There have been lighthouses around the coasts and islands of Great Britain almost as far back there have been people travelling by ship. A fine Roman lighthouse of nearly 2,000 years is still standing tall within the walls of Dover Castle. The history of lighthouse keepers are as fascinating and treacherous as the often rough seas that have seen countless ships and their crews lost forever on rocky islets and hidden sandbanks.

It obviously took a special sort of person to be a lighthouse keeper for what was a lonely and dangerous profession. Many, many people have lost their lives or been driven to the point of insanity by the loneliness and poor conditions. For centuries lighthouses were operated by private business organisations and lighthouse keepers never really had any guarantee that they hadn’t been forgotten about or would ever be relieved of duty. If the business had collapsed then who would care to finance a rescue attempt?

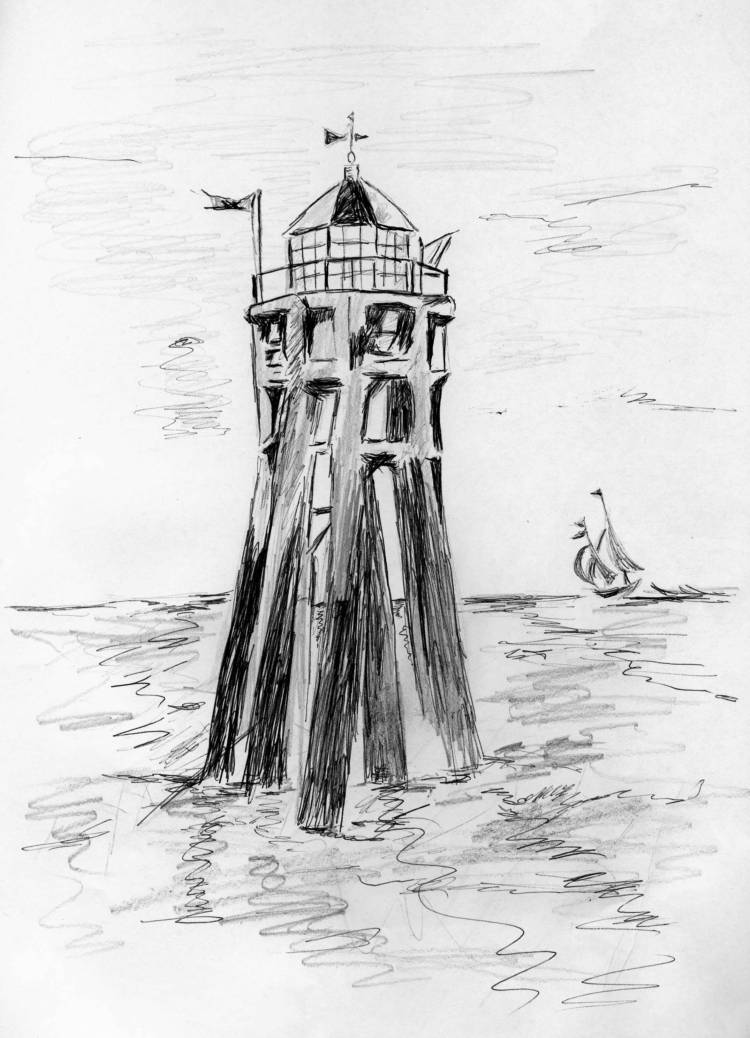

One of the two most fascinating tales is that of the unfortunate lighthouse keepers of Smalls Lighthouse, on a tiny rocky island 20 miles west of Wales. Though the Smalls Lighthouse exists today in a modern, well constructed 19th century design, back when the first lighthouse was built in 1775, it was constructed with strong oak legs that allowed the terrible stormy waves to wash right through and around the legs as the lighthouse keepers sat atop a small hut that swayed precariously in the storms.

Traditionally in British lighthouses, there were always two men at their post for the long shifts spent in splendid isolation. In 1801, the two-man team of Thomas Howell and Thomas Griffith were stationed on Smalls Lighthouse.

Mr. Griffith complained of being unwell, and though his colleague tried his best to help him, it was no use and so a distress signal was set up to try and get the attention of passing ships. Sadly, no help came and after several weeks of extreme suffering, poor Griffiths breathed his last.

For a while, Thomas Howell kept the body of is colleague inside the living compartment with him but understandably after a time this began to bother him, particularly so when the body began to decompose.

Unfortunately, the two men were known to argue quite a lot and Howell’s naturally worried that if he merely threw the body into the sea that he would soon be accused of a treacherous murder.

