Going by the furore in the media at the moment, one would be forgiven for thinking that the world is ending because of the likelihood that Russia has hacked into American computer systems. The truth is, this sort of thing has been happening at least for many centuries if not since the dawn of civilisation.

Does anyone really believe that America and Russia haven’t hacked each before? China has almost built its current position on the backs of commercial hacking of industrial secrets and processes from western nations. Indeed it is only a few years ago since the big scandal over the American NSA bugging and monitoring German Chancellor Angela Merkel and her government, supposedly their strong allies.

GCHQ in Britain is possibly the number one intelligence gathering service in the world and the NSA in the United States even pay towards the service due to its perceived expertise. It is said that it was GCHQ that informed the CIA that Russia was hacking into American systems in the election campaign after fending off similar Russian attacks on our own election campaign in the previous year. To know of this, one would assume that Britain is also hacking Russia and the USA too. Which is no doubt often convenient seeing as the NSA is supposedly not allow to spy on its own citizens. This is nothing new however as we’ll see later in this post.

These days, hacking is primarily conducted electronically, using electronic communication systems that carry hopefully codified methods of communication. Apart from the electronic element, such codes or cyphers have been around much longer than many would imagine.

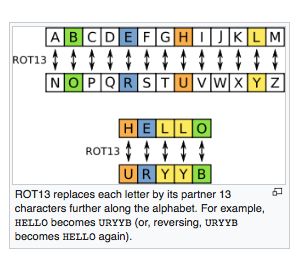

The Romans for one had various cyphers which are very weak by modern standards but at the time must have seemed impregnable. ROT 13 is a variety of the Ceasar cypher and works on a simple substitution method where the alphabet is divided into two groups of 13 letters. Each letter is simply swapped by the letter 13 letters removed.

Britain has a long tradition on cyphers and codebreaking. In the Elizabethan Era, Thomas Phelippes was in charge of monitoring the communications of those suspected of plotting against the queen. He is most famous for breaking the cypher letters between Mary Queen of Scots and Anthony Babington.

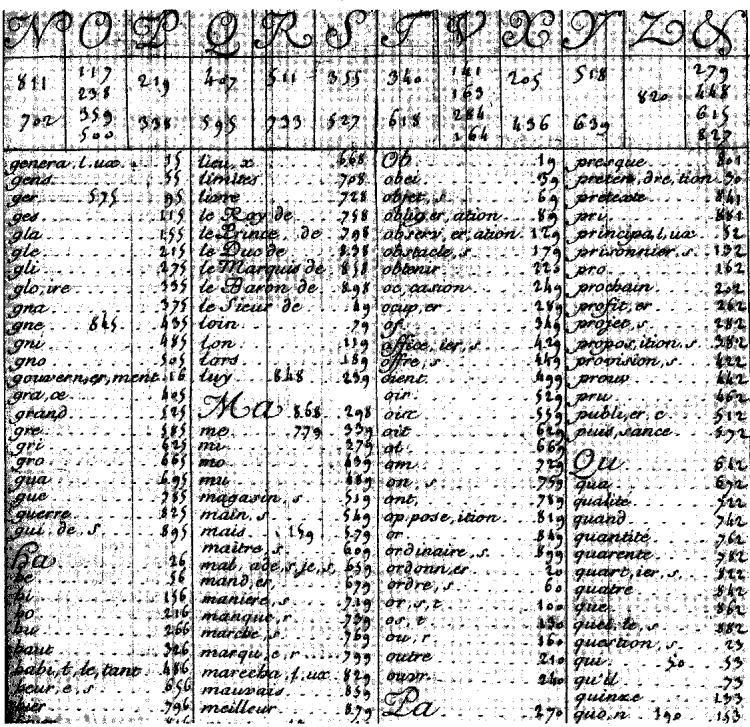

Centuries later, George Scovell led a team called the Army Guides. He was a brilliant linguist and he gathered together a group of individuals, each with their own often dubious gifts and managed to break the French code known as the Grande Chiffre which had been the mainstay of their communications for centuries.

