Yesterday marked the 50th anniversary of one of the worst post-war disasters in Britain when on an ordinary October day, a quiet village in South Wales literally had the world fall in on them.

The village of Aberfan sat beneath the spoil tips of the Merthyr Vale Colliery. Throughout the 20th century coal had been dumped on the hillsides above the village. The locals had long protested that they were unsafe but their concerns had been ignored. What had also been ignored was that the spoil heaps were much taller than the National Coal Boards own safety recommendations. The facts that the spoil was splace on such a steep slope and blocked natural springs meant that they were fundamentally unstable and sooner or later disaster was bound to strike.

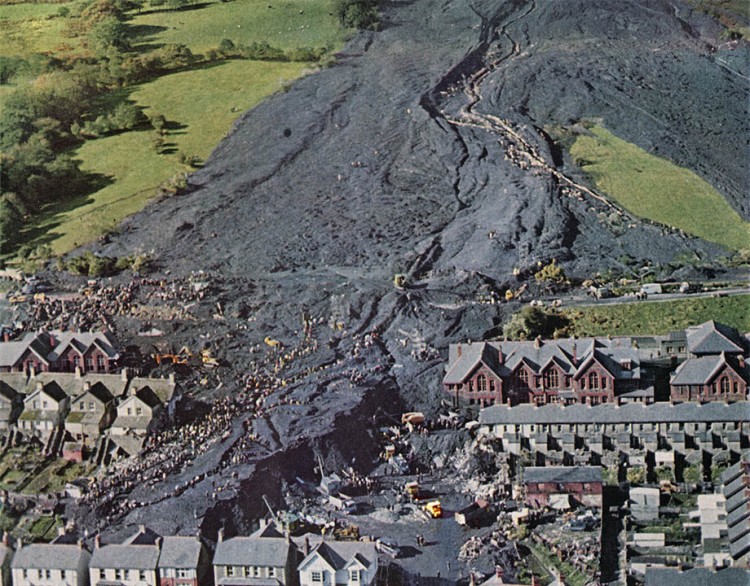

Early on the morning of Friday, 21 October 1966, after several days of heavy rain, a subsidence of approximately 10–20 feet (3–6 m) occurred on the upper flank of colliery spoil heap No. 7. At 9.15 am more than 150,000 cubic metres (5,300,000 cu ft) of water-saturated debris broke away and flowed downhill at high speed. It was sunny on the mountain but foggy in the village, with visibility only about fifty metres (160 ft). The tipping gang working on the mountain saw the landslide start but were unable to raise the alarm because their telephone cable had been stolen. The official inquiry later established that the slip happened so fast that a telephone warning would not have saved any lives.

The front part of the mass became liquefied and moved down the slope at high speed as a series of viscous surges depositing 4,200,000 cubic feet (120,000 cu metres) of debris on the lower slopes of the mountain. A mass of more than 1,400,000 cubic feet (40,000 cu metres) of debris slid into the village in a slurry 40 feet (13 m) deep.

The slide destroyed a farm and twenty terraced houses along Moy Road and struck the northern side of Pantglas Junior School and part of the separate senior school, demolishing most of the structures and filling the classrooms with thick mud, sludge and rubble up to 30 foot (10 metres) depth. Mud and water from the slide flooded many other houses in the vicinity, forcing many villagers to evacuate their homes. A huge mound of slurry blocked the northern end of Moy Road; lesser amounts reached Aberfan Road.

The pupils of Pantglas Junior School had arrived only minutes earlier for the last day before their October half-term holiday. The teachers had just begun to record the children’s attendance in the registers when a great noise was heard outside. They were in their classrooms when the landslide hit: there were heavy casualties in classrooms on the side hit.

Nobody in the village could see it, but everyone heard the roar of the approaching landslide. Some at the school thought a jet plane was about to crash and one teacher ordered his class to hide under their desks. Gaynor Minett, an eight-year-old at the school, later recalled:

It was a tremendous rumbling sound and all the school went dead. You could hear a pin drop. Everyone just froze in their seats. I just managed to get up and I reached the end of my desk when the sound got louder and nearer, until I could see the black out of the window. I can’t remember any more but I woke up to find that a horrible nightmare had just begun in front of my eyes.[12]

After the landslide there was total silence. George Williams, who was trapped in the wreckage, remembered:

In that silence you couldn’t hear a bird or a child.

