Today is the 950th anniversary of one of the most pivotal battles in history. Perhaps only the Battle of Manzikert in 1071AD which saw the collapse of the Byzantine Empire and the gradual Turkification of Anatolia can rival it for at least a century before or after.

The lead up to the Battle of Hastings is as long and complex as the impact of the battle was far-reaching. Previously England was ruled by Edward The Confessor who being an extremely pious and religious man, also became known as Saint Edward The Confessor and he was the last of the Wessex Kings, ruling from 1042 to 1066.

Edward had no children, following his pious pledge that he made before marriage and so the question of succession was and is a complicated one. Edward had quite a complex familial relationship and though he was King of England, there were many other powerful figures vying for power. It is certainly possible that the Norman claim that William of Normandy met with Edward at some point and that possibly, Williams was promised the throne but it does seem more likely on balance that the nobleman Harold Godwinson had been promised the throne.

Things get more complicated because in 1064, Harold found himself shipwrecked in Normandy, for reasons that aren’t fully known. It is likely that he was blown off course and captured on the coast. It is said by the Normans that during Harolds stay in Normandy, that he promised William the throne of England, possibly in return for his release and safe return to England. In either event, William must have been mistaken as the Anglosaxon kings were not chosen by succession or by the then ruling monarch, instead the Witenagemot, the assembly of the kingdom’s leading notables, would convene after a king’s death to select a successor.

England was already in turmoil as Harolds brother, Tostig, ruled the powerful area of Northumbria and had been doing a terrible job, causing the people to rebel against him to the extent that Harold sided with the rebels and took power away from his own brother. It is likely that this sealed the deal and Edward saw Harold as the best successor with a sense of political sophistication and intelligence that supplemented his strong physical presence and well known bravery on the field of battle.

After Edward died, Harold became King of England on 6th January 1066 as the Witenagemot had been guided by some of Edwards last words when he emerged from a coma before mentioning Harold.

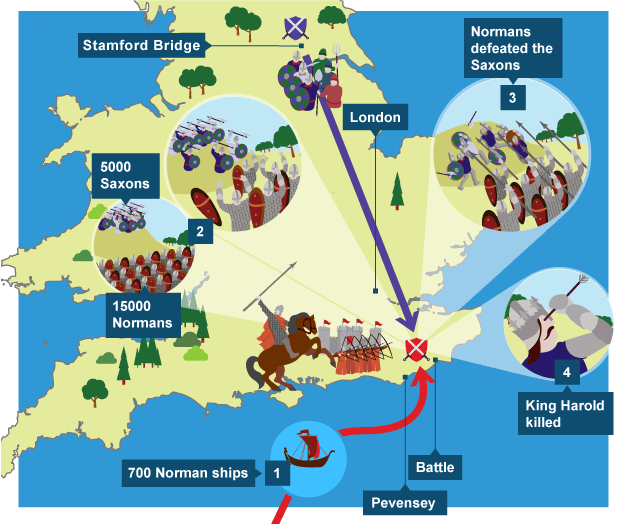

William of Normandy (sometimes known as William The Bastard due to his family situation) immediately set about creating a vast invasion fleet of 700 ships though it took some time to get any support and it is likely he lied when he stated that Harold had sworn on holy relics that William himself should become king; nevertheless it was effective in getting important church support.

Kind Harold wasn’t stupid and he had assembled an army on the Isle of Wight, just off the southern coast of England. However due to Williams problems at assembling an army and also to a long period of unfavourable winds, no invasion came. On 7th September 1066, Harold disbanded his non-professional army, he returned to London and his men went back to their homes to do the most important job in the kingdom, to harvest the crops and prevent starvation.

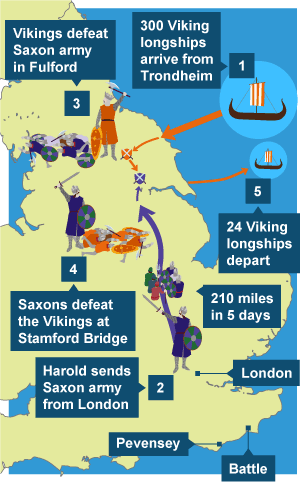

On that very same day, King Harald Hardrada (or hard ruler) of Norway landed at Tynemouth near the city of Newcastle in Northumbria. He had formed an alliance with Harolds disaffected brother Tostig and claimed the English crown as his own.

The invading forces of Hardrada and Tostig defeated the English earls, Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria, at the Battle of Fulford near York on 20 September 1066. Harold having led his army north on a forced march from London in four days and having caught them by surprise. According to Snorri Sturluson, before the battle a man bravely rode up to Harald Hardrada and Tostig and offered Tostig his earldom if he would but turn on Harald Hardrada. When Tostig asked what his brother Harold would be willing to give Harald Hardrada for his trouble, the rider replied that he would be given seven feet of ground as he was taller than other men. Harald Hardrada was impressed with the rider and asked Tostig his name. Tostig replied that the rider was none other than Harold Godwinson.

