Of all the posts I have written in the last year or so, one of the most popular has been on The Black Death or The Plague as it is known.

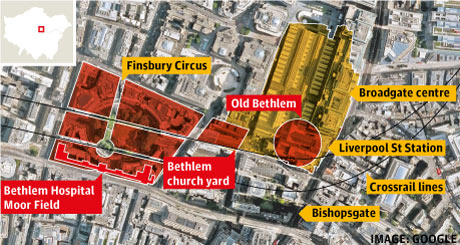

This week it was revealed the archaeological work continues right beneath the streets of one of the busiest parts of London with the graves of over 4,000 people being discovered. Many of these are thought to be victims of The Plague with some of them from the legendary and terrifying Bedlam mental asylum, the very word Bedlam in Britain is still used centuries later to describe madness, insanity and chaos.

As luck would have it, earlier this week I spent three days in the county of Derbyshire. Situated in central England it is not somewhere I have been before though I had long heard of its natural beauty and magnificent country houses. It is those houses that I expected to write about today but as it happened I ended up also visiting a place by chance that I had earlier written about, the village of Eyam.

Eyam is located in The Peak District and an official area of natural beauty. It is quite a long way from anywhere of any importance and the road to the village winds its way through a canyon with cliff faces at least 100 feet tall.

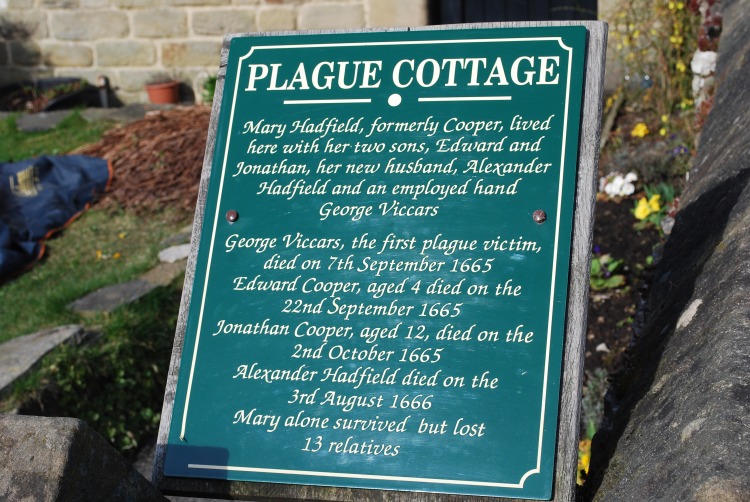

Eyam is famous even today for the events that unfolded there when the Plague hit England in 1665. In the late summer, a tailor by the name of George Viccars. He had travelled back from London where the plague had been raging some 175 miles south and the cloth had become damp on his long journey north. It was common practice to bring materials from London, their throw-away materials when sent to the country would be full of new patterns and designs.

George decided to lodge at the house of Mary Hadfield near Eyams Church and he hung his damp clothes on a line in front of fire. It seems that the heat from the fire woke up the dormant virus on the clothes and soon George fell sick before dying on September 7th 1665.

Very quickly, the plague took the lives of the sons of Mary, the neighbouring Thorpe family, Peter Hawksworth who was another neighbour as well as the Wragg and Sydall families across the road.

The villagers began to panic, it was rare for them to travel more than a few miles from their home and yet they were already aware of the terror of the plague. The isolation of the village had kept it safe but only for so long. Obviously the only explanation was that this was a plague sent by God only this one could kill everyone and not just the eldest Egyptian sons as was the case with Moses.

In 1664 a new young rector had arrived in Eyam and his name was William Mompesson. William Mompesson is central to the events at Eyam and in the midst of the terror decided he would do what he could practically speaking as well as leading his people in prayers to God.

Church services were held on a field, a wise step to limit close public proximity and the chance for the unknown carriers of the plague, fleas to jump from person to person. Plague victims were buried either in their own gardens or crofts (fields).