In the spring of 1811, the French began using a code based on a combination of 150 numbers known as the Army of Portugal Code. Scovell cracked the code within two days. At the end of 1811, a new code called the Great Paris Code was sent to all French army officers. It was based on 1400 numbers and derived from a mid-eighteenth century diplomatic code (Grande Chiffre) which added meaningless figures to the end of letters. By December 1812, when a letter from Joseph Bonaparte to Napoleon was intercepted, Scovell could decipher enough of it to read Joseph’s explicit account of French operations and plans. The information gained proved vital to Wellington’s victory over the French at Vitoria on 21 June 1813.

It is no doubt actions such as this which in Iran has Britain known as the sly old fox, sneakily and cleverly manipulating events behind the scenes in a more dangerous or productive way than others might be by using outright force.

Of course apart from the theatrics of James Bond and the infamous hacking of the Engima Machine codes and indeed doing the opposite and ‘faking news’ through actions such as Operation Mincemeat.

Once less well known occurrence of historic hacking which had grander repercussions more likely than even Vladmir Putin could ever hope for is the case of The Zimmermann Telegram.

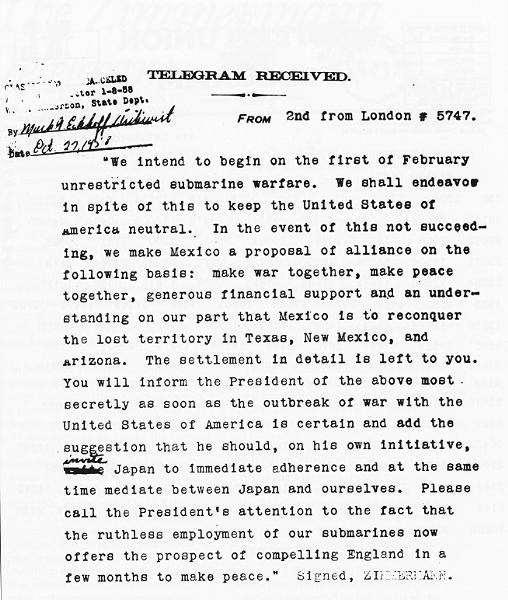

The Zimmermann Telegram, as it came to be known, was critical to the Americans entering the first world war, which was crucial for the Allies to gain victory. More than this, in January 1917, the efforts of the young codebreaking genius Nigel de Grey, and his eccentric colleagues, shaped the thinking of President Woodrow Wilson on America’s future role as a supremely powerful interventionist force that lasted until the present day.

An old Etonian by the name of Nigel de Grey who was then a 30-year-old Balloon Corps veteran transferred to the Admiralty intelligence department, would become one of the most senior figures at Bletchley Park during the second world war. He would also go on to have a vital role in constructing the modern post-war form of GCHQ. But the interception of the Zimmermann Telegram was a uniquely pivotal and indeed for many years a classified moment.