After the main landslide stopped, frantic parents rushed to the scene and began digging through the rubble, some clawing at the debris with their bare hands, trying to uncover buried children. Police from Merthyr Tydfil arrived soon after and took charge of the search-and-rescue operations. As news spread, hundreds of people drove to Aberfan to try to help, but their efforts were largely in vain. Water and mud was still flowing down the slope, and the growing crowd of untrained volunteers hampered the work of trained rescue teams who were arriving. Hundreds of miners from local collieries rushed to Aberfan, especially from Merthyr Vale Colliery but also neighbouring collierys around the valleys. More men came from pits across the south Wales coalfield, many in open lorries with shovels in their hands, but by the time they reached Aberfan there was little they could do. A further threat was posed by a fresh torrent of water, released by two water mains, supplying the city of Cardiff, which had been fractured by the avalanche breaking through the old railway line embankment. The additional water flooded into the already saturated mounds of slurry. The flow of water was eventually stopped at 11.30 am.

A few children were pulled out alive in the first hour, but no survivors were found after 11 am.

– Alix Palmer on her first assignment for the Daily Express newspaper wrote to her mother….

By the next day, 2,000 emergency services workers and volunteers were on the scene, some of whom had worked continuously for more than 24 hours. Rescue work was temporarily halted when water began pouring down the slope again. Because of the vast quantity and consistency of the spoil, it was nearly a week before all the bodies were recovered.

The rain held off until teatime then started drizzling. By 7pm it was pelting down. One of the houses shattered by the avalanche was still burning. No-one had yet been found alive or dead from any of the ruined houses.

By this time, the slag had had time to corrode the skin of the children still buried and many brought out burned could only been identified by the clothing or things in their pockets. One little boy, whose father, a teacher at the school who had saved some of his son’s classmates, was identified by a slip of paper with his name on deep inside his wallet…

Men who had started digging at 9.30 the previous morning, were still digging, with shirts off and bodies sweating despite the cold.

I saw such dreadful things, Mummy. They brought out the deputy headmaster, still clutching five children, their bones so hardened that they first had to break his arms to get the children away then their arms to get them apart. And the mothers of two of them watched it happen.

I saw limbs brought out which bore no resemblance to human arm or leg, flesh burned away by this dreadful stuff, small children already beginning to decompose because there had been air-locks beneath the slag.

Just 250 yards from the disaster site, the tiny Bethania Chapel became a temporary mortuary and missing persons bureau from 21 October until 4 November 1966 and its vestry was used by Red Cross volunteers and St John Ambulance stretcher-bearers. The smaller Aberfan Calvinistic Chapel was used as a second mortuary from 22–29 October and was “the final resting-place for the deceased before interment.”

Two doctors examined the bodies and issued death certificates; the causes of death were typically asphyxia, or multiple crush injuries. Hundreds of embalmers were called to the village to prepare the battered bodies for identification by parents. To make a bad situation worse, the ramped conditions in the chapel meant that parents could only be admitted one at a time to identify the bodies of their children. One mother recalled being shown the bodies of almost every dead girl recovered from the school before identifying her own daughter.

The death toll was 144; among the dead were five teachers and 116 children between the ages of 7 and 10, equalling almost half the children on the Pantglas Junior School roll. Most victims were interred at Bryntaf Cemetery in Aberfan in a joint funeral on 27 October 1966, attended by more than 2,000 people

During the rescue operation, the shock and grief of parents and townspeople were exacerbated by insensitive behaviour from the media – one unnamed rescue worker recalled hearing a press photographer tell a child to cry for her dead friends because it would make a good picture. The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh visited Aberfan on 29 October to pay their respects to those who had died.The Queen received a posy from a three-year-old girl with the inscription: “From the remaining children of Aberfan“. Onlookers said she was close to tears.

Anger at the National Coal Board erupted during the inquest into the deaths of 30 of the children. The Merthyr Express reported that there were shouts of “murderers” as children’s names were read out. When one child’s name was read out and the cause of death was given as asphyxia and multiple injuries, the father said “No, sir, buried alive by the National Coal Board”. The coroner replied: “I know your grief is much that you may not be realising what you are saying” but the father repeated:

I want it recorded – “Buried alive by the National Coal Board.” That is what I want to see on the record. That is the feeling of those present. Those are the words we want to go on the certificate.

A social worker later noted that many people in the village were prescribed sedatives but did not take them when it was raining because they were afraid to go to sleep, and that surviving children did not close their bedroom doors for fear of being trapped. A doctor reported trauma emerged amongst the survivors with the local the birth rate went up, alcohol-related problems increased, as did health problems for those with pre-existing illnesses, and many parents suffered breakdowns over the next few years.

Many people suffered from the effects of guilt, such as parents who had sent children to school who did not want to go. Tensions arose between families who had lost children and those who had not. A surviving school child recalled that they did not go out to play for a long time because families who had lost children could not bear to see them, and they felt guilty that they had survived.