Mompesson imposed a voluntary exclusion zone on the village of Eyam with no-one being allowed in or out. This was an act of tremendous self-sacrifice as any single individual had a much greater chance of survival if they fled and remained in isolation. However inevitably some of these would carry the plague onwards to other isolated communities or even worse the city of Sheffield.

A lookout was stationed on the road leading to the village from 9pm until 6am. This “watch and ward” would stop any unwitting visitors entering the doomed village or anyone leaving it too.

Mompesson’s Well, a natural spring, was used during the plague as a boundary point in which provisions were left for the village. The wealthy family from nearby Chatsworth Hall gave the villagers lots of assistance in contrast to the Bradshaw family who lived in the village manor house and fled at the first sign of trouble. Money and belongings were left in vinegar in an attempt to stop the unknown elements that spread the plague.

The vast majority of the village died, almost 300 people. William Mompesson had begged his wife to flee with his children as soon as the first person had become ill. However she refused, sending the children away whilst she stayed with her husband. One evening William went for a walk with his wife Kathleen and his heart sank when his wife remarked on how sweet the air smelt. Unknown to her but known to William, the sensation of the air smelling sweet was the earliest sign of suffering from The Black Death. Sadly, Kathleen Mompesson died a few days later and is the only plague victim to buried in the church grave yard. In fact so many people died, there was no longer anyone left to inscribe words on gravestones so most were marked by a simple boulder with a roughly shaped cross carved quickly by family members.

By mid October 1666, the plague in the village had burned itself out. There was simply not enough people left for the plague to sustain itself. Interestingly several people did survive who had close contact with the plague sufferers and the dead including William Mompesson, Mary Hadfield whose home was where George Viccars had stayed despite her family and all her neighbours dying and also the village grave-digger, Marshall Howe. It is thought that these people had a certain level of immunity in their bloodstream.

We spent several hours at beautiful Eyam, firstly visiting the new manor house which was built shortly after The Plague, no doubt as the land was so cheap. It was a large house by normal standards but very small by the standards of most country estates and unusually was still lived in daily by the family until February 2013.

Eyam itself is a very pretty little village full of small period cottages many of which have signs on their walls and plaques in the garden informing of whom and how many people died in each house. It is said that people who live in Eyam talk of the plague as if it happened only yesterday and visiting there it certainly feels very real.

At the centre of the village is the Church of Saint Lawrence which has in its grave yard an 8th century Anglo-Saxon Cross, showing some of its long history that goes back well before the Romans came here for the mining.

The church receives over 100,000 visitors a year and yet keeps its function as a place of worship. Sadly, photos are not allowed inside this church which is a shame as the stained glass windows were wonderfully coloured and the sunshine outside made the church inside glow with warmth. As we read the information boards in the church, everyone fell silent such were terrible events that we read about. It is hard to feel genuinely sorry for people of centuries ago but here I think everyone did as we read their names and the what happened to them.

In the middle of our little holiday we found ourselves saddened and quiet for some time until we went back outside to see the picturesque houses and beautiful scenery.

When the first visitors to Eyam arrived after the plague, they found it an almost deserted place. The roads had all but disappeared and been replaced by grass and weeds. Gardens were overgrown, the fields were empty of crops and the nearby mines which provided employment for 2 millenia were silent. Most of the animals starved to death as the farmers were no longer able to care for their livestock even if they were alive.

It really must have felt like the end of the world whether in busy London or quiet Eyam, totally incomprehensible to all but the most educated of people who even then were powerless to stop it. The dreadful nature of a plague death helps shed light on the horror faced by Eyam’s villagers who agreed to live alongside the plague. Both the bubonic and pneumonic strands of the plague flourished during the Great Plague. The bubonic caused vomiting, a high fever and extreme pains in the limbs. Buboes (swellings) also formed on the lymph glands, sometimes growing to the size of an egg, and eventually bursting.

Daniel Defoe in ‘A Journal of the Plague Year’ advised draining the plague from the victims; the buboes were often cut open or burned: “The Pain of the Swelling was in particular very violent, and to some intolerable; the Physicians and Surgeons may be said to have tortured many poor Creatures, even to Death.” The pneumonic plague ran through the blood, producing extreme fluctuations in the body’s temperature, often resulting in a coma.

