Charles “Monte Carlo” Wells was the only son amongst 3 sibling daughters and was born into a respectable family in Broxbourne, Hertfordshire before his family moved to Marseille in France.

Charles Wells certainly had an interesting life and not always in a good way. He worked in a sugar beet factory in the Ukraine and also in a Spanish lead mine before in 1868 he invented and patented a way to regulate the motion of ship propellers, an invention that earned him 5,000 Francs.

Around 1879, Charles moved to Paris where he created possibly the first ever Ponzi scheme by duping investors to park with their money as part of a bogus railway construction in the Calais region of France. Fleeing with their money, Charles Wells was later apprehended and received the first of 6 prison sentences.

Leaving prison, Charles Wells returned to the U.K. where he persuaded many to part with money in support of his inventions. The bizarre gadgets he came up with over the years included a musical skipping rope, which proved a popular toy, with versions of it still available today. But he failed to get very far with other innovations including a ‘combined walking stick and shopping trolley’ and a ‘device for cleaning ships’ bottoms when under way’.

However there is no evidence that any of these inventions were earth shattering and one individual is said to have lost over £1million in todays money.

A wealthy spinster named Caroline Phillimore, who was typical of those taken in by claims, visied his business premises near London’s Regent’s Park that boasted a chemical laboratory, machine workshop, and other state-of-the art wizardry needed for inventions such as a device to cut the amount of fuel used in steamships by 40 per cent.

In reality, the building consisted of nothing more than a few shabby offices. And on the surprisingly rare occasions that his unfortunate victims chanced by to inspect this technological wonderland, they were fobbed off by a clerk who had been given a magazine to copy out whenever visitors were around — presumably to give the impression that some kind of business was being carried on.

Skilfully stringing his dupes along — even building their trust by sending them his bank passbook to assure them he was running a successful operation — Wells might have continued in this lucrative vein had it not been for a dramatic shift in his personal life.

Appalled at her husband’s shady new business venture, his wife left him and returned to France with their daughter, and in 1890 he met a beautiful young artists’ model named Jeannette Pairis, the woman who would prove both his obsession and his downfall.

At 21, Jeannette was almost 30 years his junior, and Wells was utterly captivated by her dark eyes, pouting mouth, and plaited chestnut hair, which fell to her waist.

Despite his ill-gotten wealth, he had always been happy to potter around in a threadbare old suit and dine on such simple fare as boiled eggs. But Jeannette loved champagne, jewellery and expensive clothes, and the rest of his life would be devoted to meeting her extravagant demands.

Determined to please and impress her, he acquired an old cargo ship called the Tycho Brahe, and planned to turn it into the seventh largest yacht in the world, a luxurious floating palace with a ballroom big enough for 60 people to be entertained in comfort.

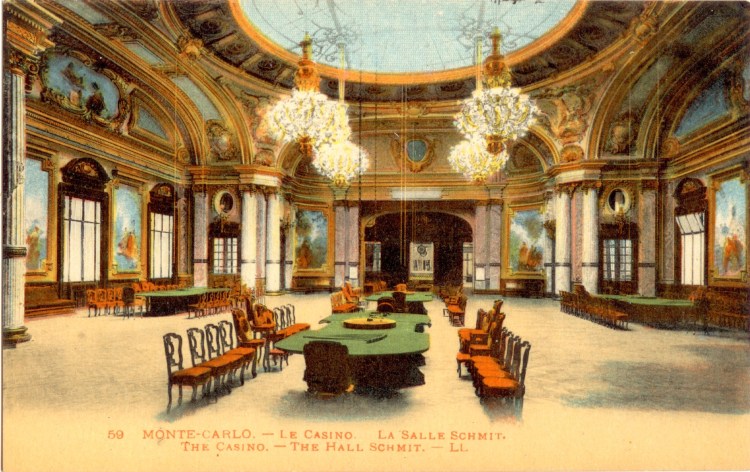

And it was to fund this costly venture that he arrived at the Casino de Monte-Carlo in the summer of 1891.