On 25th September, King Harold won the epic Battle of Stamford Bridge. 15,000 English defeated 9,000 invaders and the battle is renowned for its savagery with 5,000 English dead and 6,000 Scandinavians. It had been one of the most fantasic English victories of all time with a feared ‘Viking’ army being all but wiped out, indeed of the 300 Longships that came to England, only 24 were needed to carry off the survivors.

In any other time, this would have been one of the most noted dates in history and King Harold would have been lauded like few others but then just 3 days later and at the most inconvenient and unlucky time imaginable, William of Normandy and his forced landed on the south coast at Pevensey on 28th September. England was facing a second invasion at the other end of the country.

After defeating his brother Tostig and Harald Hardrada in the north, Harold left much of his forces in the north, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest of his army south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion. It is unclear when Harold learned of William’s landing, but it was probably while he was travelling south. Harold stopped in London, and was there for about a week before Hastings, so it is likely that he spent about a week on his march south, averaging about 27 miles (43 kilometres) per day,for the approximately 200 miles (320 kilometres). Harold camped at Caldbec Hill on the night of 13 October, near what was described as a “hoar-apple tree”. This location was about 8 miles (13 kilometres) from William’s castle at Hastings. Some of the early contemporary French accounts mention an emissary or emissaries sent by Harold to William, which is likely. Nothing came of these efforts.

Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William’s scouts reported the English arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy.Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill(present-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 miles (9.7 kilometres) from William’s castle at Hastings

Though Norman figures put the English army as numbering up to 1.2million, it seems pure propaganda and it is likely that around 7-8,000 Englishmen came up against around 14-15,000 Normans. That the English made it at all is quite remarkable given the months spent on the Isle of Wight and then the 300 mile march up to fight Hardrada with a savage all day battle followed by an exhausting march back past London to the south coast.

Because many of the primary accounts contradict each other at times, it is impossible to provide a description of the battle that is beyond dispute.The only undisputed facts are that the fighting began at 9 am on Saturday 14 October 1066 and that the battle lasted until dusk. Sunset on the day of the battle was at 4:54 pm, with the battlefield mostly dark by 5:54 pm and in full darkness by 6:24 pm. Moonrise that night was not until 11:12 pm, so once the sun set, there was little light on the battlefield. William of Jumieges reports that Duke William kept his army armed and ready against a surprise night attack for the entire night before.The battle took place 7 miles (11 km) north of Hastings at the present-day town of Battle, between two hills – Caldbec Hill to the north and Telham Hill to the south. The area was heavily wooded, with a marsh nearby.The name traditionally given to the battle is unusual – there were several settlements much closer to the battlefield than Hastings. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle called it the battle “at the hoary apple tree”. Within 40 years, the battle was described by the Anglo-Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis as “Senlac”, a Norman-French adaptation of the Old English word “Sandlacu”, which means “sandy water”.This may have been the name of the stream that crosses the battlefield. The battle was already being referred to as “bellum Hasestingas” or “Battle of Hastings” by 1087, in the Domesday Book.

Sunrise was at 6:48 am that morning, and reports of the day record that it was unusually bright.The weather conditions are not recorded.The route that the English army took to the battlefield is not known precisely. Several roads are possible: one, an old Roman road that ran from Rochester to Hastings has long been favoured because of a large coin hoard found nearby in 1876. Another possibility is a Roman road between London and Lewes and then over local tracks to the battlefield.Some accounts of the battle indicate that the Normans advanced from Hastings to the battlefield, but the contemporary account of William of Jumieges places the Normans at the site of the battle the night before.

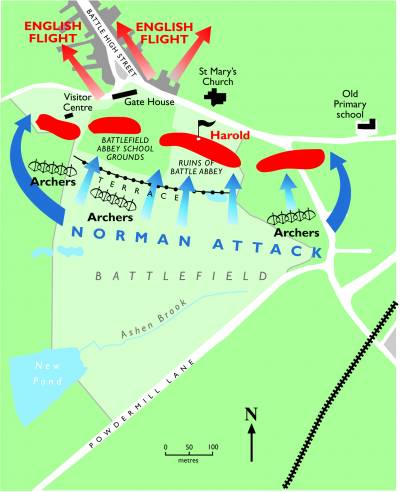

Harold’s forces deployed in a small, dense formation at the top of steep slope,[ with their flanks protected by woods and marshy ground in front of them.The line may have extended far enough to be anchored on a nearby stream. The English formed a shield wall, with the front ranks holding their shields close together or even overlapping to provide protection from attack. Sources differ on the exact site that the English fought on: some sources state the site of the abbey but some newer sources suggest it was Caldbec Hill.