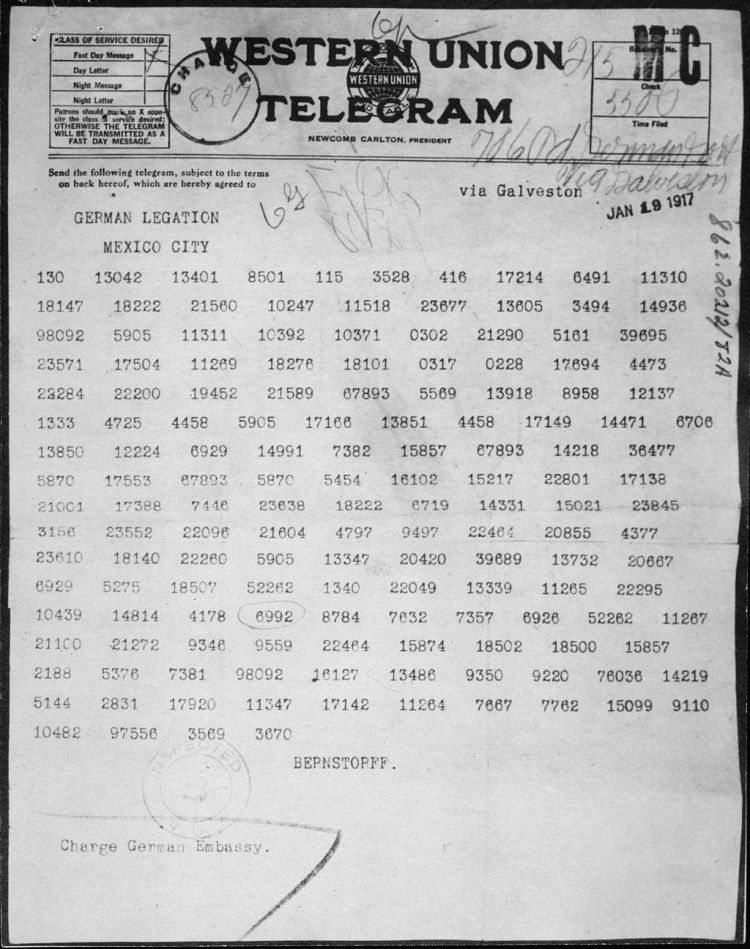

At the beginning of 1917, in the aftermath of the Somme and with the land war slogging bloodily on, the Germans planned a new and terrible submarine offensive in the Atlantic. The idea was to target all merchant shipping heading for Britain. No matter where they came from, cargoes and crews would be blasted into the dark icy depths. That even meant ships from America.

Even at this late point in WW1, America was doggedly pursuing its policy of neutrality. Aware that their new plans might not go down well in America, the German Foreign Minister, Arthur Zimmermann, got in touch with his ambassador in Mexico. Deciding that German many as well go the whole hog when upsetting the USA, Zimmermann wanted to encourage Mexico to attack America by promising Mexico the return of Texas. With Germany helping out with money and arms, the USA would be fighting on multiple fronts and its power diffused so less willing and able to help the British in Europe.

German telegraph cables across some parts of Europe had been cut but they could still send messages via circuitous neutral routes. One of the connecting cables, used by Americans, ran under a Cornish village prior to crossing the Atlantic seabed. The British codebreakers were secretly tapping it. And so it was that they got hold of the encoded message from Herr Zimmermann.

Back in a rather dusty corner of the Admiralty, Nigel de Grey and his team got to work. This department, Room 40, was the forerunner to Bletchley. Codebreakers then tended to be classicists rather than mathematicians. De Grey was rather brilliant on languages, but he also had the extra element of lateral-thinking genius rather like Sherlock Holmes is portrayed in the BBC show, Sherlock. One section of the department had — randomly — a large bath at the end of a corridor where his colleague Dilly Knox monopolised it, often sitting naked and quite still in the hot water, miles away in abstruse thought.

The German codes they were tackling were exquisitely complex, so much so that the Germans assumed they could never be cracked. This was some time before machinery could be involved to help break the codes. Instead and almost unbelievably, cryptology involved almost unimaginable mental gymnastics, plus blackboards and chalk.

Nonetheless, having got hold of the telegram, Nigel and his team decoded it in a couple of days. They instantly understood the importance of their discovery and rightly concluded that if the American president and the people could see this proof of German treachery in black and white then that would change everything. Whilst at worse, it was a very real possibility that Germany might fight the Allies to a standstill forcing the French to sue for peace and at best, an Allied victory might be years away, this hacking discovery was an unbelievable breakthrough.