Chairman of the National Coal Board, Alfred Lord Robens, was a senior union official in the 1930s and a Labour MP who became Minister of Power in the final days of the Attlee Labour government. His actions immediately after the disaster and in the years that followed have been the subject of considerable criticism. When word of the disaster reached him, Robens did not immediately go to the scene but went ahead with his investiture as Chancellor of the University of Surrey. He did not arrive at the village until Saturday evening. NCB officers covered up for him when contacted by the Secretary of State for Wales, Cledwyn Hughes, falsely claiming that he was personally directing relief work when he was absent.

When he reached Aberfan, Robens told a TV reporter that nothing could have been done to prevent the slide, attributing it to natural unknown springs beneath the tip, a statement the locals challenged. The NCB had been tipping on top of springs that were clearly marked on maps of the neighbourhood, and where villagers had played as children.

Robens’ evidence to the Tribunal of Inquiry was unsatisfactory; so much so that the NCB’s counsel in its closing speech asked for Robens’ evidence to be ignored. Robens took a very narrow view of the NCB’s responsibilities regarding the remaining Aberfan tips. His opposition to doing anything more than was needed to make the tips safe, even after the Prime Minister had promised villagers the tips would have to go, was overcome only by a grant from the government and a bitterly opposed and much resented contribution from the disaster fund of £150,000, nearly 10% of the money raised.

The public demonstrated its sympathy by donating money with little idea of how it would be spent. Donations flooded in to an appeal initiated by the Mayor of Merthyr Tydfil and within a few months, nearly 90,000 contributions had been received, totalling £1,606,929 (£27.8 million in 2015, if adjusted for inflation). In fact money and donations flooded in from around the world and I remember my own mother telling me that she had posted one of her dolls to the village in the hope it would help one of rthe children there.

As a result of concerns raised by the disaster, and in line with the findings of the Davies Report, in 1969 the British government framed new legislation to remedy the absence of laws and regulations governing mine and quarry waste tips and spoil heaps and related laws which meant that disused mines and spoil were not to be left to be injurous to members of the general public. In fact it went on to inspire the famous Health & Safety at Work Act 1974 which generally states that all employers have a duty “to conduct his undertaking in such a way as to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that persons not in his employment who may be affected thereby are not thereby exposed to risks to their health or safety.”

Merthyr Vale Colliery closed in 1989. In 1997 the incoming Labour government of Tony Blair returned the £150,000 it had been induced to pay by the Labour government of Harold Wilson, towards the cost of tip removal, to the disaster fund. No allowance was made for inflation or the interest that would have been earned over the intervening period.

The disaster was remembered yesterday with a minute silence across Wales and remembrance across the United Kingdom. Prince Charles led a memorial at Aberfan where he delivered a sombre message of rembrance and soldarity from The Queen.

Indeed. The same occurred in China as they piled up construction wastes – ie the earth dug from all that construction. This pile came crashing on the town that it towered over! Indeed we must remember these days of tragedy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I remember the Chinese accident. Let’s hope that in the future those in power value human life enough to at least take precautions to stop preventable accidents.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A terrible event indeed. I remember it well at school.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a bit before my time but one of those events that obviously haunted everyone who witnessed it on television.

LikeLike

A terrible tragedy. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re welcome Merril. I hope you are keeping well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Stephen, and I hope you are, too. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Pete's Favourite Things and commented:

I was 8 when this occurred and I still remember watching the pictures on TV with horror

LikeLiked by 1 person

Remember this well. A great sadness for Wales that reverberated around the world.

LikeLike

Dear God. That is hideous!

LikeLike

Things like this cannot ever be forgotten especially for the memory of those who died. It is worse when so many children lose their lives.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing this deeply moving story. My partner and I read it together. Moved to tears many times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a tragic story – thank you for sharing it in such a thoughtful manner. I read this post a couple of days ago and it has stayed on my mind. Just devastating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And this was in 1966.

Not 1866, or 1766, but the year England won the World Cup.

I vaguely remember it. I was only 4 or 5 at the time, but it was something I grew up knowing about, growing up in a valleys market town half way between Cardiff and Merthyr Tydfil.

This is the best and most detailed account I have seen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed the account of this terrible tragedy. It must have been one of those awful things that cast a shadow over everyone like Hillsborough or the Jamie Bulger murder, especially with it being quite local.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is still upsetting and makes me a bit angry, how people could have piled the slurry and mining spoils above a village school like that. 116 children. well done for making the facts public.

The Rhondda valleys are very green now. As the mining phased out, the black, faux mountains of coal spoils that grew up were built with internal supports and grass and trees planted. When I was a kid in the ’60s and ’70s, driving up to see my mother’s mother, it was very steep and everything was black. Now it’s all green again, but they say not as beautiful as before the mining came.

And the hills have that odd, man-made shape about them!

LikeLike