As luck would have it, Howell had been a Cooper in his younger days and this allowed him to make a coffin for his dead companion, out of boards obtained from a bulkhead in the dwelling apartment. With a great deal of effort and hard work, Howell not only placed the decomposing body in the coffin but then dragged it outside and secured it to the outside railings just outside the windows of the compartment.

The bad weather did not abate and further terrible winds blasted the coffin apart, sending the timbers crashing into the sea. There remained, though, tied to the railings, the emaciated remains of Thomas Griffith. When the winds blew at a particular angle, it appeared that the dead man was beckoning to his colleague.

For four months it was impossible to land on the rocky island and all that could be seen was some sort of distress signal. At the time, though the Royal Navy had its famous custom of communicating with flags, there was no Morse-code or equivalent for Lighthouses or anyone else for that matter. A distress signal could be created but who could know what was being signalled.

Vessels with strong boats and hardy crews were sent to the locality to try, if possible, to land, or if unable to land, to get within hailing distance, and learn the nature of the disaster. They could only get near enough to see the dim outline of one of the men standing on the gallery of the Light-house. Whether he spoke, they could not tell. They would return to their harbour; but the bearers of no intelligence! Again and again would the same attempt be made, and unfortunately with the same result.

Despite all these storms and terrible traumas, Thomas Howell kept the lighthouse lamp lit but it took several more months before a craft was able to land on the island and for all that time, Howell had no choice but to spend every day and night looking out at the beckoning corpse. Not that, people didn’t try to land earlier. Some of the bravest crews of the West Coast attempted landfall but the seas were also too rough. They could see a figure standing on top of the lighthouse waving to them but he never seemed to respond to their shouts and so the sailors were forced to return to port with no more information than they had before.

Of course, something was up, the distress signal had been on for weeks but the lighthouse beacon was lit every night, so nothing could be too bad… could it?

When Howell was finally relieved from the lighthouse the effect the situation had had on him was said to be so extreme that he was driven quite mad and his physical appearance and mental wellbeing had so changed that his friends on the mainland no longer recognised him.

The policy for crewing lighthouses immediately changed and until they were automated in recent years, lighthouses were always staffed with three people, lest any poor individual had to endure four months of anguish on their own, next to their dead companion.

Incidentally, in 2016 a wonderfully gripping film was made about these awful events. The Lighthouse is a terrific film which if in the UK you might find on BBC IPlayer or if not then I recommend a quick visit to Amazon or your local store. Some of the cast and crew were kind enough to like this blog post on Twitter so a link to their great film is the least I can do.

Reblogged this on Pete's Favourite Things and commented:

A tragic but fascinating tale

LikeLike

If it was known beforehand that these two men didn’t get along with each other then how did they ever get stuck together to begin with???

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a really good question!

LikeLike

The wonders of uncaring company bureaucracy, I reckon.

LikeLike

Absolutely fascinating and tragic film, wonderful actors – goosepimples guaranteed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good story but what is the name of that film?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s just called ‘The Lighthouse’

LikeLike

My wife and I watched the movie. It was insane how they got stuck out there. Brave men. I didn’t know one was previously Ill. Unless they are talking mentally, that fact wasn’t in the movie. Otherwise I’d recommend this movie to anyone.

LikeLike

Which Lighthouse did you watch? There are two different films called The Lighthouse. The one the article refers to came out in 2016, but there’s a new one that just hit theaters.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This review is for the old 2016 version.

LikeLike

I have just this evening watched the film, “The Lighthouse,” very gripping indeed. The film seems consistent with your summary of the historical events. Who knows the full range of mental torment Thomas Howell endured.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed the film. I found it equally gripping too even though I already knew the historical events. It’s hard to imagine a more terrible situation than to be trapped on a lighthouse seemingly without ever any hope of rescue with a dead body like that. It must have been unspeakably dreadful for him.

LikeLike

Just watched the film. It was brilliant.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now watching the film and took a quick detour here to check out the historical account. Terrible how a tragedy was always required before safety changes were made. No Risk assessments back then!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My wife and I have just watched the film ‘The Lighthouse’, with its sombre lighting and story line, and we were so moved that we took to looking up some of the historic details of the events depicted in it. What ever happened to the official lighthouse logbook; is it still available to view?

LikeLike

Poor Thomas Howell he must have been terrified he would get the blame

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, what an awful situation to be in… especially back then with capital punishment.

LikeLike