He was by no means the only individual to break the bank there, or even the first. In March 1891, only weeks before Wells became famous, one visitor had won £7,000 (worth £700,000 today) and an anonymous English nobleman scooped £10,000 (£1 million today) not long afterwards.

But what set Wells apart was that he repeated the trick so many times. So how did he do it?

We cannot rule out pure luck. But the likelihood of anyone repeating his feat is extremely remote and what we know about Wells’ wiliness suggests he would never have trusted good fortune alone.

His own explanation was that he had an infallible gambling system but unsurprisingly, he declined to say what it was but reporters dispatched to Monte Carlo as news of his remarkable winnings spread, could detect no obvious pattern in his placing of bets.

With his background, it seems more likely that this claim was an attempt to hide the fact that he was cheating and that as an engineer, he would have been aware that roulette wheels at the time often had mechanical flaws which resulted in certain numbers coming up more often than others.

By working out which numbers those were, he could have nudged the odds in his favour.

The only flaw in this theory is that the Casino de Monte-Carlo made regular checks to see which wheels were ‘true’, and removed faulty ones for immediate repair. Is it possible that its director, a distinguished-looking 45-year-old named Camille Blanc, have actively colluded with Wells to let him keep winning?

Watching from his spy-hole above the gaming floors, Blanc knew that customers who broke the bank were actually good for business, generating publicity which attracted many more gamblers to the casino.

Indeed, he had ensured that there was great drama around these events by inventing a ceremony enacted by his staff whenever the bank was broken. As the table in question was temporarily closed down, a black crepe cloth was spread over it with all the pomp of a state funeral.

There it remained until, after a decent interval, play was allowed to resume. By that point, there would be a crush of eager punters, all praying the table would prove similarly lucky for them.

Such stunts were needed more than ever at the time that Charles Wells broke the bank.

In 1863, Camille Blanc’s father Francois had been given the exclusive rights to run the casino, in return for meeting all the public expenses of the principality, including the costs of its roads, schools, hospitals and police.

This meant that the principality’s ruler Prince Charles III of Monaco would henceforth enjoy a rich lifestyle, and his people would never again have to pay any taxes. But he had died in 1889 and his heir Prince Albert had since declared a moral objection to deriving income from the losses other people made in the casino.

With the business under threat of being closed, Camille Blanc needed to wring every last drop of profit out of it. And given that Wells had once lived in Nice — only 14 miles from Monaco — and had at one point worked for one of Blanc’s relatives, it certainly seems feasible that they might have met to work out a strategy, with Wells as frontman.

One possibility is that Blanc arranged for Wells to sit at a roulette table with a biased wheel. And the card games would have been even easier to fix since, with a little sleight of hand, the management could arrange for the cards to come out in any order.

What’s more, as was entirely predictable, other customers soon began copying Wells’ every move and, with great crowds gathered around the table and placing bets on the same number or card, it would only take a few wins to swallow up the ‘bank’.

The evidence for this conspiracy is purely circumstantial, but there is no doubt that Charles Wells’ astonishing run of ‘luck’ in Monte Carlo benefited Camille Blanc considerably. With the public pouring into the casino in their thousands, and further boosting the royal fortunes, he and Prince Albert managed to patch up their differences and the casino was allowed to remain open.

Within two years the Blanc family’s 87 per cent stake in the business had risen by about £120 million in today’s values.

As for Charles Wells, his success at the gaming tables proved rather more double-edged.

Although his winnings enabled him to afford the complete refurbishment of his ship the Tycho Brahe, with the uniforms of the 18-man crew costing £10,000 apiece in today’s money, there was never any satisfying his beloved Jeannette’s demands for luxury and excess. He lived out his days engaged in a series of money-spinning scams, adopting some 43 aliases and serving a number of lengthy prison sentences along the way.

Not that any of this ever diminished his reputation in the eyes of the British public.