Because religion was at the centre of 17th Century English village life, there was a great belief the plague was a punishment for sin. Thus people sought divine forgiveness through prayer and repentance in the hope they would be spared. Its causes and cures unknown, a variety of medical treatments were tried. Many believed bad air created mass infection and therefore when windows were closed, rosemary and incense were burned to ventilate homes, whilst fires roared in the streets in the vain hope of clearing the infected air.

One man, Andrew Merrill went to live in the field behind his house making a small shed out of wood and living there for over a year with just a cockerel for company. Anyone who doesn’t know how cold and snowy the area is in winter can guess by its name The Peak District.

One lady broke the quarantine and tried to go to the market at nearby Tideswell to get supplies but was forced to flee for her life when she was recognised and people shouted “A woman from Eyam, The Plague!” before throwing objects at her.

On another occasion a man from the wealthy Chatsworth Estate travelled by himself to Eyam in the rain with a cart carrying wood. He had to unload the wood by himself in the cold and returned home and became unwell and people thought he must have the plague. His neighbours told him they would shoot him if he left his house. The Earl of Devonshire whose descendants still live at Chatsworth sent for a doctor. The doctor was so scared that he examined the man from the other side of a broad river. Eventually it was decided that the poor man simply had a bad cold from working out in the rain for so long.

It all must have been similar to surviving a nuclear holocaust but now the village is rather paradisical place now albeit overshadowed by the terrible events of times past.

The whole village is now maintained by The National Trust and is a thriving rural and tourist village, well worth visiting if you’re in the area or to make a weekend of it like I did if staying in London. Words and pictures can’t quite say what it is like there now, let alone then, the best thing to do is visit it yourself. Be grateful of living in an era of modern medicine and say a prayer for the millions of ancestors killed by the plague sent from hell and sparing a thought for the frightened but brave villagers of Eyam who sacrificed themselves in the hope of saving others that they did not know.

Thanks for this interesting post. Reading your descriptions and seeing the photos brought the place alive. Years ago, I stayed up late reading A Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks. It is novel based on this event, and I read it with tears streaming down my face.

LikeLike

Thank-you for your comments. I am glad that you enjoyed it. On your recommendation 🙂 I have ordered A Year of Wonders.

LikeLike

I hope you enjoy it! 🙂

LikeLike

I love this blog. Teaching me more about my own country’s history than I was ever taught at school. Fascinating stuff about Eyam – will have to try to visit there one day.

LikeLike

Thank-you! I am much the same, I learnt next to nothing of history at school but somehow enjoyed it myself so went to study it at Uni.

Eyam is well worth the visit and the surrounding countryside is really great. With Chatsworth House, Bolsover Castle, Hardwick Hall and all the places in the National Park like Matlock, I will have to go back too!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this post. I visited Eyam a number of years ago, arriving at night to stay at a hotel, we had to duck to get through the doorway. Wandering the village in the evening I could not make myself walk across the threshold of the cemetery … I just couldn’t do it, something strong kept me out. Sounds weird but in the daylight, I was happy to wander thru reading, astounded at the history of the little village. Having read The Year of Wonders my friend and I were drawn here to discover for ourselves. Well worth the visit!

LikeLike

I’m glad you liked it. I can totally relate to your experience at Eyam. It’s almost like it happened yesterday.

I think the fact the buildings are all made of stone and apart from tarmac roads and cars there are hardly any signs of even the 19th century let alone the 21st century.

Its amazing to think that the houses we look at are the very same as the what the people lived in back then.

I can’t wait to received my copy of The Year of Wonders. One of the nice things about blogging is that you get lots of little tips from other people 🙂

LikeLike

Wonderful post – truly hard to imagine what they suffered.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on digger666.

LikeLike

Great post! I should really visit Eyam at some point next time I’m abroad. Defoe is probably the most well-known writer about the plague but he was also probably a child when the major epidemics hit; you should really read Thomas Dekker’s “The Wonderful Year” if you haven’t yet. It’s a pamphlet rather than a book– he actually has a few which address the plague but that one’s the best one to start with.