More is known about the Norman deployment. Duke William appears to have arranged his forces in three groups, or “battles”, which roughly corresponded to their origins. The left units were the Bretons, along with those from Anjou, Poitou and Maine. This division was led by Alan the Red, a relative of the Breton count.The centre was held by the Normans, under the direct command of the duke and with many of his relatives and kinsmen grouped around the ducal party.The final division on the right consisted of the Frenchmen,along with some men from Picardy, Boulogne, and Flanders. The right was commanded by William fitzOsbern and Count Eustace II of Boulogne. The front lines were archers with a line of foot soldiers armed with spears behind. There were probably a few crossbowmen and slingers in with the archers.The cavalry was held in reserve and a small group of clergymen and servants situated at the base of Telham Hill was not expected to take part in the fighting.

William’s disposition of his forces implies that he planned to open the battle with archers in the front rank weakening the enemy with arrows, followed by infantry who would engage in close combat. The infantry would create openings in the English lines that could be exploited by a cavalry charge to break through the English forces and pursue the fleeing soldiers.

The battle opened with the Norman archers shooting uphill at the English shield wall, to little effect. The uphill angle meant that the arrows either bounced off the shields of the English or overshot their targets and flew over the top of the hill. The lack of English archers hampered the Norman archers, as there were few English arrows to be gathered up and reused.After the attack from the archers, William sent the spearmen forward to attack the English. They were met with a barrage of missiles, not arrows but spears, axes and stones.The infantry was unable to force openings in the shield wall, and the cavalry advanced in support.The cavalry also failed to make headway, and a general retreat began, blamed on the Breton division on William’s left. A rumour started that the duke had been killed, which added to the confusion. The English forces began to pursue the fleeing invaders, but William rode through his forces, showing his face and yelling that he was still alive.The duke then led a counter-attack against the pursuing English forces; some of the English rallied on a hillock before being overwhelmed.

It is not known whether the English pursuit was ordered by Harold or if it was spontaneous. Wace relates that Harold ordered his men to stay in their formations but no other account gives this detail. The Bayeux Tapestry depicts the death of Harold’s brothers Gyrth and Leofwine occurring just before the fight around the hillock. This may mean that the two brothers led the pursuit. The Carmen de Hastingae Proelio relates a different story for the death of Gyrth, stating that the duke slew Harold’s brother in combat, perhaps thinking that Gyrth was Harold. William of Poitiers states that the bodies of Gyrth and Leofwine were found near Harold’s, implying that they died late in the battle. It is possible that if the two brothers died early in the fighting their bodies were taken to Harold, thus accounting for their being found near his body after the battle. The military historian Peter Marren speculates that if Gyrth and Leofwine died early in the battle, that may have influenced Harold to stand and fight to the end.

Although the feigned flights did not break the lines, they probably thinned out the housecarls in the English shield wall. The housecarls were replaced with members of the fyrd, and the shield wall held. Archers appear to have been used again before and during an assault by the cavalry and infantry led by the duke. Although 12th-century sources state that the archers were ordered to shoot at a high angle to shoot over the front of the shield wall, there is no trace of such an action in the more contemporary accounts. It is not known how many assaults were launched against the English lines, but some sources record various actions by both Normans and Englishmen that took place during the afternoon’s fighting. The Carmen claims that Duke William had two horses killed under him during the fighting, but William of Poitiers’s account states that it was three.

Harold appears to have died late in the battle, although accounts in the various sources are contradictory. William of Poitiers only mentions his death, without giving any details on how it occurred. The Bayeux Tapestry is not helpful, as it shows a figure holding an arrow sticking out of his eye next to a falling fighter being hit with a sword. Over both figures is a statement “Here King Harold has been killed”.It is not clear which figure is meant to be Harold, or if both are meant.The earliest written mention of the traditional account of Harold dying from an arrow to the eye dates to the 1080s from a history of the Normans written by an Italian monk, Amatus of Montecassino.William of Malmesbury stated that Harold died from an arrow to the eye that went into the brain, and that a knight wounded Harold at the same time. Wace repeats the arrow-to-the-eye account. The Carmen states that Duke William killed Harold, but this is unlikely, as such a feat would have been recorded elsewhere. Harold’s death left the English forces leaderless, and they began to collapse.Many of them fled, but the soldiers of the royal household gathered around Harold’s body and fought to the end. The Normans began to pursue the fleeing troops, and except for a rearguard action at a site known as the “Malfosse”, the battle was over.Exactly what happened at the Malfosse, or “Evil Ditch”, and where it took place, is unclear. It occurred at a small fortification or set of trenches where some Englishmen rallied and seriously wounded Eustace of Boulogne before being destroyed by Duke William.