Although he had embezzled money from a wide cross-section of people, including a labourer from Liverpool who lost his life savings to one of Wells’ fraudulent schemes, they preferred to think of him as someone who had taken only from the rich, and never more spectacularly than when he beat the ‘system’ in Monte Carlo.

During his first in 1893, crowds gathered outside Wormwood Scrubs prison one bank holiday and serenaded him with choruses of the song which had made him famous. He delighted in their adulation. Soon afterwards, he was transferred to Portland Prison in Dorset and just before his release six years later it was his turn to perform.

A talented organist who played during services in the prison chapel, he led a sing-a-long of The Man Who Broke The Bank during his last appearance there.

He concluded that impromptu concert with Home Sweet Home, another popular song of the time —yet domestic bliss was something he never achieved.

In 1910, under an assumed name of Lucien Rivier, Charles opened up a new bank in Paris promising depositers interest rates of 365%. He was inundated with naive and greedy investors whose ever increasing numbers he used to pay back earlier investors. By doing this, Charles Wells conned his clients out of over £7million, an absolutely incredible money for Edwardian times. In 1912, his world finally came crashing down when French police put out a warrant for his financial irregularities and he was located in Britain and stood trial in Paris where he was sentenced to 5 years in prison.

Although he remained with Jeannette Pairis until his death from a heart condition in 1922, they were by then living in lodgings in London, and Wells died owing two weeks’ rent. Since Jeannette was unable to afford a headstone, she had no choice but to consign him to an unmarked pauper’s grave.

These days, as much as Charles Wells is remembered at all, it is for the catchy Victorian Music hall ding dong The Man Who Broke The Bank At Monte Carlo. Written in 1891 by Fred Gilbert, it was popularised by Charles Coburn who bought the song for £10 and performed it over 250,000 times in multiple languages around the world for the next 50 years. It quickly became a smash hit and entered popular culture, Peter O’Toole even sings it in Lawrence of Arabia.

It’s well worth a listen to hear a 125 year old song performed by quite a star who absolutely adored the chorus and I must say that after singing it about a dozen times, I agree. There are two references that modern listeners may not be familiar with. A Sou is a French term for a gold coin. Rhino was an extremely popular English expression for money that was popularised at least as far back as 1620 and related to the equally bizarre expression of paying through the nose. However, Rhino’s were not then known in Western Europe and it is likely the term originates from the 14th century saying of Ready Money or Readies. When the first Rhinos arrived in London the late 17th / early 18th century they were showcased as a curiosity to make money in a Ludgate pub and so strengthening the slang reference of rhino meaning money making the use of the word go full circle!

For more information on the extraordinary true story of Charles Wells, I’d encourage everyone to read the wonderful new biography written by Robin Quinn. It really is a great read and you can visit his website at http://www.robin-quinn.co.uk or visit his publishers at http://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/publication/the-man-who-broke-the-bank-at-monte-carlo/9780750961776/

Hi Stephen, I was interested to read all about your books on your website, and to read your blog. I was especially delighted to see that you had given some coverage to ‘The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo’. I’m the author of his biography, and the coverage is most welcome. It would be much appreciated if you could please add a link to my website, http://www.robin-quinn.co.uk, or to the page on my publisher’s website: http://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/publication/the-man-who-broke-the-bank-at-monte-carlo/9780750961776/

I’d be pleased to place a link to your website on mine, if you are happy for me to do so.

All best wishes, Robin Quinn

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Robin, I’m so glad you enjoyed my blog post and I hope you like the look of my books. I’ve added both your links to the bottom of the article. I get a steady run of readers to it so hopefully it will be at least a small help! It would be really nice if you could link to mine too. Many thanks, Stephen Liddell

LikeLike

Hi Stephen, many thanks for your kind words about my book on the man who broke the bank. Things have been hectic lately, but I’ve now mentioned your excellent website in my blog and added a link to it. (http://www.robin-quinn.co.uk/a-mine-of-information)

All best wishes, Robin

LikeLike