De Grey himself described the scene when he took the find to his boss, Admiral William ‘Blinker’ Hall:

We had got a skeleton version, sweating with excitement because neither of us doubted the importance of what we had in our hands… As soon as I felt sufficiently secure in our version, even with all its gaps… I ran all the way to [Blinker’s] room… I burst out breathlessly, ‘Do you want America in the war, Sir?’ ‘Yes, why?’ said Blinker. ‘I’ve got a telegram that will bring them in if you give it to them.’

In Blinker’s version of the event, he referred to de Grey as ‘dear boy’.

That was only the beginning however as it was vital that the Germans did not twig that their codes had being broken on an industrial scale. At the other end, It was also vital that the Americans did not know that the British were tapping their cables, so it was made to look as though the cypher-snatch had happened in Mexico.

A few weeks later President Wilson, who had been so determined to keep the US out of the carnage, was presented with Zimmermann’s plot. There was initial scepticism, but the British codebreakers allayed it. The day before Zimmermann’s letter was made public to the press, President Wilson told colleagues: ‘If you knew what I know at this present moment, and what you will see reported in tomorrow morning’s newspapers, you would not ask me to attempt further peaceful dealings with the Germans.’

Publication brought conspiracy–theorist howls against the media. According to the historian Adam Tooze, an American–German activist called George Sylvester Viereck protested bitterly to newspaper proprietor William Randolph Hearst that ‘the alleged letter… is obviously a fake; it is impossible to believe that the German foreign secretary would place his name under such a preposterous document.’

Some weeks later, Arthur Zimmermann confessed that the message was real and America entered the war in April 1917.

Because of decades of official secrecy, the codebreaker who changed the future was never given a hint of public acknowledgement. It was only some years after his death that his brilliant work could be summoned from the shadows.

Curiously, in those interwar years, Nigel was quite forgotten about by the code-breakers of the Government Code and Cypher School, until the darkness of Nazism crept over. The Admiralty wrote to him in early 1939, asking if he had any sort of experience in the field of intelligence. Nigel’s sardonic reply brought a scramble of apologies and exhortations that he return to the cryptology fold. The business of codebreaking was so secret that even its own heroes could disappear. In fact very similar events happened at Bletchley after WW2 with Churchill orderi9ng the entire programme shut down and in doing so, gifting the embryionic world of computing to America.

Nigel de Grey was relatively small of stature — hence his nickname ‘the Dormouse’

Today, Nigel de Grey is one of the most revered names by the cryptanalysts of GCHQ in Cheltenham, themselves the successors to the geniuses of Bletchley Park. His part in establishing codebreaking as one of the most vital means of defending the realm now spans a century just as it looks like America may start pulling back from that global interventionist vision which he himself set in place.

If you’d like to know more about WW1 including sections on the new scientific inventions of the war, why not check out my easy to read history book on the First World War.

Fascinating stuff. Didn’t know anything about ww one and room forty

Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s amazing what went on back then. I think people wouldn’t be quite so alarmed at how things are today if they were more aware of how ‘these things’ have always happened.

LikeLike

Great and informative post as always, Stephen. It often makes me laugh how offended countries get when something like this happens because they/we are all as bad as each other. Much like with politicians, every country is run by conniving, deceitful and quite honestly scum of the earth sorts as a rule…and yet we all vote for them and they decide on policies and employ people to carry them out I suppose.

Maybe one day it will all change and everyone can jus be honest, communicate well and just get along!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad that you liked it. I think you absolutely right to a greater or lesser extent. Some of them are just cleverer or sneakier about it (Britain) and others just don’t care or get caught all the time (Russia) and everyone is the same. There was scandal a week ago as an Israeli embassy personnel was caught on film talking about bringing down a British minister and then they saying it was nothing serious and yet we all know all hell would break lose if someone did something similar there. I think we should just accept every country, like every person is self-interested to a certain degree and if countries like the UK and USA can mostly get by together then that is a huge bonus,

LikeLiked by 1 person