring to settle the disagreement through political discussion.

Perhaps duelling continues today in the darker sides of gang violence. Not so much nobility but the same protecting of one’s honor from insult?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I think you are right. I guess that just as we don’t think much of such situations now, people back then felt the same about duels. Probably as long as two people want to fight each other, they will find a way whether it is legal or illegal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I liked your thoughts on “politeness”. It would probably be harder to be polite under distressful circumstances than to challenge to a fight. Regardless, wars between individuals or countries lay many in the grave for no good reason.

LikeLike

I’d like to see Nigel Farage have a duel. I think duelling makes for wonderful romantic fiction, and I love reading Alexandre Dumas’ works. In reality, it seems utterly absurd for people to behave in this way and I suppose the modern equivalent could be road rage 😡?

LikeLike

Thanks for an interesting post – I was particularly intrigued by the petticoat duels!

LikeLike

Informative and interesting. Thanks.

LikeLike

Informative and interesting, especially considering the many misconceptions people now have about this practice.

LikeLike