Keep on posting!

LikeLike

Very interesting account.

LikeLike

i visited Eyam some years back and, travelling on foot, was stopped at the entrance to the town by the ‘watch’ you mentioned, declaring that Eyam was a plague town. The pastor of the lovely church there took me to the bell-ringing practice and explained the history of the town, including the Vinegar Stone, a huge boulder on the edge of town with holes drilled in it so that people from the next village who brought food could collect their coins, duly sanitized in vinegar.

Strange to say, a WHO report brought out recently describes the people of Eyam as being the most resistant to both strains of the black death to this day. Their ancestor’s sacrifice remains admired throughout England as being unusually sane and level-headed for the time.

LikeLike

Thank-you for your comment. It sounds like you had an extra special visit to Eyam. Yes I read the WHO report yesterday with them have a 15% resistance in their genetic makeup. I guess from their ancestors who came into contact with the disease but survived.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing your holiday with us. I’ve heard of this village and the sacrifices they made but had never seen pictures of it. Eyam is now on my list of places to visit when I come to England.

LikeLike

I have nominated you for the Versatile Blogger Award. Should you accept, please follow the link below. I enjoy visiting this blog and reading your work. Thank you and well done.

LikeLike

I remember visiting Eyam with school when I was about 9 years old. The story stuck with me ever since. I’ve just stumbled across your blog, will certainly be coming back to read some more of your posts

LikeLike

I go to Eyam a lot. I always get the 65 Sheffield to Buxton bus and it stops in Eyam Square. It is a small quiet village that made a huge heroic self sacrifice. They saw their death coming but they stood their ground. Eyam is a very special place. It makes me feel sad to think about what happened in 1665 and 1666. They stood their ground in the face of death. These people will be remembered and honoured for generations. I hope that they are resting in peace now. They should be in Heaven now watching down on everyone who respects and rewembers what they did. REST IN PEACE PEOPLE OF EYAM 1665 TO 1666.

LikeLike

Heard about this village as a schoolgirl, I visited it for the first time in 2019.

It is such an atmospheric place, and I will always see what they did as the greatest self sacrifice in human history.

LikeLike

I feel so sorry for the people that died of the plague. It must of been really bad. I can’t even begin to imagine the pain and horror they must of felt. I really wish there was a way to remember all those that died of the plague. This includes the beginning plague and the end of the plague

I don’t really understand why I feel so sorry to them. It was before my time and I shouldn’t but I do. It’s sad and I really feel for them.

LikeLike

I know how you feel. Last year, I visited and had the honour of meeting one of their descendants.

I thanked them through him for their courage and unselfishness, because many of us wouldn’t be here if not for them.

LikeLike

i have visited eyam a few times when i was a child. my dad has a Phd, and so our family outings often related to history in some way. anyhow, i was so intrigued by the plague, that i made a folder with all the names, dates and ages of everybody who died of the plague, the story behind how it arrived in eyam, and even a brief mention of emmot sydall. she was a young girl from eyam, who was betrothed to a boy called rowland i believe, who lived in the next village (stoney middleton). when the plague came they would meet on the boundary to eyam, but seperate themselves by the stream. anyhow, these meetings continued in secret right through until april 1666. when emmott stopped appearing. when the village was released from its quarantine, rowland was one of the first visitors to eyam, he came searching for emmot in the hope they could marry.

unfortunately, along with several members of her family, emmot died at the hands of the plague in april 1666. i always found it so touching. i am a young women now, engaged , preparing for marriage, and i can only imagine how awful it must have been to have been separated before their lives together could really start…

i remember this sad poem, and often think of emmot and rowland

as the young olive, in some sylvan scene,

crown’d by fresh fountains, with eternal green,

lifts the gay head, in snowy flowrets fair,

and plays and dances to the gentle air

when lo! a whirlwind from high heaven invades,

the tender plant and whithers all its shades,

it lies uprooted, from its genial bed

a lovely ruin

now defaced, and dead!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, can I just say that the whole village is not maintained by the National Trust, just Eyam Hall and Riley Graves. Thanks.

LikeLike