William was unable cross the Thames as he moved up country during the coming weeks and instead went in a very roundabout way to the small town of Berkhamsted where he officially accepted the surrender of the Anglo Saxon nobility including Edgar. Berkhamsted however was not high profile enough for William to be coronated and he entered the city of London and in a coronation ceremony at Westminster Abbey the magnificent church of Edward The Confessor, he was proclaimed King on Christmas Day 1066.

The Norman duke, on the other hand, was at the end of a very long and uncertain supply chain, isolated in hostile territory. Anything less than a knockout blow at Hastings could have been fatal to his plans, and perhaps to him, too.

Had Harold survived and won, He would have defeated mighty enemies in pitched battles at opposite ends of the country within weeks of each other: quite a feat. Indeed, we might well be talking of King Harold the Great, and perhaps of the great dynasty of the Godwinsons. It is likely that he would probably be celebrated today as one of England’s greatest warrior kings, on a par with Alfred The Great, Richard Lionheart and Edward I, and indeed the almost forgotten Æthelstan – we would probably pay much more attention to the earlier English kings without the artificial break provided by the Conquest.

Rather than be celebrated, the Battle of Hastings should really be remembered as the disaster it was. For it brought to an end the long and enlightened run of Anglo-Saxon supremacy in the kingdoms that eventually unified to become England. Almost there entire generation of leading English soldiers, lords and leaders were slaughtered on the battlefield. After much of the north of England refused to cower to Norman rule, the area was savagely and systematically ruined, depopulated and destroyed in what came to be known as The Harrying Of The North.

England and soon the rest of the British Isles were soon dominated by fantastic castles and military fortications but they were not defences against foreign invaders but rather as instruments of internal repression to allow a very tiny minority to savagely control a beaten people who had lost both their leaders and their men.

William The Conquerer adopted an absolutist approach to monarchy, one entirely different to which England had been used to. He catalogued every asset, person, animal and parcel of land in his infamous Domesday Book. Almost the entire country, well around 92%, was taken away from its rightful owners and re-distributed to Williams most loyal supporters. In fact though over 200 landowners who held their estates thanks to to the Norman king, only 2 were Anglo Saxons.

The long and very entrenched English traditions and movements towards freedom and democracy were put on hold for a number of centuries. People were no long equal before the law. Society was re-classified with men being compelled to work on their lord’s estates and unable to even leave home without his permission. Personal liberty and free-trade were put on hold. In short it the Normans brought everything that wasn’t English.

The language of England began to change, taking on many French terms and losing its splendid Germanic and Scandinavian language which only held on in parts of Scotland and northern Englan and even then in a much-reduced form.

The Normans themselves had been of Scandinavian stock and they have subjucated Normandy and much of France as effectively as they had England. They had only lived in France for a generation or so but they embraced the French language and traditions as their own, likely as part of a massive civilising effect having given up on their Norse practices. French was made the official language of the ruling elite and whereas Anglo-Saxons would use words like cow, pig and sheep, the Normans put us English in our place by using words such as beef, pork and mutton to describe the cooked food itself.

Orderic Vitalis who was a 12th century chronicler wrote “The English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off a yoke that was so intolerable and unaccustomed”.

The idea of us remaining under Norman influence continued for centuries with the Parliamentarians in the Civil War explaining how the landed gentry were “William’s lieutenants” who only had their position due to stealing the land from the rightful owners. Indeed even today, a vast percentage of land and wealth and positions of high status are held by descendants of the tiny minority who seized control of England in October 13th 1066 and in some ways, still control it today.

The Battle of Hastings is important in countless ways not just to those of us in the U.K and it being last time a foreign foe conquered our country but also for the way it shaped our relationship with Europe and the way that the new Norman elite played such an important role in creating a nation that would go to shape the entire world.

Nicely covered Stephen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank-you! So glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I co-wrote a three part teleplay based on these events – not taken up by the Beeb unfortunately – but I am still fascinated by the events, the period, the aftermath, and just how different things would have been had they been defeated at Hastings. I’ve been working on a blog about how the Norman (and Breton, etc.) success eventually brought us the King Arthur legend as we known it, so things would have been different there too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic recount! An intriguing “what if”. Imagine how English Kings (who spoke French) would not have had possessions in France ‘dominating’ it during the hundred years’ war.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, things would have been totally different. I think it is often forgotten that apart from the Norman elite, most English people were as oppressed as the Irish or Scottish too (who were also led by those with Viking blood in them). It must have been a awful moment for the AngloSaxons when they realised what happens and similarly a moment of incredible opportunity to the surviving Normans who had an entire country at their feet.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s right, in a way the oppression can be seen in how old English evolved over time. There are still Scandinavian roots in modern English but that is now less pronounced.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent as usual, Stephen. The Battle of Hastings is one of my favourites!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Malla. It is hard to condense everything into a single post. 1066 could almost be a blog on its own!

LikeLike